Homeless man who died in San Clemente chronicled troubles in official court filing

About seven years into his life without housing, longtime San Clemente resident Steven Riley described his plight in an official court declaration.

“I use buildings and bushes to protect myself from the sun, rain, wind or other weather,” the then-72-year-old man wrote. “Due to my age and health, I cannot stay outside all day. But I can only afford a motel a few nights per month.”

Nearly 18 months later, Riley was found dead in front of the very senior center where he told the court he sought shelter, discovered by the director who knew him for years.

His death has devastated friends and family who’d been trying to help him, and it’s become a rallying point for local housing activists who’ve long decried the city’s lack of a homeless shelter and related services. The official court filing that chronicled Riley’s troubles well before his death also brings humanity to the ongoing web of litigation over homelessness in Orange County.

“The best I could offer my brother a thousand miles away was that he would at least die with dignity in a warm bed, with food. And then I couldn’t even get that,” Riley’s sister, Margie Lofgren, said in a phone interview from her home in Central Oregon.

Lofgren and San Clemente resident Cathy Domenichini found of the volunteer homeless outreach group iHope, developed a plan to move Riley into supportive housing for help with his medical issues, which began with childhood rheumatoid arthritis and grew to include worsening dementia in his elder years. But he broke his pelvis and was released from a hospital to a care facility in South Orange County, then checked himself out on his own and returned to the grounds of the San Clemente senior center where he’d spent so many nights.

Lofgren, who worked for decades as a registered nurse, was outraged when she called the facility and learned he’d been allowed to leave.

“Everything was in order, we had a plan for him, and he was willing to go along with the plan,” Lofgren said. “But somebody let a person with dementia walk out the door.”

“The connection between health and housing is something that has always been there, and I think the COVID pandemic is illuminating that even more,” said Becks Heyhoe, executive director of United to End Homelessness.

Domenichini located Riley outside the senior center with other unhoused men, but she warned Lofgren she didn’t think she could find a place for him to go because San Clemente and its neighboring cities don’t have shelters. Four days later, on Jan. 28, senior center director Beth Apodaca found Riley dead when she arrived for work in the morning. The coroner’s office hasn’t released a cause of death, but Lofgren said investigators believe her brother died about 4 a.m.

After attending a vigil for Riley Feb. 16, Domenichini told the San Clemente City Council his death is “the latest manifestation of a much larger and long-running tragedy” of official city disregard for unhoused people.

“Those of us fortunate to be housed in San Clemente must begin caring about those of us among us who need housing,” Domenichini said in her submitted comments.

During the Tuesday meeting, City Councilman Chris Duncan said he’s “heartbroken” by Riley’s death and believes “it’s a call to action.”

The council authorized a new homeless outreach coordinator position that night, which Duncan said is an important step “to finally address the homelessness issue in town.”

“We’re better than that, and I’m confident we will,” Duncan said.

City Councilman Gene James also suggested the city manager talk to Dana Point and San Juan Capistrano leaders about a possible regional shelter.

“I’d be the first one to jump up and down and protest placing a homeless shelter here in San Clemente; I will totally acknowledge that. But at the same time, we need some workaround on Martin v. Boise,” James said, referring to a U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals decision that bars municipalities from penalizing people for sleeping outside if no alternative shelter is available.

Citing the case, the Orange County Sheriff’s Department won’t enforce anti-camping ordinances in San Clemente and other South Orange County cities because of the lack of shelters.

“We have to find some place that OCSD can transport these people to get them off the street,” James said Tuesday.

Housing advocacy lawyers sued South Orange County cities over the lack of shelters in 2019, and the case was assigned to U.S. District Judge David O. Carter because it was deemed related to a lawsuit he was overseeing about the disbursement of a 1,200-person homeless camp along the Santa Ana River in Anaheim. But San Clemente, Aliso Viejo and San Juan Capistrano hired the international law firm Jones Day to challenge Carter’s assignment, arguing he was biased against the cities and set on forcing them to open shelters.

U.S. District Judge James Selna sided with the cities and recused Carter, and the case went to U.S. District Judge Percy Anderson in Los Angeles. Two weeks later, attorneys filed declarations from Riley and another unhoused San Clemente man, William Brown Jr., as part of their challenge to a new city ordinance that confined camping in the city to a designated lot on Avenida Pico near the city’s sewage center.

Riley said he’d have trouble walking up the hill to the lot, and that he traditionally stayed in downtown San Clemente alone and away from shared spaces “due to my age and disabilities.”

“If there were an indoor shelter with services, I would be very excited to try staying there and hope for help getting into housing I could afford based on my limited income. But, as far as I know there is no shelter in San Clemente that will take me and no housing that I can afford on my limited income,” according to Riley’s declaration.

Anderson rejected the bid to overturn the ordinance and eventually dismissed the entire lawsuit. Meanwhile, Lofgren was staying in touch with her brother via telephone, and she sensed his condition deteriorating.

He owned a landscaping business in San Clemente for years, but he struggled with alcoholism, and Lofgren said he was becoming more confused and forgetful. Still, there were consistent glimmers of the older brother she’d always known, from his cantankerous edge, sharp wit and love of San Clemente surfing history to his uncanny ability to reenact scenes from old movies.

As children, Lofgren, Riley and their brother, Greg, moved to San Clemente from Pomona with their parents in 1960 so their father, Leon Riley, could manage the now-closed Alpha Beta grocery store. Leon and Eva Riley were well known in town and involved in local politics, and Leon Riley was profiled in the New York Times and Time Magazine as President Richard Nixon’s grocer when he was at the Western White House.

Mobile cart is intended to be useful and provide dignity for homeless population.

Lofgren moved with her husband to Oregon in 1976, but she visited home regularly, and she has friends in San Clemente who helped keep an eye on her brother after he became homeless. She also tried to work with outreach organizations such as CityNet, but she said she found true compassion in Domenichini, who formed a friendship with Riley and learned his routine.

Together, Lofgren and Domenichini worked to get Riley into physical therapy after he broke his pelvis, and they were searching for a skilled nursing home where he could recover long-term when he was placed in the Capistrano Beach Care Center. Lofgren learned he’d left on his own and against the advice of medical professionals when she called to check on him Jan. 24.

Chris Oakeson, the care center’s administrator, declined comment when reached by phone last week.

Domenichini said she last saw Riley in the afternoon on Jan. 26, and she was heading to the senior center to check on him on the morning of Jan. 28 when she got a phone call telling her he had died. Domenichini said she’s sure it was hypothermia or weather related. Temperatures in San Clemente dipped into the 40s that night, according to weather reports, and Domenichini said Riley was weak, frail and underdressed.

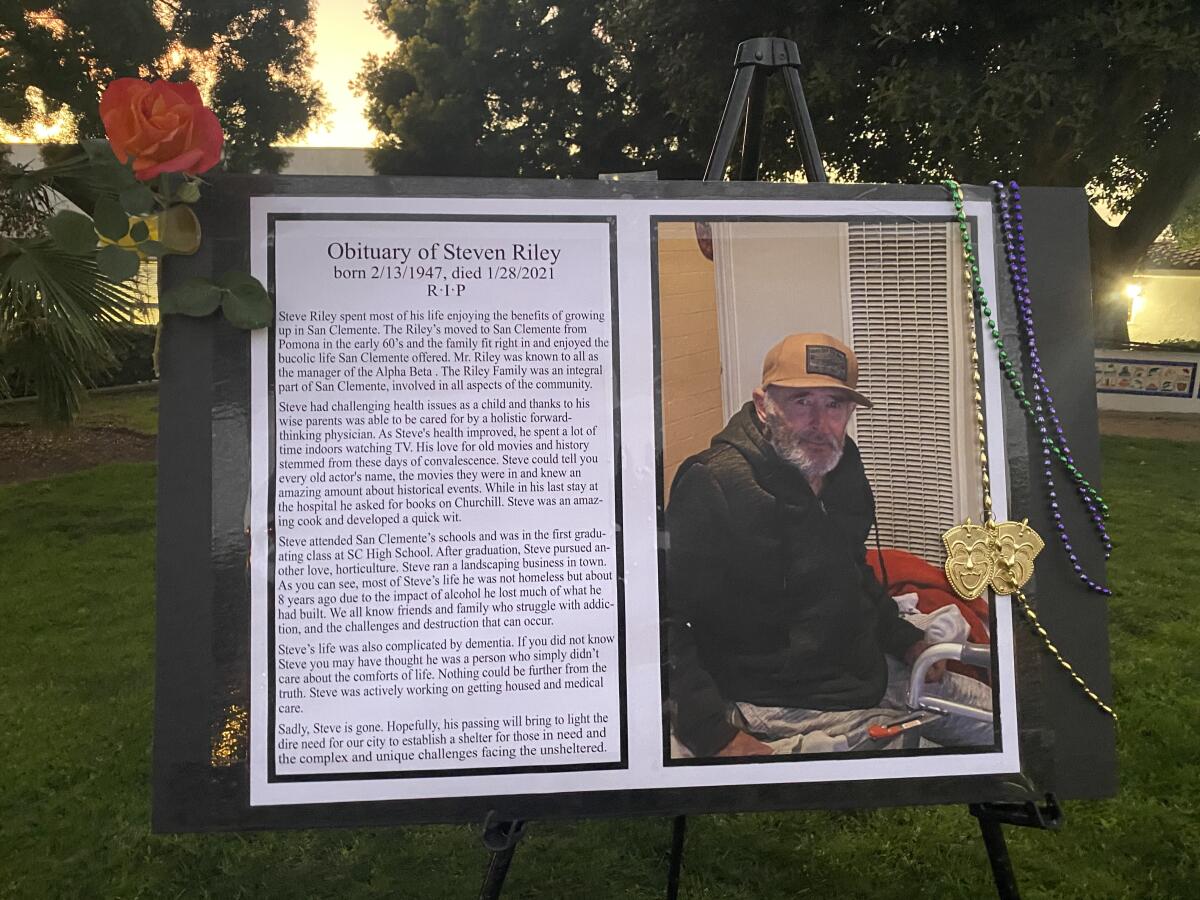

A photo of him enlarged for his memorial last week shows him bearded and smiling in a hat and sweatshirt with his walker nearby. An accompanying obituary said he’d “lost much of what he had built” to alcohol.

“We all know friends and family who struggle with addiction, and the challenges and destruction that can occur,” the obituary reads. “If you did not know Steve you may have thought he was a person who simply didn’t care about the comforts of life. Nothing could be further from the truth. Steve was actively working on getting housed and medical care.”

Domenichini said she’s hopeful Riley’s death will inspire change.

“We’re hoping some kind of good can come out of this, that people open their eyes to the disenfranchised in our community,” she said.

Meghann M. Cuniff is a contributor to Times OC.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.