Trees recruit army of ants to defend against invading leaf-eaters

When this tree is down in the trenches of a dry season and battling pesky leaf-eaters, it calls upon its trusty allies: ants. Ecuador laurel trees will produce an extra dose of sweet, sticky sap to attract Azteca pittieri ants that aggressively protect their arboreal home from herbivores, says a new study in PLOS Biology.

Trees and ants are often sturdy allies, said lead author Elizabeth Pringle, an ecologist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. A complex food chain can take place among their branches: Little scale insects suck sugary sap out of the tree’s innards and then poop it out as “honeydew.” The ants then harvest this processed sugary product from their herds of bugs.

“It’s basically like husbandry … it’s like us milking cows,” Pringle said.

In return, the ants protect the trees against leaf-eating critters such as caterpillars, biting at them until they roll over and fall off.

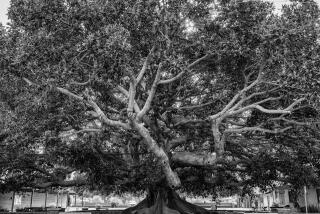

The Ecuador laurel, known as Cordia alliodora, can be found across a vast swath of Latin America, from Mexico to Argentina. But as Pringle traveled to different locations to study the trees and the ants that lived inside their branches, she started to notice something strange: The ants seemed to act very differently from location to location.

In dry, unforgiving spots in Mexico, “you touch the tree, you’re immediately covered in ants,” she said. In wetter, lusher Costa Rica, the ants were more timid.

“You almost have to cut the branches apart to even see that the ants are there,” she said.

Puzzled, the researchers ran genetic tests. Both the ants and the trees were the same species in these different spots. So why were the ants in one place far more aggressive than the ants in another?

To find out, Pringle and her coauthors studied 26 different areas across roughly 2,300 kilometers, comparing a number of factors, including how quick the ants were to respond to a disturbance, how much the trees were getting eaten by caterpillars and other bugs and how long the rainy seasons were.

They found that the drier the climate, the larger and more aggressive the ant population. A 2-meter tree in a dry spot may have 8,000 ants on it, compared to a few hundred on the same-sized tree in a damp locale, Pringle said -- and it’s probably because they’re getting egged on by the trees.

In climates where water is scarce for large parts of the year, the trees only have time to make a few leaves, and they need those leaves to make enough carbon-based food to last them through the dry season or risk dying. They can’t afford to lose any foliage to a hungry caterpillar. So rather than face an attack of leaf-nibblers, they pump out more sap to attract a standing army of ants to defend against incursions. It costs the trees some precious carbon, but this protection fee is apparently worth the price, Pringle said.

In wetter climes, where water is available and the trees can grow leaves whenever they feel like it, the trees don’t need to produce this extra treat for its insect inhabitants, and the ants are more reclusive than protective.

This adaptable, complicated ant-plant relationship “consistently amazes me,” Pringle said.

The study reveals a fascinating change in the ecological relationship between two species defined by their environment -- and it gives a glimpse at the kind of complex, unexpected changes that climate change may bring, Pringle added.