Officials fear protests are ‘super-spreader’ events for coronavirus. Marchers say worth the risk

For months, Hasani Sinclair said he has been painstakingly cautious about avoiding the threat of the coronavirus. He wears a mask. He follows health guidelines. He has repeatedly gotten tested, even without knowing of any direct exposure.

But the drumbeat of black deaths in the news propelled him to the Fairfax district on Saturday, joining the crowds that protested police brutality and bore signs with the names that rang in his brain: George Floyd. Breonna Taylor. Ahmaud Arbery.

“I cannot in good conscience let this moment pass me by,” said Sinclair, a 38-year-old high school history teacher. For black men like him, police brutality “has been a silent cause of death for years and years and years.”

L.A. Times columnist LZ Granderson speaks with protesters in downtown Los Angeles and finds goodwill and solidarity.

The collision of long-standing anger over such killings and the newer threat of the COVID-19 pandemic have become a joint crisis in Los Angeles and across the country. The coronavirus has been especially devastating to black communities, with black people making up a disproportionate share of COVID-19 deaths.

Now people outraged by deaths at the hands of police have been faced with a dilemma: How to weigh the risks of protesting during the pandemic.

For Aura Vasquez, an Afro Latina community organizer who recently ran for City Council, it was both energizing and unnerving to see the crowds in the Fairfax district.

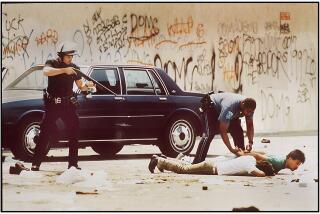

The L.A. County curfew was put in place after looting and arson amid peaceful George Floyd protests. The National Guard and police officers were out.

At one point, Vasquez said she saw a black police officer giving fist bumps to protesters. There was “a certain energy of solidarity that was beautiful,” said Vasquez, who has been spending time alone in her Mid-City home. “But I was also like, ‘Don’t touch me!’”

Mayor Eric Garcetti said over the weekend that he was worried that the demonstrations could become “super-spreader events.”

“It is not a reason to not protest — we want to find peaceful ways for people to do that,” Garcetti said. But he cautioned that L.A. needed to make sure “that we don’t have backward progress with COVID-19 in the midst of our outrage.”

The California Department of Public Health released guidelines last week for how to protest safely during the pandemic.

It warned that even six feet of distance between protesters may not be enough to prevent COVID-19 transmission when people are chanting, shouting and singing, so people should wear a mask at all times, no matter how far away they are. The agency said that if an area has a maximum capacity, attendance should be limited to 25% of capacity.

UC San Francisco epidemiologist Dr. George Rutherford described the protests as a kind of uncontrolled experiment, one that will test what happens when people are wearing masks in an outdoor setting, but yelling and not maintaining their distance.

“If you have breakdowns in social distancing and don’t have masks on, then you’re deeply in trouble,” he said.

Many protesters wore masks and some took added steps to limit transmission: Ellie McElvain, a 28-year-old comedy writer living in Echo Park, said she was worried about spreading the virus because she had recently flown to Wisconsin to grieve her grandfather.

So McElvain rolled along with the marchers from her car, holding a sign from her window and handing out water, snacks and hand sanitizer.

“It would be better if we didn’t have to fight for black lives in the middle of a global pandemic,” said McElvain, who is white. “But this is what we’re left with.”

Despite such efforts, the risks were evident. Some police officers were not wearing masks. At times, people embraced in the crowd.

Ashley Wilkerson, an actress, poet and wellness practitioner who lives in South Los Angeles, described an emotional moment after locking eyes with a police officer and urging him to hold other officers accountable, when she ended up hugging a black man in the crowd as they both cried, without their masks. Wilkerson said he told her, “You’re not alone.”

“When there’s enough love, there’s no room for fear,” said Wilkerson, who founded the Brother Breathe initiative that provides mindfulness workshops designed for black boys and men. After she left, she said, she used hand sanitizer in the car and changed her clothes and took vitamin C when she got home.

“COVID has affected us for what — two, three months?” said Wilkerson, who is black. “We’re talking centuries upon centuries of oppression — of devaluing black lives.”

Kimberly Ndombe, a 31-year-old television writer living in Echo Park, said she wrestled with whether to protest and had initially planned to stay on the sidelines handing out water. But when she arrived Saturday, Ndombe was reassured to see almost everyone wearing masks and some space between demonstrators. She joined the march.

For so long, “I’d been sitting in my house with my head spinning, thinking about this,” Ndombe said, referring to the killings of Floyd, Taylor and Arbery. “I don’t think I was the only person debating, ‘Is this safe?’ But this is bigger than us.”

Claire Garrido-Ortega, an epidemiology lecturer at Cal State Long Beach, said she felt torn about the demonstrations due to the ongoing risk of COVID-19. It is communities of color, many of the same people in the streets protesting police brutality, that already have higher rates of death from COVID-19.

“From a human perspective, as a person, we need this. Period,” she said. “From a public health perspective, I’m worried.”

Garrido-Ortega said that although many protesters appear to be wearing masks, they are also joining arms and yelling. Arrests also lead to close contact between police and demonstrators and can result in time in jail, where the virus can spread in close quarters, she said.

And people who are sprayed with tear gas may take off their masks and shout, adding to virus transmission. “Hand sanitizer? That’s the last thing they’re thinking about,” Garrido-Ortega said.

Minneapolis police backed an L.A. Times reporter and photographer against a wall and fired tear gas and rubber bullets at point blank range

Sinclair was planning to get tested again as soon as possible and was unnerved to hear Saturday afternoon that COVID-19 testing sites had been shut down across L.A.

Garcetti said that some of the centers, which are routinely closed on Sundays, would remain closed Monday because volunteer staffers did not feel safe returning. He said that the biggest testing site at Dodger Stadium would be open, along with a walk-up site in South Los Angeles.

The unrest also arrives on a backdrop of economic strain tied to the pandemic, both for demonstrators and for businesses in their path. After looting and fires broke out, the mayor lamented that businesses that were hoping to reopen were now “closed, damaged and looted.”

Along Melrose Avenue, where people were sweeping up shattered glass from the sidewalks Sunday, the pandemic remained evident.

In the window of a Mexican restaurant called Antonio’s, several signs proclaimed “Black Lives Matter,” while another stated, “Caution Maintain Social Distancing.”

Times staff writer Brittny Mejia contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.