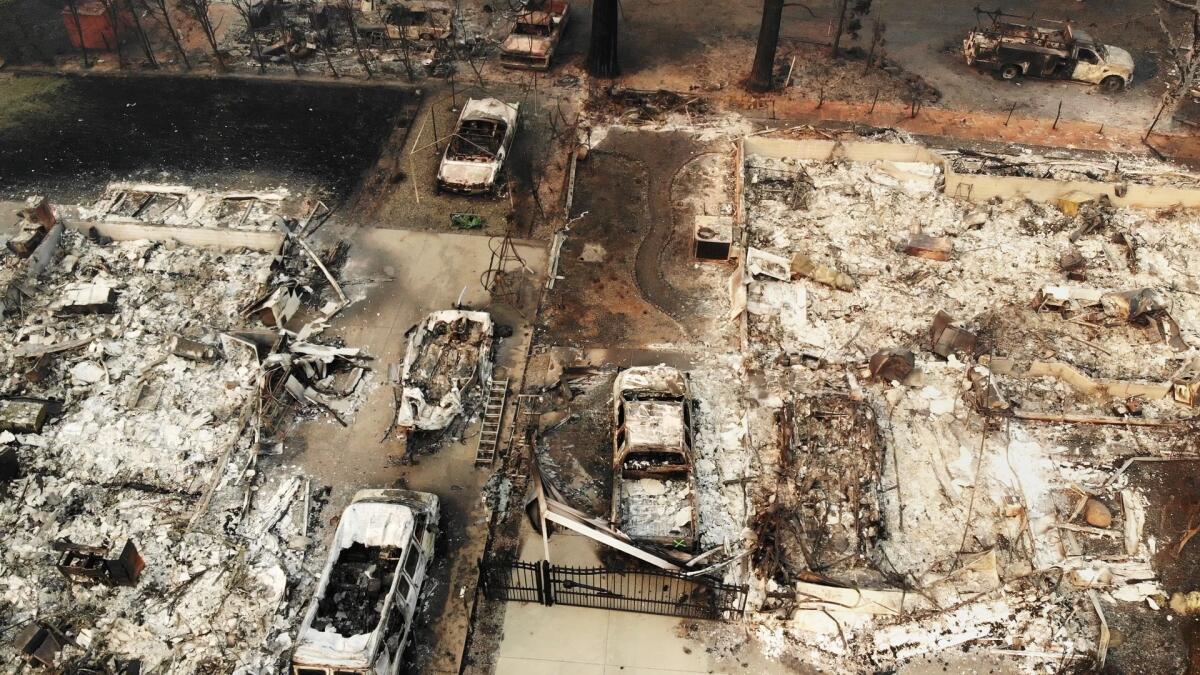

Left behind by the Camp fire: Up to 8 million tons of debris

The first job was to contain the state’s deadliest and most destructive wildfire. The second is to deal with what it left behind.

With more than 17,000 structures destroyed by the Camp fire, authorities will soon begin a cleanup that will test their ingenuity like never before: removal of an estimated 6 to 8 million tons of toxic rubble, soil and concrete strewn across 150,000 acres of mountain terrain, an area roughly the size of Chicago.

If all goes according to plan, what is expected to be the most expensive cleanup campaign in state history will be completed within six months to a year, allowing some displaced Paradise residents to begin rebuilding their homes by summer, said Sean Smith, state debris removal coordinator.

“We still have some creative work to do,” Smith said, “but I’m pushing hard to get that debris off the ground in time for people to start rebuilding in optimal weather.”

The project will be managed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, with help from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and state and county authorities, as well as thousands of contract workers.

It will begin in a week or two, Smith said, when certified crews arrive to assess levels of hazardous and carcinogenic materials such as lead, asbestos, pesticides, herbicides and propane tanks on a lot-by-lot basis.

In January, fleets of contracted bulldozers, dump trucks, cranes and track hoes with mechanical jaws at the ends of 30-foot hydraulic arms will swarm the narrow mountain roads of the Sierra foothills city, about 10 miles east of Chico.

Half of the debris — burned concrete and metal including vehicles — will be taken to a railyard in Chico and later transported to a recycling center.

“The debris will be hauled in trucks lined and covered with heavy plastic to ensure containment of the materials while they are in transit” to seven different landfills as far as Kettleman City, about 300 miles to the south, said Bryan May, a spokesman for the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services.

Landfills in the immediate vicinity of Paradise and neighboring mountain communities won’t be burdened by the federal cleanup, leaving them available to those who live in the area, officials said.

The cost of excavating and removing Camp fire debris is expected to far surpass the $1.3 billion spent cleaning up after the Tubbs fire of 2017 in the Santa Rosa area, the second-most destructive wildfire in California history.

That fire destroyed more than 4,600 homes, many of them in the city of Santa Rosa, and produced more than 2 million tons of toxic debris, which overwhelmed regional landfills already brimming with rubble from a series of earlier fires, Smith said.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency will fund 75% of the effort, with the rest paid for by the state Governor’s Office of Emergency Services, officials said.

An estimated 1,500 people a day were registering for disaster assistance at a recovery center jointly operated by the Office of Emergency Services and FEMA in a former Sears store in Chico. As of Thursday, about 18,807 claims had been submitted by Butte County residents for FEMA assistance of some kind, FEMA spokesman Frank Mansell said.

Authorities this week announced that their targeted searches for human remains had ended, leaving the fatality count at 88, with 126 still missing. After a three-week evacuation, some residents are being allowed to return to neighborhoods that escaped the worst of the blaze.

It is yet to be determined when all residents will be allowed to make that grim pilgrimage back to their neighborhoods to examine the destruction for themselves and see if anything is salvageable.

No one can say how many of Paradise’s 26,000 residents — many of them seniors and few of them wealthy — will have the will or the means to start over there.

“We’re leaving the first response mode and transitioning into a long and painful triage phase,” said Ed Mayer, executive officer of the Butte County Housing Authority, gazing out his office window overlooking fire evacuees in a tent city that has sprung up by the Walmart across the street. It involves “new stark realities of tracking down displaced people, sheltering them and making them feel safe.”

“No one knows how many of them will be homeless in six months,” he said.

Smith pointed to the progress made in the rebuilding effort after other fires across the state, including the Thomas fire last winter in Ventura and Santa Barbara counties.

“The Thomas fire broke out around Christmas and residents there were rebuilding by April,” Smith said. “I believe folks will come back to Paradise too.”

The damage left behind is not just on the ground, as federal scientists begin coming to terms with the staggering toll of California’s 2018 fire season on the Earth’s atmosphere.

Wildfires statewide emitted roughly 68 million tons of carbon dioxide, or about 15% of all California emissions, according to a U.S. Geological Survey study released Friday.

The Camp fire, which broke out Nov. 8, and the Woolsey fire, which erupted near Simi Valley the same day, produced emissions equivalent to roughly 5.5 million tons of carbon dioxide, the study found.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.