Op-Ed: Trump should trust his instincts, not Bolton’s, on North Korea

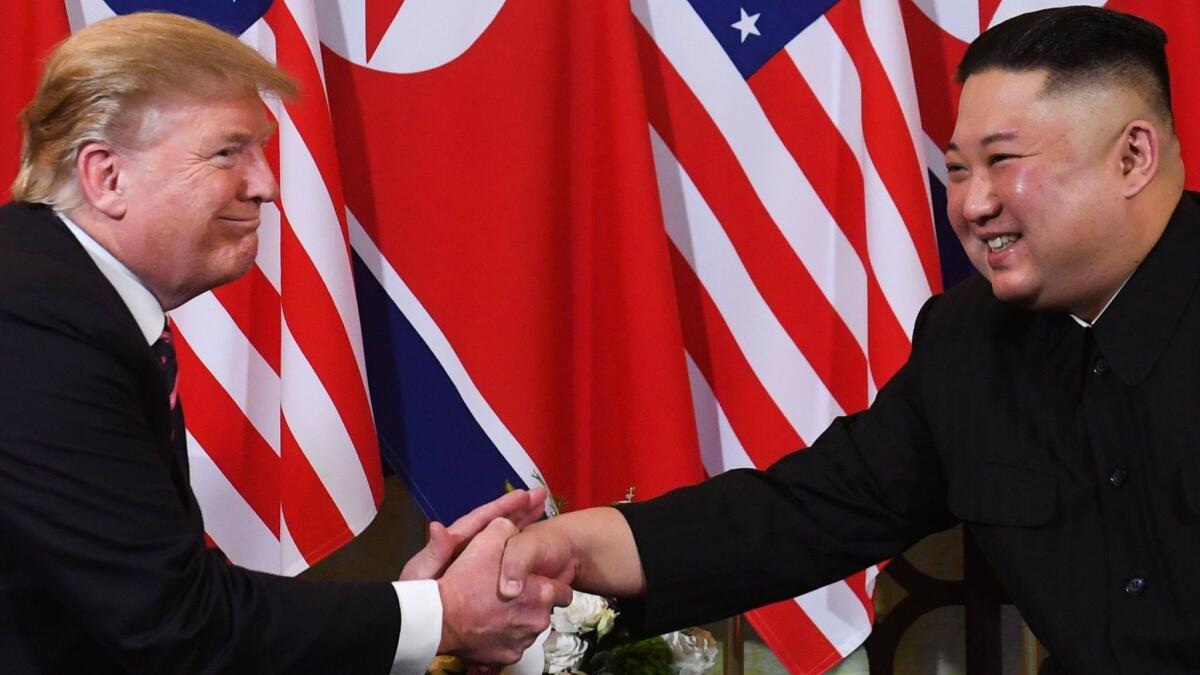

Shortly before the February U.S.-North Korea summit collapsed, President Trump handed Kim Jong Un a piece of paper. It contained, national security advisor John Bolton pointed out on the Sunday talk shows a few days later, the outline of the “big deal” on denuclearization.

Thanks to a March 29 Reuters report, we now know more precisely what the president delivered on that paper in Hanoi. It was, in part, a rehash of a “Libya model” — Bolton’s flawed recipe for total, quick surrender by a nuclear state.

Among other things, the plan insists on access by U.S. inspectors to the North’s nuclear-related facilities; a halt to all construction or activities related to chemical, biological and nuclear weapons; and transfer of all nuclear material to the United States (which for technical reasons is totally zany if it means physically transporting nuclear weapons).

The issue during the Hanoi summit was not to confront the North with our preferred final outcomes, but to get the process moving in that direction.

By and large, this is how the U.S. will want things to be at the end of negotiations, and the North Koreans already know it. The issue during the Hanoi summit, however, was not to confront the North with our preferred final outcomes, but to get the process moving in that direction. At the historic June 2018 Trump-Kim summit in Singapore, the president had pragmatically laid aside Bolton’s all-or-nothing Libya model in favor of a more feasible approach. He’d have been better off to continue that approach in Hanoi. Yet, suddenly the Libya model was back.

The Libya model — so called because it reflects Bolton’s perception that Moammar Kadafi gave up Libya’s nascent nuclear program in one fell swoop — suffers from circular logic. It assumes a country has made a final, strategic decision to abandon its nuclear program and thus is prepared to dismantle everything and ship it out. If the country will not do those things, then it must not have made such a decision and, most likely, never will. For the North Koreans, it isn’t really diplomacy; it is simply a call for their surrender. And when they saw it reappear in Hanoi, they began to worry that it meant a repeat of October 2002, when Bolton led the charge to scrap the 1994 U.S.-DPRK Agreed Framework.

We already know this tactic doesn’t work with Pyongyang, which is cautious in the extreme and, not surprisingly, may still be weighing how far to go in giving up nuclear weapons. And yet the president was advised to forgo North Korea’s offer to take a first step — dismantling Yongbyon, the center of its nuclear weapons program — and instead go for the “big deal.”

This was the same sort of bad advice that Bolton and others gave to President George W. Bush. That approach led North Korea to restart its plutonium program, which had been frozen for eight years, and build the bomb. Abandoning diplomacy again under the tattered flag of “the big deal or nothing” will have only one result: a North Korea armed with even more nuclear weapons.

Undoubtedly, the initial North Korean offer in Hanoi to trade Yongbyon for sanctions relief was vague and unacceptable to the United States. There was a need for probing, discovery, refinement and counterproposal, if not in the limited time available in Hanoi, then later. The paper Bolton has touted, however, was not a counterproposal. Nor a good chess move. It was, to paraphrase Bolton circa 2002, a hammer to smash a negotiating process he did not like. Worse, now as then, there is no practical Plan B for when it fails, just a near-religious belief in the efficacy of “pressure.”

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute from L.A. Times Opinion »

Are we prepared for what happens if the North restarts weapons and missile tests at its 2017 pace, allowing it to achieve the ability to strike the U.S. with missiles capped with nuclear warheads?

Next week, when President Moon Jae-in of South Korea arrives in Washington, there’s a chance to regain traction on negotiations with North Korea if he and Trump can harness each other’s pragmatic experience in dealing with Kim and drop the all or nothing approaches.

President Trump was on the right track in Singapore last year; he appeared to be on the right track in going to Hanoi in February. His instincts on engaging the North Koreans have proven to be sound. Following them, we began digging ourselves out from under 17 years of delusion about how to deal with North Korea until the reappearance of Bolton’s Libya model put us back in the hole.

Robert Carlin, a visiting fellow at Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation, worked for the State Department on North Korea until 2004. He is co-author of “The Two Koreas.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinionand Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.