The two women tried to avert disaster.

Kandince Cuellar told her abusive boyfriend she was going to leave him. He was having terrible headaches and said he wanted to die. She was afraid.

Her best friend, Marlene Lopez, tried to persuade him to go to the emergency room for help; she thought it would keep all of them safe. Maybe tomorrow, he told her.

They hid his handguns, the 9-millimeter and the chrome-plated revolver. But they missed the Remington Wingmaster 12-gauge shotgun tucked away in the garage.

That’s the one Eric Krause grabbed on a chilly November day. The one he used on Cuellar and her lover, Geoff Garland. The one he finally turned on himself.

Chances are, you didn’t hear about the double murder-suicide in Atwater Village, which played out in the early morning darkness on Veterans Day. It happened just days after a gunman shot 12 people to death in a Thousand Oaks country music bar, while raging wildfires scorched the state and midterm elections flipped the U.S. House of Representatives from red to blue.

But news overload is not the only reason the carnage in the small stucco house with a Spanish tile roof escaped widespread notice. It claimed three people who were bound by poverty, addiction and mental illness. Like many in Southern California’s growing population of people who are homeless, and those who are nearly so, they were searching for a place to belong.

They found one — and that was the problem.

This is a crime story. And a love story. It’s a story about life on the porous border between haves and have-nots, between hanging on and losing everything, between home and homeless encampment, between life and death.

Most of all, it’s a story about Los Angeles.

::

The Los Angeles River winds along the western edge of Atwater Village, a leafy neighborhood whose modest Spanish-style houses were built for railyard workers and laborers who staffed the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power substation in the early decades of the 20th century. Today, it’s a rapidly gentrifying area between Glendale and Griffith Park, whose recent home renovations are evidence of its growing affluence.

It began as so many do — while reporting another story. A Times photographer and I were finishing an article about the odd and sometimes ingenious ways that homeless people seek — and find — shelter. Then we heard about a double murder-suicide.

The scruffy, 1,135-square-foot house on Glenmanor Place where Krause and Cuellar lived and died was built in 1924. It sold in April for $710,000, and the new owners quickly tore it down. A modern two-story house and two separate granny flats are rising in its place. Contractor William Bartz said he expects the property to sell for about $1.5 million.

Cuellar and Krause’s former home was also a quick walk to one of the most established homeless encampments in Los Angeles, a place filled with intricate tents and makeshift shelters on small islands in the river.

Some of these jury-rigged homes are powered by generators and solar panels. There are trees for shade and rugs for warmth and dogs for company and a long-standing community of people who either cannot afford to live elsewhere or do not want to leave the freedom of the streets.

The residents of this riverside encampment are among the nearly 59,000 homeless people who live in Los Angeles County, according to the most recent count released in June. That’s a 12% increase from 2018.

Suicide prevention resources

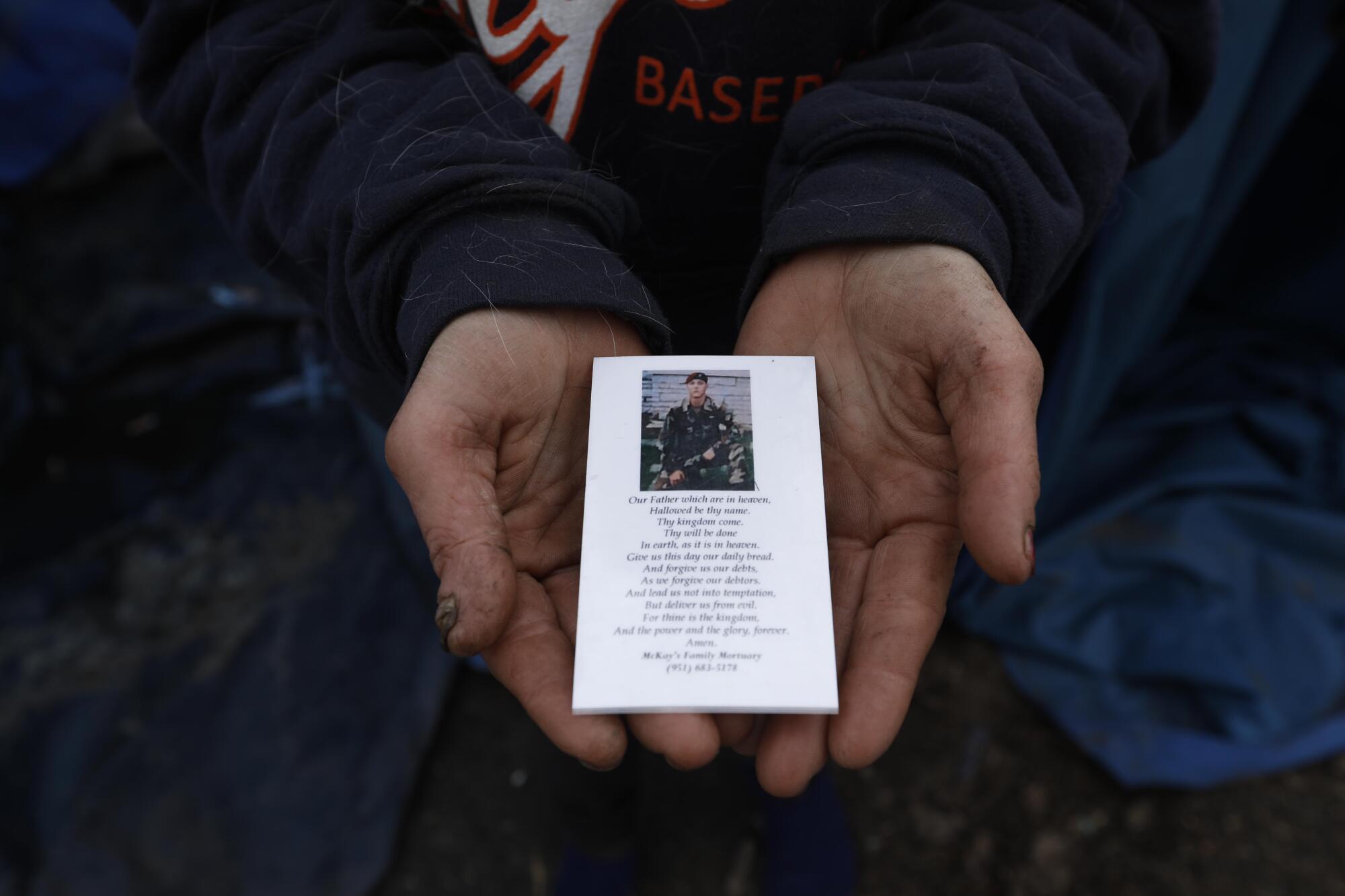

Garland — a hard-partying Army veteran with a string of ex-girlfriends and misdemeanor drug arrests — lived in the encampment for the better part of six years. He died less than a mile away, one of 66 homeless people in Los Angeles County whose deaths in 2018 were ruled homicides.

Garland was felled by a single shotgun blast to the upper right side of his chest, which tore through both lungs and his heart and fractured two ribs.

The autopsy was performed on what would have been his 41st birthday.

Garland grew up in the Antelope Valley. His parents divorced when he was a child, and he began drinking and using methamphetamine as a teenager. But it was his older brother’s death in 1995 that sent him on a downward spiral.

His brother was believed to be either high or drunk when he veered through the center divider of a local road, slammed head-on into a pickup and died. Garland was 17 years old.

“His older brother took care of Geoff,” said Eric Sanders, a friend of the brother. “I think that really sent him sideways.”

Garland served in the Army from November 1998 to August 2001. When he was discharged, he returned to Lancaster and began dating one of his mother’s friends, Mary Hoag, who was 16 years his senior. He moved in with her, and they were together for three years.

But when Hoag caught Garland smoking pot with her teenage son and figured out that he’d been stealing from her, she kicked him out.

Hoag, now 57, remembers how alcohol changed Garland. When he was drinking, he was fun but out of control. “He would start early in the morning,” she said. “I don’t think he was able to fight that demon off. He never really got that help.”

Column One

Column One is a showcase for compelling storytelling from Los Angeles Times.

For the next several years, Garland bounced around the Southwest before returning to Los Angeles in 2008; the last decade of his life was a blur of drugs, alcohol and run-ins with police. He was arrested more than 20 times, mostly for public intoxication or possession of small amounts of drugs.

By 2018 he had begun to think seriously about leaving the streets. But like many chronically homeless people, he found it was a difficult transition. His last address was the L.A. River, where he met Melissa Millner, now 47. He was skateboarding at the time and tried to impress her. Instead, she said, he took a header into the river’s shallow waters.

He picked himself up, dripping wet, and smiled.

“Good impression, huh?” he said.

Garland was funny, Millner recounted, and energetic. He had blue eyes, black hair and flames tattooed on his right calf. They dated for three years, and she was his entree into a community that shared food, shelter and drugs.

“Everyone here does meth,” said Tyrone Hart, 56, who has lived along the river for decades and calls himself Garland’s best friend. “It’s self-medication. Everyone has something that hurts inside.”

::

Eric Paul Krause’s journey to the blood-spattered bedroom on Glenmanor Place included a life-changing motorcycle accident in 2016 on a road in Arizona, which scarred him inside and out.

The accident left him with a deep gouge curving from the middle of his chin up through the edge of his lips, twisting his mouth into a slight but permanent sneer. His autopsy report makes no mention of the prominent scar; the shotgun blast appears to have blown it away along with the left side of his face.

Krause began to wonder out loud how anyone could love him. And he clung to Cuellar in ways that were both fierce and controlling.

“I didn’t like the person she was becoming with him around,” Lopez said, describing her friend as on edge and always fighting with her boyfriend. Krause was “messing with her mind, playing mind games.”

Not long after the accident, Krause and Cuellar moved to California. Krause’s stepfather, Gary L. Williams — a pastor and former real estate investor — had befriended an elderly member of his Southern California congregation named Marshall Freeman.

Freeman had suffered a stroke and was bedridden. He put Williams in charge of his living trust, gave him power of attorney over his financial affairs and deeded his Spanish-style house to the pastor, property records show.

Williams arranged for Krause and Cuellar to move in with Freeman, who was about 70 at the time. A home care aide looked after the elderly man during the day, and the couple was supposed to care for him at night. In return, they lived rent-free in the two-bedroom, two-bath house with hardwood floors and a leafy yard.

Barbara Williams, Krause’s mother, and his stepfather declined to comment for this story.

On its face, it was a good deal. Lopez, a frequent visitor to the Atwater Village home, said Freeman was well cared for, although he did not leave his room. But neighbors said that as soon as the couple moved in, the screaming matches began, strangers started showing up, and the once well-kept yard became filled with trash.

Kim Sze, Freeman’s neighbor of four decades, said “the homeless people were in and out of Marshall’s house like they had found a new haven there. I was like, ‘What the heck is happening?’”

What happened was the lure of the Los Angeles River. Krause and Cuellar would cycle to the well-established homeless encampment, and they became close to many of its residents, including Melissa Dobbs, who came to regard Cuellar as a good friend.

Dobbs said they would hang out in Freeman’s house, cooking meals, doing laundry and partying into the night. Krause gave her free run of the pantry. When there was nothing left, he lent her money for food. The door was always open.

Homeless people often feel invisible to their better-off neighbors, who hurry by on foot or via car, eyes averted. But Monica Alcaraz, who oversees a church shelter program, says that doesn’t mean they’re totally disconnected from the domestic lives of others.

Alcaraz says there’s an elderly man in her Highland Park neighborhood who sometimes lets homeless people crash in his house for the night. “I know that there’s a couple of houses in the area where people go and take a shower there,” she said, “and it’s OK.”

Alcaraz says Krause and Cuellar became that kind of friend to Garland, who once listed her church shelter as his home address.

But their relationship quickly became much darker.

Krause wanted the three of them to have sex together, Lopez said, and Cuellar “did it to please [Krause], to make him happy. His thing was watching her have sex with someone else.”

As the weeks went by, Cuellar and Garland grew close. Krause allowed them to have sex on one condition: He had to be in the house when they were intimate there. But then they started spending time together when Krause wasn’t around.

The 49-year-old became jealous, Lopez said, especially when Krause saw how happy Garland made Cuellar, how she laughed and smiled and acted like her old self. Friends said it was obvious that she was falling in love with him. Krause eventually stopped going to his job so he could keep an eye on his girlfriend.

“He wanted to be around her constantly,” Lopez said. “She couldn’t go to the bathroom without him knocking on the bathroom door.”

::

The move to California was supposed to be a fresh start for Kandince Cuellar, a chance at a new life after four hard decades in Arizona marred by addiction and a failed marriage.

When her three daughters were in their teens, Cuellar had fallen “really hard into drugs,” said Shannon Cuellar, her oldest child. An aunt stepped in and raised the girls instead. On the advice of her high school counselor, Shannon wrote letters to her troubled mother, asking how she could live with herself after leaving her children. But she never mailed them.

Right before Cuellar left for California, she and Shannon reconciled, talking and texting every day. Shannon said she felt as if she finally had a mother again.

In a Facebook post nine months before she was killed, Cuellar credited Krause with keeping her “on track” and helping her get off probation after she pleaded guilty in 2009 to driving under the influence with a child in the car.

She told Shannon that Krause made her happy.

But over the months that followed, Lopez and other friends watched with growing unease as Garland became enmeshed in the couple’s lives, and Cuellar drifted away from Krause.

Shannon said she had lived for several months with her mother and Krause in Atwater Village. But the longer she stayed in the house on Glenmanor Place, the more frightened she became of Krause’s temper.

“He could break hinges off a door,” Shannon said. “Sometimes I said we should call the police. But my mom said, ‘No, he does this. He’ll be fine.’”

On Nov. 10, Cuellar messaged her daughter, asking if Shannon would come pick her up if she decided to return to Arizona. Of course, was Shannon’s quick response.

Later that night, Shannon called her mother, but Cuellar didn’t answer the phone. Instead, at 1:43 a.m., Cuellar texted her daughter, apologetic: “Sorry honey been dealing with Eric all day [and] all night. I’ll call you tomorrow. I love you.”

::

Cuellar was killed less than two hours later by a shotgun blast to the left side of her chest, not far from a tattoo of Tinkerbell. She was 41. She had blue eyes, dark blond hair and Eeyore inked on her left calf.

When she died, according to the autopsy report, her nails were pink and she wore a purple strapless bra. Those were her two favorite colors.

Cuellar, Garland and Krause all had methamphetamine in their blood when they died, according to the coroner’s reports. Sarah Kerrigan, a toxicology expert, said the levels detected were more than 10 times higher than would be found in a person taking amphetamines for medical reasons, such as treating attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Freeman died in February. When his house was torn down several months later, contractors found pages of his writings. Many of them talked about suicide. They have since been thrown away.

Lopez is the only person in the house that night who is still alive. But in the months that followed the shootings, she became homeless herself, sleeping on the couch of a friend in Montebello, living on $800 a month from Social Security — not enough to pay for a place of her own.

She is haunted by the same dream: Cuellar calls out her name, just as she did on Nov. 11, after the first shotgun blast rang out in the tiny bedroom on Glenmanor Place.

Marlene!

“I hear her all the time.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.