Appreciation: Why Jessye Norman was more than a great voice. Much more

Shortly after 9/11, Jessye Norman was scheduled to sing Schubert’s solemn song cycle “Die Winterreisse” (Winter’s Journey) staged by Robert Wilson in Paris. She called the director first thing in the morning and said she had been crying all night, overcome with emotion about the terrorist attacks, and she couldn’t possibly perform that night.

“But Jessye,” Wilson told her, “that’s why you have to sing. We need to hear your voice.”

She did sing. And sure enough, during a sad song, she started to cry, Wilson recounted on the phone Tuesday from Düsseldorf, Germany, where he is rehearsing. “Tears ran down her face, and she stopped and just stood. Not singing, not moving, just standing.

“I don’t know anyone who could have done that. What she was feeling was so deep in just standing there that it moved the entire audience to tears,” Wilson continued, his voice breaking. “For 10 minutes! For 10 minutes!

“Her silence could be even more moving and more powerful than her singing.”

That’s saying a lot, because Norman, who died Monday at age 74, had a voice that, in her prime, filled any room or arena with a glorious sound capable of taking over your psyche. She had a presence that could hypnotize an audience.

I once told her that I wished she would run for president. She was smart. She devoted her life not just to her voice but to using her voice to make the world a better place. She was the most dedicated superstar in opera. She was articulate and measured her every word. Most of all, she could make you vote for her. She had that kind of command.

She laughed at the suggestion. She had huge, magnetic eyes that then seemed to turn in their sockets. “Hmmm,” she said. More laughter. But the amazing thing is that even in that laughter, there was stillness. I had never seen anyone who could be so inside her own body and make that so meaningful.

As we look back on the career of one of America’s most celebrated opera stars — forget opera, she was a transformative artist, plain and simple — the 10 silent Paris moments are worthy of entering opera lore, as they are of finding room in the annals of 9/11. What they represent, as only Norman (or Miss Norman as even some of her closest friends addressed her, ever in awe) could, is the capacity of art to make us go so deeply inside our emotions that we overcome them and have a new awareness, a mini enlightenment. The first sound you hear after that silence will resonate with a natural wonder that connects you to your environment and maybe will even make you feel whole again.

Yes, she made stock operatic characters come startlingly to life. Yes, she brought an intensity to Strauss’ “Four Last Songs,” to Isolde’s “Liebestod,” to Mahler’s “Song of the Earth,” all that end-of-days music that treads the line between life and death.

Yes, she got all the honors, the Grammys, the medals, the awards that the world has to give artists. She sang for five presidents. Jimmy Carter, who turned 95 the day after she died, had made Norman promise to sing at his funeral.

And, yes, you can read her memoirs, hear her interviews, listen to her recordings and get a pretty good idea of the exceptional care with which she managed her voice, her art and her life. That’s all knowable. But Norman, herself, is far less knowable.

“Art makes each of us whole by insisting that we use all of our senses, our heads and our hearts, that we express with our bodies, our voices, our hands, as well as our minds.”

— Jessye Norman

Wilson seems to be a too-little-acknowledged key player in her development. So too, Southern California, which proved fertile ground for the Georgia-born Norman to grow as a singer. She made her debut at the Hollywood Bowl’s 50th anniversary concert in 1972, an unknown starring in a gala concert performance of “Aida” with a young James Levine conducting. She was back in town at the Bowl or with the Los Angeles Philharmonic or in recital every season for the rest of the decade. In 1974 she toured with Zubin Mehta and the L.A. Phil.

She didn’t make all that much of an impression in these pages, however. Repeated appearances got increasingly less play and were assigned to freelance reviewers. She was considered to have a very large voice but one lacking personality and, well, not always in control — magnificent if ungainly.

Her reputation grew, and in 1983, Norman made her Metropolitan Opera debut as Dido in Berlioz’s “Les Troyens.” Martin Bernheimer, The Times music critic who died Sunday, wrote in his not-altogether-gallant way that he was impressed. “She proved,” he said, “that histrionic restraint and expressive intensity can do much to counteract the romantic disadvantage of a decidedly ample physique.”

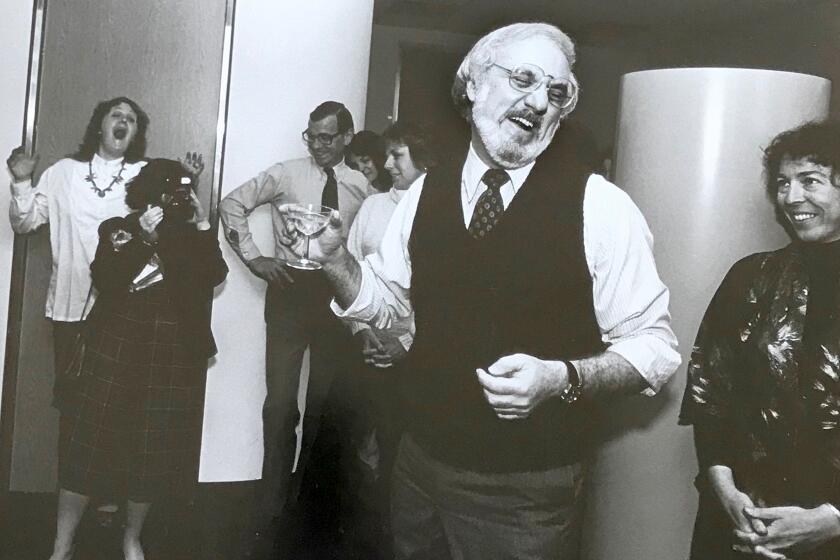

In point of fact, she was, by this point, incomparable. Something had happened to her, and that something came the year before, while she was working for the first time with Wilson in a staged production of spirituals called “Great Day in the Morning” in Paris. In that production she found her focus, her bearing, her being. She was groomed to be, if not president, at least queen. The next year she would have appeared with David Bowie in the eight-hour mega-opera “the CIVIL warS” that Wilson had devised for the L.A. Olympic Arts Festival had the funding been raised.

“Amazing Grace” was the final song. Norman wrote in her memoir, “Stand Up Straight and Sing!”: “Under Bob Wilson’s direction, I sang this unaccompanied while pouring, over the course of a full four minutes, a pitcher of water, lighted from above and below, onto a Lucite table, the water and light flowing seamlessly from pitcher to tabletop to floor, the audience becoming a part of that continuous stream. We had, in the end, become one.”

She leaves it at that and says little more about Wilson, although she does mention that she had become interested in India and Hindu thought. I always figured this was the moment of great transformation when Jessye Norman became Jessye Norman.

Love him or hate him, the L.A. Times’ feared and funny Pulitzer-winning music critic Martin Bernheimer was a law unto himself for three decades.

Wilson denies that he had all that much to do with it. He told me he simply saw in her what the rest of us missed. He helped give her a little more confidence and demonstrated how she might move more slowly and smoothly.

“She had nobility in just sitting or standing,” Wilson explained. “When I first met her in the early ’70s, I just couldn’t take my eyes off her. She was so beautiful sitting, and when she stood it was as beautiful as when she sang.”

All he claims to have done is brought that out for others to see. “She always understood her body,” he said.

To prove his point about Norman’s ingrained authority, Wilson described an incident when he first got to know her. After attending an opera performance in Amsterdam, they encountered the police attacking a black man on the street. Norman asked what was going on.

“The police said it was none of your business,” Wilson recounted, “and she said, ‘It is my business.’ We went to the police station with the man and waited all night long. She refused to leave until they released him.”

Rachael Worby, the artistic director of the Pasadena ensemble Muse/ique and Norman’s regular conductor on tours and special projects over the last 15 years, expressed much the same thing. “They may call her a diva,” Worby said, “but everything she did was really at the service of raising people up. She gravitated towards people, such as Henry Louis Gates Jr., Gloria Steinem and Maya Angelou, people whose life work is to deal with chaos.”

Worby also sent me an email with a quote Norman gave at a commencement speech that summed up her attitude toward art and society. “Art makes each of us whole,” Norman concluded, “by insisting that we use all of our senses, our heads and our hearts, that we express with our bodies, our voices, our hands, as well as our minds.”

The Los Angeles Philharmonic elevates its chief operating officer to replace Simon Woods and to fill big shoes left behind by Deborah Borda.

One of Norman’s last projects was one of her most unexpected, appearing in a San Francisco Symphony performance of John Cage’s “Song Books,” with avant-garde singers Meredith Monk and Joan La Barbara. Michael Tilson Thomas, a longtime Norman friend and the only one who could conceive of such a trio, conducted. Yuval Sharon directed.

Sharon said he was terrified asking this legend, so grand, to do things like sit at a typewriter and do nothing. “But it was so moving,” he said, “to see her strip away the veneer and just give herself completely to the material.

“She had to unlearn being herself and just be present. But she, in fact, had a quiet obedience about the project.”

Having bonded with Monk, Norman had even hoped to attend one of the L.A. Phil performances of Monk’s opera, “Atlas,” that Sharon directed in June. By then Norman, who was using a wheelchair and in great pain, was unable to travel. But it’s nice to think that she was there in spirit, since this would have made a lovely closing of the circle that began with “Aida” and the L.A. Phil at the Bowl 47 years earlier.

Jessye Norman will not be forgotten. And “Great Day in the Morning” should not be either. It was recorded, yet her supposedly loyal label, Philips, released it only as an LP in France and never made it available on CD or download. It may be her greatest recording and belongs on any list of the world’s greatest recordings. The “Winterreise” was broadcast on European television. That’s nowhere to be found either. Nor have any of her many astonishing recordings been remastered in high resolution sound, not that any resolution is high enough to capture her essence. Still, she deserves better.

This fall’s classical music highlights include Esa-Pekka Salonen, “Porgy and Bess” and the L.A. Phil’s birthday gala.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.