A blind heroine rules this audio comic book written for a blind audience

Chad Allen was feeling helpless. Not because he happened to be blind. He had a healthy handle on that part of his life. It was the insanely dark news cycle that was dragging him down. The sense that the world was falling apart and he could do nothing about it.

Mounting anxiety before the 2016 presidential election propelled him to do what he does best: tell stories. He created an audio comic book titled “Unseen,” featuring a blind heroine, an assassin from Afghanistan named Afsana. It is believed to be one of the first audio comic books by a blind author, made for a blind audience.

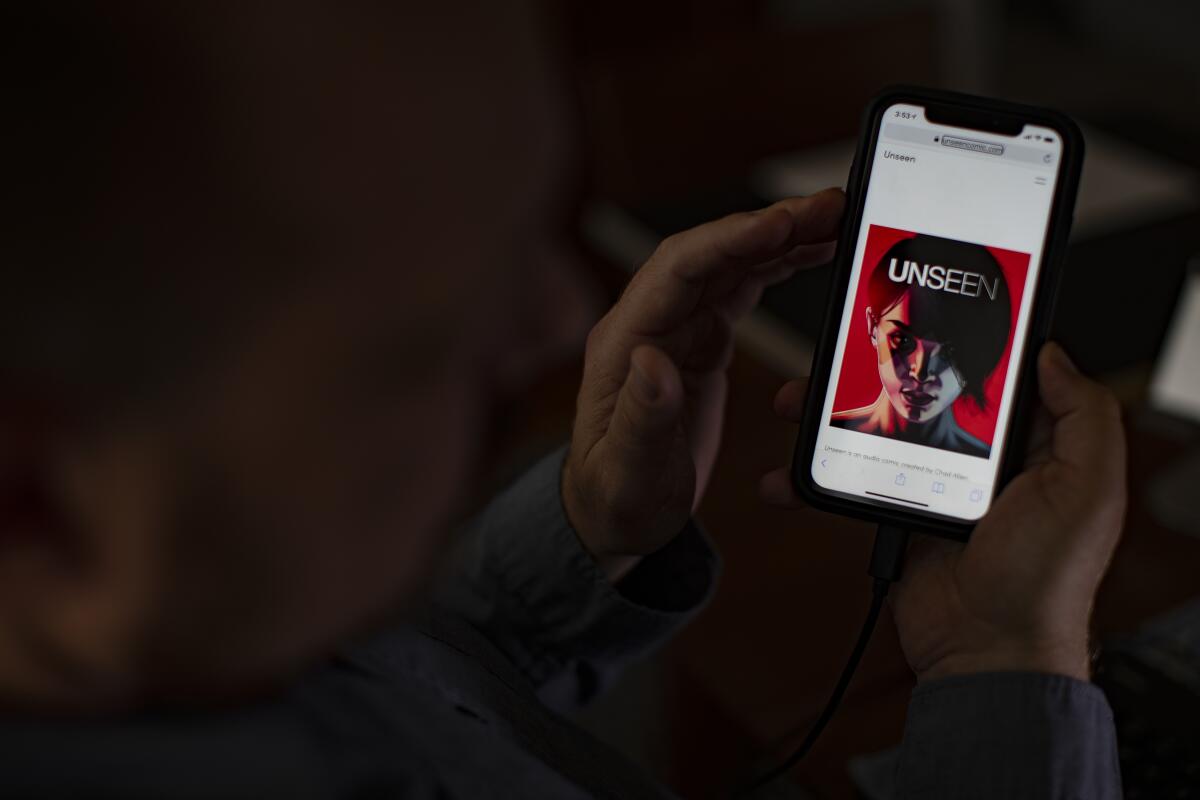

Working in a highly visual art form, Allen managed to create an auditory experience that closely mimics the sensation of reading a comic book. A whooshing sound occurs whenever a panel changes; the intentionally stilted delivery of lines, as well as narration that prompts mental images, conjure a feeling of being inside a high-stakes comic book world. Aside from a slick red-and-black graphic image of Afsana created for the cover, “Unseen” has no visual art whatsoever.

The work tied for first place in a competition for blind or visually impaired comic book writers held by the now-defunct Comics Empower store for the blind. Allen’s audio comic book also was selected for the current exhibition “Self, Made” at the Exploratorium museum of science, art and human perception in San Francisco.

“Chad’s character is written for a blind audience, but all of us can identify with her because we can identify with the experience of being underestimated,” says Melissa Alexander, the director of public programs at the Exploratorium. “His specific experience becomes more broadly applicable.”

The sense among marginalized groups — people of color, women, LGBTQ people and others — that they have been underestimated has made “Unseen” a popular part of the exhibit. It’s an exploration of human identity that uses lenses of race, gender, disability and more to help visitors explore their own biases and discover their unique identities.

Allen is thrilled to have his work included in “Self, Made” because it validates one of his main objectives in writing “Unseen.”

“You don’t see art with your eyes. You don’t see anything with your eyes. All your eyes do is filter light. You see with your brain, and that’s what I’m trying to teach to people more than anything,” Allen says, sitting in a basement classroom at Hollywood’s Magic Castle, where he has been a member magician for 20 years, wowing guests with tricks they mistakenly believe one would need sight to perform.

“I created Afsana as a barrier between my helplessness and what was really going on in the world, because she could do something. She was bad ass. She was an assassin,” he says.

Allen is quick to point out that Afsana does not have superpowers like Marvel’s Daredevil. She has a skill. Her skill is to slip in and out of places without being seen. She is not seen because people with disabilities are often not seen. They can feel invisible to society at large, Allen says.

Just the other day, he was waiting for a lane to swim laps and a number of newcomers took advantage of his blindness and hopped into the lane before him. Finally another swimmer told him her lane was free, that she had seen him waiting patiently for far too long.

“Suddenly I was visible again,” Allen says, adding he could give other examples all day long.

That’s how it is with Afsana. The catchphrase for the comic is, “Discounting her abilities is her enemies’ gravest mistake.”

The first installment of Afsana’s journey, which is available for streaming at unseencomic.com, finds her at the American border with Mexico in a not-so-distant future, when a dictatorial president is rounding up immigrants and conducting scientific experiments on disabled people with some very spooky results.

Afsana’s mission is to destroy the lab where evil Dr. Magnus conducts these experiments, a task she completes with the aid of a cane, an earpiece that delivers instructions (including where to steer a stolen bus) and a special black material that absorbs all light, shrouding her in darkness.

If this all sounds marvelously Marvel, that’s because comic books have long been an ideal medium for exploring issues of identity and otherness, says David Steinberger, a fan of Allen’s work and co-founder and CEO of the cloud-based digital comics platform ComiXology, which features content from Marvel, DC and more.

“Stan Lee created a universe of real human beings, with problems and flaws, who also had superpowers, usually hidden,” Steinberger wrote in an email. “In the Marvel universe, there’s a flawed hero for nearly anyone. Scrawny nerds — like me when I discovered comics — got to read about Peter Parker’s heroics as Spider-Man and his bullying at school; people with anger issues got the Hulk; Tony Stark is an alcoholic; and the X-Men were part of an entirely oppressed group, the mutants, that anyone persecuted for being themselves can connect to.”

Allen, 46, grew up loving comic books. He was born in Warwick, R.I., and he describes a normal, if not idyllic, New England childhood filled with bike rides, Catholic school, Saturday morning cartoons and regular excursions to the magical seaside amusement park Rocky Point.

He was not born blind. He was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa, a genetic disorder that causes vision loss, at the age of 15, around the time his parents were divorcing. His world was thrown into turmoil in a way his fragile teen psyche had trouble processing.

Stories were what saved him — telling them and building them via role-playing games with others. Making them as fantastical and far-out and complicated as possible.

He was 28, living in Denver, going to college part time and working the magic counter at a costume shop called the Wizard’s Chest, when his world went irrevocably dark. He was frightened and depressed. He began to isolate himself.

“A lot of people say life is short, but when you’re 28 years old in a basement apartment by yourself day in and day out, life is not short; life is long,” Allen says.

He needed to learn how to exist in the world as a blind person. His quest led him to the Colorado Center for the Blind in Littleton, where for the next six months he spent eight hours a day, five days a week, training to live without sight. He can’t speak of the life-changing, life-affirming value of that training, or the instructors who aided him, without choking up.

Twenty years later, Allen is sitting at his dining room table in front of a small Braille keyboard attached to an iPhone that reads emails, books and writing back to him at breakneck speed. It is hard to imagine a time when he lacked confidence in the world.

There is rabid public curiosity about blindness, says his wife, Melissa Eccles, and people are always asking the darndest questions. When their 9-year-old son, Harrison, was a baby, Allen would take him on walks in a Baby Bjorn carrier around Runyon Canyon. People either treated him like a superhero or a menace to society, Eccles says with a bemused smile.

The lack of cultural education around blindness is partly what Afsana is meant to rectify, says Pamela Allen (no relation), director of the Louisiana Center for the Blind.

“It is so important for blind kids to have superheroines and heroes who are blind, and for sighted kids to realize that disability does not mean inability; it merely means utilizing our other senses to accomplish our goals,” Pamela Allen writes in an email. “ Afsana shatters gender stereotypes as well. She affirms that it is not the lack of sight that is the issue but the low expectations that society has.”

Of all the questions lobbed his way, Allen says one of the most obvious and compelling is often asked by his son’s friends: How do you see in your head? His reply is beautiful in its simplicity.

“I say to them, ‘Do you go to bed at night? When you sleep do you dream? When you dream do you see places? Do you see people that you know? Do you see your family and friends?’ ”

When they answer in the affirmative, he asks, “Are your eyes open?“

They shake their heads.

“Well, that’s how I see you.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.