In a tiny California town ravaged by fire, a muralist finds a calling — and notoriety

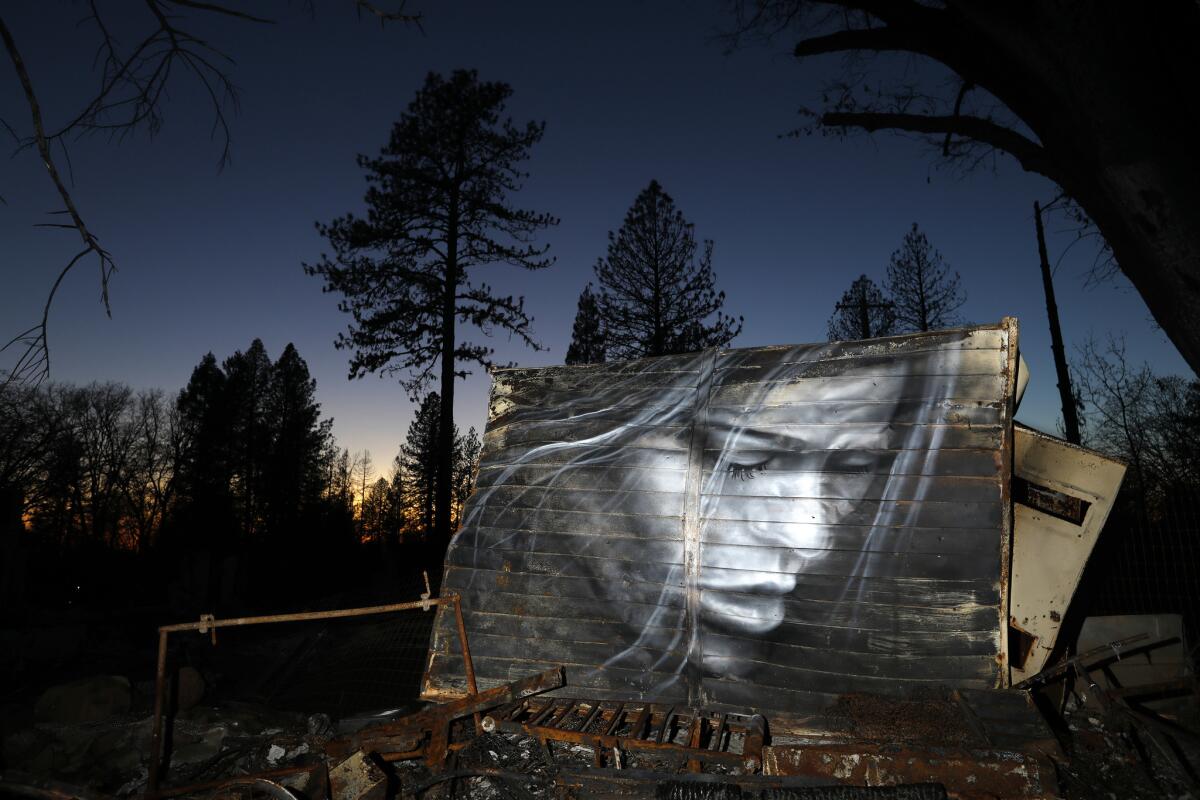

Nicole Weddig felt a strange sense of calm as she stood in the driveway, her gaze fixed on the wall.

She did not expect to ever again find peace in this town, where all that was left of her home was ash, rubble and rusted metal, the front steps that lead to nowhere, and the patchwork of singed stone.

Yet it was comforting to see her daughter’s portrait rendered delicately on the wall, her little profile squinting up into the trees, wisps of fine hair floating away from her face as if with the wind.

Eleanor had refused to set foot in Paradise in the weeks after the fire. “I don’t want to see one burned building,” the 9-year-old told her mom and dad. So Nicole had visited just twice: first to see if any belongings had survived the flames, and now, in late January, to see the mural.

Nicole had offered the wall to an old friend from Chico High School, a commercial artist named Shane Grammer, after he’d posted on Facebook the week before:

Looking to paint a few more murals in Paradise, he wrote. Anyone have a canvas?

Shane had grown up 15 miles southwest of Paradise in Chico, and could easily count two dozen friends who’d lost everything in the November fire. One of them, a Christian rapper named Shane Edwards, had shared a picture on Facebook of his property on Clark Road. The house has been completely leveled, save for the brick chimney.

Shane felt called to respond to the fire, the deadliest and most devastating in California’s history. In the chimney he saw his canvas.

That would be his first mural in Paradise. By the time Nicole messaged him, he was planning his second trip to the ravaged town.

It’s out in the middle of nowhere, she warned him. No one is going to see it.

That’s perfect, Shane replied.

When the lot is cleared and Nicole’s wall crumbles to the ground, so too will the mural. But Shane’s notoriety in the art world will have just begun to take root.

Shane has always felt compelled to make art in what he calls “downcast and brokenhearted” places: an orphanage in Ensenada, a recovery center for underage girls who have been sex-trafficked.

It’s a drive born from an unshakable belief that his talents are a God-given mandate to ease the pain of others, even if just for a moment or two.

Shane is 47 now and well-acquainted with the healing power of creativity. As a teen, he turned to art and faith to cope with tough times at home. He loved graffiti and street art. At one point, he also thought he might become a youth pastor, and in the early ’90s he fulfilled both of his passions by painting murals on the walls of rooms where church youth groups met. Later, he made stage props and sculptures for Christian youth conventions and worked for an inner-city youth mission in San Francisco.

Youth conventions led to building three-dimensional worlds for tourist attractions: a whimsical 30-foot tree for the Bellagio hotel in Las Vegas, Optimus Prime busting out of a maximum-security fortress for a traveling exhibition called “Hall of Heroes.”

He opened his own shop in the Sacramento suburbs in 1996, and the business grew quickly. Shanghai Disney and Universal Studios Hollywood were among his clients. He was doing all the sales, bringing in all the work, managing dozens of employees. But he wasn’t the one making the art, and it was soul-crushing.

“I felt like I had a thumb on me, all of this pressure, and I couldn’t be creative,” Shane said.

In 2016, he shut down his shop and moved to Southern California — where he lives with his wife and three young daughters, in Rancho Cucamonga — to freelance for theme parks. Without the overwhelming responsibilities that come with running a business, he could also pursue passion projects outside of the commercial world.

For past few years he’d been thinking a lot about art installations that incorporated manufactured ruins. He designed Photoshop renderings of abandoned buildings adorned with Star Wars characters — “like propaganda after a war,” he said. He imagined built environments where people would walk through broken concrete walls and stumble upon breathtaking murals.

Shane had a binder full of these mock-ups when the Camp fire hit Paradise. To him, this was a sign.

On New Year’s Day, after celebrating the holidays with friends and family in nearby Roseville, he set out to paint his friend’s chimney in Paradise.

In high school, Shane had played basketball against Paradise High. He had worked for a drywall company in Paradise and had helped build houses there. As he drove into town for the first time in years, it took everything in him not to pull over and weep.

“Knowing families were living here and now they were gone … ” he trailed off when he later conjured up the memory. “It was a lot to process.”

That first mural took Shane about three hours to finish. The face of a woman with a weary, vulnerable look in her eyes had been brought to life with layers of opaque white and black spray paint bought in L.A.’s Arts District.

It was as if she had been burned into brick, forged by the fire. This was by design: Shane wanted the mural to blend into the environment, as if to acknowledge that this art would have never come to be if the flames hadn’t been here first.

Shane posted a photo of the chimney on his social media accounts that night, and a few people reacted. But when Edwards, the owner of the property, shared the artwork on a Facebook page for Camp fire survivors, hundreds responded.

“Love that there is something beautiful to look at in the midst of the devastation,” one woman wrote.

“Not sure why, but this brought tears,” another said.

With the help of community members, Shane named the piece “Beauty Among the Ashes.”

It stood for seven weeks. On Feb. 25, it was knocked down by an excavator.

On a rainy morning in early April, Shane ducks into the burned-out shell of an auto shop. Glass crunches under his feet. Rain drips through holes in the roof and onto shelves of rusted mufflers. Shane’s latest canvas is a metal roll-up door, through which cars once rolled for repairs.

Two reporters from Los Angeles have come to watch him paint. These days, handling the media is like a second job. He first caught the attention of local news, and then national outlets. He painted a mural for filmmaker Ron Howard, who is making a documentary on the Camp fire with National Geographic, the day before. He would be featured on “The Today Show” later that week.

Shane thought he’d paint just the one mural back in January. But the opportunity to create more — and the motivation — snowballed after the overwhelmingly positive reception of that first piece.

He’s now traveled to Paradise seven times to paint murals. This, on the roll-up door, is his 17th.

Most of the murals have been variations of the first: beautiful women, by conventional standards. One was painted on the side of a rusted van, another on plastic wrap stretched between two trees, overlooking a canyon.

Today Shane will paint one more of these women, her eyes large and cheekbones prominent, her expression somber. Standing in a pool of water in his steel-toed boots and gray camo pants streaked with a rainbow of paints, he begins outlining her eyes and nose in black.

He is asked over and over again — why these women? Why here?

They’re an extension of a series he started over a decade ago called “The Bride,” based on the love story “Song of Solomon” from the Old Testament.

“How beautiful you are, my darling!” the king declares to his beloved in the verse. “Oh, how beautiful! Your eyes are doves.”

To him, the story is an allegory for God’s love of mankind. Just as the king loved the woman in this Bible passage unconditionally, so, too does God love the people of Paradise.

Despite this well-intentioned message, not everyone is a fan of the murals.

The most common criticism is that these women do not represent the humble and tough matriarchs of Paradise.

And some residents balk at the idea of finding beauty in the wreckage. One couple, pushing a stroller past the piece dubbed “Sleeping Woman” on Bille Road, told a reporter they hadn’t noticed this mural or any of the others.

“We try not to look at it,” the young father said of the rubble that surrounded him.

Others have characterized Shane as an opportunist. In a recent letter to the editor in the Chico Enterprise-Record, one resident called the murals a “mediocre artist’s vanity project.”

The writer accused Shane — “a punk from Hollywood” — of capitalizing on Paradise’s misery.

Shane heard about the letter, but he didn’t read it. He’s learned to let these things roll right off him. He knows that not everyone is going to like his art.

Some people believe that profiting from tragedy, whether directly or indirectly, is offensive, tacky or just plain wrong. The act has become known as “tragicrafting,” a term more commonly used in reference to commemorative wearables like T-shirts and bracelets (think “Paris Strong” and “Never Forget.”)

Shane insists that his mission here, to bring hope where there seems to be little left, is pure. He swears he’s not the type to swoop into disaster zones armed with spray cans.

“Do I become the guy that goes to tragedies and paints?” he asked himself earlier this year as he considered a mural project in Alabama, where a rash of tornadoes killed 23. “When does it end? And does that taint what I’ve done in Paradise?”

He decided against Alabama. What makes the murals sincere, he realized, is his connection to the community.

But it’s true that Shane was a relative unknown in the art world before the murals made national news, and now a well of professional opportunity has sprung up in the wake of his project’s success. In early June, Shane had an art exhibition called “Beauty from Ashes” at Chico’s Museum of Northern California Art. Hundreds attended, and $57,000 was raised.

A quarter of the show’s proceeds went to the Paradise Art Center and its summer school for trauma victims of the fire, and another quarter went to the museum. Shane pocketed the rest.

And it’s true that Shane doesn’t shy away from the press. No stranger to financial hardship, he compares his willingness to engage with the media to the frugal behaviors of those who lived through the Depression; if he sees a penny on the ground, he’s going to pick it up.

“To be in a place where so many people want my art when I usually have to fight for every gig … ,” Shane pauses.

He didn’t expect things to happen this way, he went on. But now that they have, he’d be a fool not to ride this wave while it lasts.

At noon, Shane takes a break from his auto shop mural and drives his pickup to Maria’s Kitchen on Elliott Road.

Maria Garcia, long known in Paradise for her delicious tamales, opened a catering business just a few months before the fire. Now she is trying to re-open as a restaurant. She sees a need — as of early April, there were only two other places to eat in Paradise: Sophia’s Thai Cuisine and Starbucks.

Like many others, Maria sent Shane a message of gratitude after seeing photos of the murals on Facebook. In the women, Maria sees herself. They look worried, angry, overwhelmed — emotions she has volleyed between as she processes the loss of her home and community.

But she’s noticed that others look buoyant, as if they have glimpsed the future. A Paradise reborn.

The murals that seem to evoke the most catharsis are those with ties to the community, like Nicole and her young family.

During the same trip he made the Eleanor mural, Shane painted a likeness of Helen Pace, one of 85 people who died in the fire.

Shane was an old family friend, so when he approached Helen’s daughter, Suzy Drews, about painting on the charred remains of her home, she said, sure, why not. She sent Shane a picture of her 84-year-old mother.

Memories from that nightmarish day were still fresh and reeling inside her.

The landlines were already down when Suzy tried to call her mom the morning of the fire. Frantic, she drove toward the mobile home park where Helen lived alone, but all access roads were blocked by fire trucks. I need to get to my mom, she pleaded to a firefighter.

No ma’am, he said. No one can get up there. It’s not safe.

Suzy, who has since moved to Ohio with her husband, will never know if Helen was sleeping when the flames engulfed her home or if she heard the knocks on her door from the property manager. The thought of her mom terrorized in the last moments of her life is more than she can bear.

Suzy was rendered speechless when she first saw the photos of the mural. Helen looms ghost-like over the ashen remains of the living room, where the family would gather for Christmas and Mother’s Day.

There is a look of awe on her face that was not there in the original photo. It’s as if she’s thinking: What has become of Paradise?

Produced by Justin L. Abrotsky.

laura.newberry@latimes.com | Twitter: @LauraMNewberry

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.