Behind the story: Sailing to a steel behemoth worthy of Melville

“The Crystal Ship” is about to set sail.

When I first heard the rumor that Platform Holly, one of nearly two dozen oil platforms in the Santa Barbara Channel, had inspired the signature image for the Doors’ dirge to lost love, I was skeptical.

Drilling platforms are nothing especially poetic. By day, they are dark specks on the horizon, ships going nowhere. But at twilight, when their lights begin to glow beneath the dimming sky, they sparkle like diadems in the inky black lying somewhere between the mainland and the distant islands.

Perhaps Jim Morrison was right.

I have been peering out at these structures for nearly half a century from the beach at Carpinteria, the wharf at Santa Barbara and U.S. 101 as it scoots high above the surf line. Their presence on the coast feels as intrinsic to the landscape of California as the Golden Gate Bridge or sprawl of Los Angeles, and as much as some would like to see them disappear, their absence will hardly solve our insatiable appetite for fossil fuels.

A historic oil platform off Santa Barbara turns into a rusty ghost ship »

So when the Trump administration announced plans to expand leasing on the coast for oil and gas development, I wanted to visit one of these platforms. A reporter from The Times had done this before, and when I learned that three of the platforms had been shut down — “decommissioned” is the formal word — the story became more interesting. (Since I started reporting, four more platforms were scheduled to go.)

I reached out to the operators. Chevron, which managed Platforms Grace and Gail, said no.

We received your inquiry and wanted to let you know we will not be participating in this opportunity. We appreciate your interest in Chevron.

I reached out to Beacon West, the company working at Platform Holly. Its president similarly declined.

I think it would be a good story, but unfortunately I am not going to be able to help you out with this. Good luck.

I had been told that because of The Times’ editorials against offshore drilling, oil companies would be reluctant to give me access to the platforms. But I saw a possible opening with the State Lands Commission, which is managing the decommissioning of Platform Holly because it is located in state, not federal, waters.

More than 20 years have passed since a platform in the channel was decommissioned. In the spring of 1996, Chevron abandoned four rigs off Carpinteria — undersea explosions severed their legs, and the hulking structures were cut into pieces, lifted onto a barge and floated away.

Their dismantling left political writer Lou Cannon saddened by the loss. The twinkling lights of one, Hilda, were “most comforting during the holiday season,” he wrote, “when days are short and the platform’s Christmas lights would shine merrily through the winter darkness.”

Such sentimentality is rare and perhaps a little misplaced. When I wrote the State Lands Commission, I explained that I was less interested in politics than in the lives of the workers who would be leaving Holly behind. A little more than a month later, I stood on the deck of the crew boat approaching this steel behemoth, a structure worthy of Melville, and as a writer, I was thrilled.

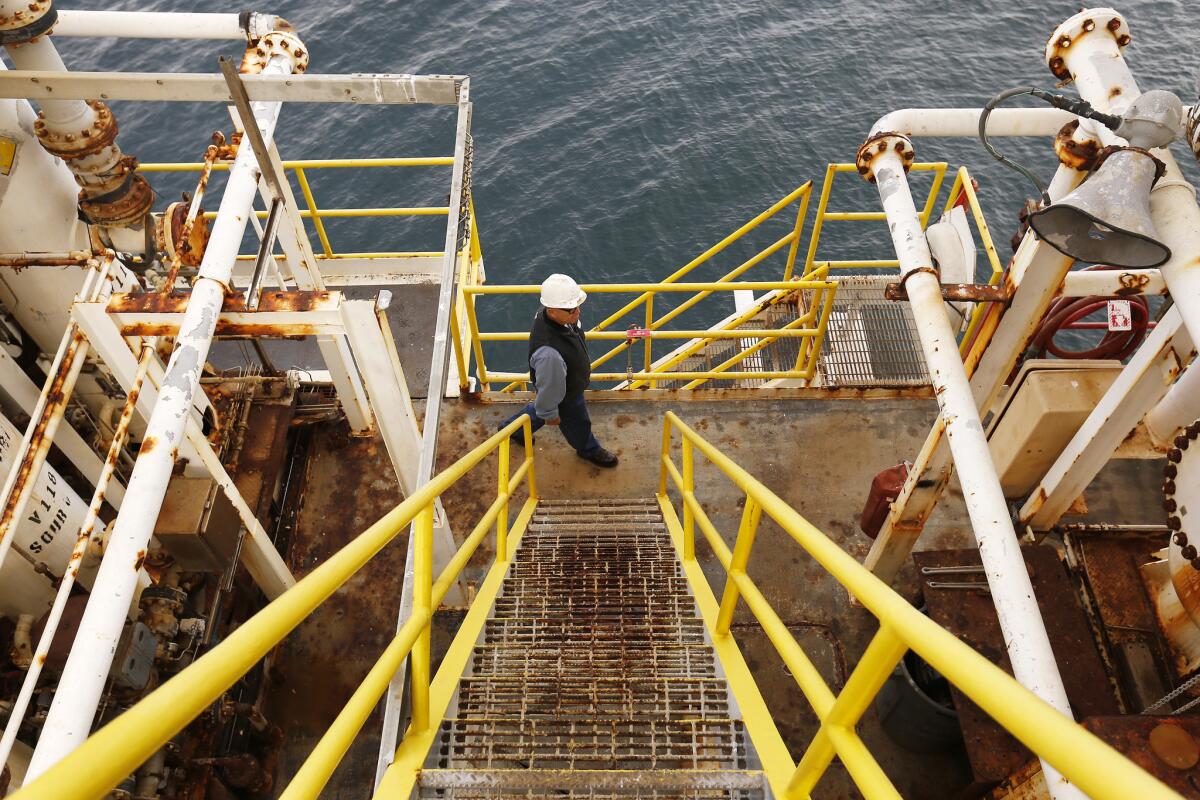

I had taken the prerequisite safety class, learned about the dangers of hydrogen sulfide, practiced the rope swing for jumping between ship and platform, and donned fire-resistant coveralls and hard hat.

The crew boat took off from a pier just north of the Sandpiper Golf Course and the Ritz-Carlton Bacara, a resort that suggests what the future of the coast might look like in the absence of Holly and its onshore processing facility. More than 70 years ago, the site was targeted and shelled by a Japanese submarine that had taken aim at an aviation fuel tank.

Together with Times photographers Katie Falkenberg and Al Seib and Times graphics journalist Priya Krishnakumar, I swung my way on board and climbed the stairs that zigzagged over the surging sea below. We spent almost three hours walking in the footsteps of the former operators of the platform, lingering with their ghosts on the catwalks and in the control booths.

Wandering Holly is like walking through a closed-down steel mill. This is our Rust Belt, I thought: a factory set high above the broad Pacific. The juxtaposition is as incongruous as it is hazardous. Fifty years ago, a blowout on another platform led to one of California’s greatest environmental disasters.

The maze of pipes and tanks, squeezed into the platform, reminded me of the artwork of Piranesi with his elaborate architectural drawings. I felt as if I had dropped back in time with the analog switches, dials and gauges. The equipment had been modernized, but vestiges of the past remained, as alien as the underground bunker the survivors of “Lost” discovered.

Unlike platforms farther out at sea, no one slept onboard Holly. The crew boat ferried workers back and forth twice a day — seven days on, seven days off — but they prepared meals here. In the galley, we found a spice rack with Cajun seasoning and curry powder, a refrigerator filled with fish sticks and veggies, a rotary phone and a clock stuck at 4:46.

On the drill deck, we stepped inside a doghouse where someone had scribbled a record of the day’s progress. The floor was littered with tattered sheets of paper, an hour-by-hour chronology of their work probing deep beneath Earth’s surface. I picked up one; it was dated June 24, 2014.

And we stood 35 feet above the sea that glimmered in the afternoon light like diamonds. I imagined what it was like to work here through the seasons, watching the migration of whales, clouds darkening the horizon in winter, the countless sunrises and sunsets. During the Northridge earthquake, we were told, the platform shook like a dog, and one worker recalled the whole coastline going dark in the aftermath.

Nostalgia may not be the politically correct response to the loss of this crystal ship. But for the workers who spent their lives on Platform Holly and await its inevitable demise, nostalgia might soon be all that’s left.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.