Mark O. Hatfield dies at 89; longtime Oregon senator was bedrock of moderate Republicanism

Mark O. Hatfield, whose 35 years as Oregon’s U.S. senator illuminated his conviction that Republicans could be God-fearing conservatives and also passionate advocates for ending wars and racial discrimination, has died. He was 89.

Hatfield died Sunday in Portland, Ore., his former scheduler and assistant Brenda Hart said. He had been in declining health.

FOR THE RECORD:

Mark O. Hatfield: In the Aug. 8 LATExtra section, the obituary of former U.S. Sen. Mark O. Hatfield of Oregon said that he served 35 years in the Senate. He served 30 years, from 1967 to 1997. —

Hatfield, the bedrock of Oregon’s once-robust tradition of moderate Republicanism, was a devout evangelical Christian who opposed prayer in the public schools and for years managed to negotiate common ground among the contentious environmentalists, loggers, anti-abortion activists, death penalty opponents, business owners, farmers and antiwar protesters who were his constituents in a state famous for its rollicking political diversity.

As chairman of the Senate Committee on Appropriations during two terms, Hatfield infuriated his party’s leadership by opposing the wars in Vietnam and Iraq and cast the deciding vote in 1986 against a proposed balanced budget amendment, while championing such typically “liberal” issues as handgun control and family medical leave. In the midst of the shrink-government era of Ronald Reagan, Hatfield said he saw his appropriations chairmanship as a golden opportunity for “sending dollars to social programs in desperate need.”

He angered conservationists by insisting on timber harvests from the state’s storied old-growth forests but crowned his legislative career in 1996 by preserving as wilderness the majestic 500-year-old Douglas fir and hemlock trees of Opal Creek in the Willamette National Forest as a sanctuary for nature lovers and the threatened northern spotted owl.

“He has voted according to his conscience, without regard to the politics of the matter. That by itself is unusual,” said former Oregon Gov. Victor Atiyeh, the state’s last Republican governor, an office Hatfield himself held from 1959 to 1967. “He harkens back to a period of time when people would say, “I didn’t agree with him on that, but I’m sure he had a reason for it.’ Instead of, ‘I didn’t agree with him, and I’m going to get him next time,’ which is what happens now.”

Once seriously considered as a vice presidential running mate for President Nixon, Hatfield — who said he couldn’t imagine why Nixon would have chosen him, and ultimately he didn’t — was a rogue Republican before it became fashionable.

“His courtesy and his unfailing respect for the views of others made him probably one of the most respected and well-liked members of the United States Senate,” U.S. Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) said in an interview conducted with the Hatfield Project, which is producing a documentary on the senator’s life. “The thing that impressed me the most about Mark Hatfield was his willingness to stand up for what he believed in.”

The son of a Methodist railroad blacksmith and a Baptist schoolteacher, Hatfield often said he saw government as a potential force for good, and public spending as its powerful instrument.

“As a young man I felt the call of public service and believed in the positive impact government can have on the lives of people,” he said in announcing his retirement from the Senate in 1995. “Government service has allowed me to promote peace, protect human life, enhance education, safeguard our environment, improve the healthcare of Oregonians and guard the rights of individuals. I have dedicated my public life to these principles.”

**

Mark Odom Hatfield was born July 12, 1922, in the rural logging town of Dallas, Ore., and graduated from Willamette University in Salem in 1943. He joined the Navy and served as a landing craft officer during the World War II invasions of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. He was one of the first U.S. troops to enter Hiroshima after the atomic bomb was dropped.

Those “inhuman, shock-ridden” scenes, as he later described them, inspired a lifetime of activism against war and nuclear weapons. Hatfield returned from the war to obtain his master’s degree in political science at Stanford University, then taught political science at his alma mater in Salem.

While dean of students at the private liberal arts college, which traces its historical roots to the United Methodist Church, Hatfield tells of having reached a crisis in his faith akin to the “born again” experience of many evangelicals, but which in his case was more rational than emotional.

If Jesus Christ is truly a divine savior, he reasoned during an intense moment of reflection, then the only possible response was to offer his entire life to that service.

“Define your own spiritual commitment,” Hatfield wrote later in “Against the Grain: Reflections of a Rebel Republican,” which he wrote in 2001 with Diane Solomon. “Energize your conscience. Use loving spirituality to infuse your personal, public and political acts. Take advantage of spiritual stewardship when dealing with political issues such as the environment, the needs of humans, the dangers of war.”

Former staffer Lon Fendall, who wrote a book about what he describes as Hatfield’s evangelical progressivism, “Stand Alone or Come Home” — the advice Hatfield’s father gave to his son about facing tough moral choices and relentless peer pressure — compared his boss to the 18th century British politician William Wilberforce, whose evangelical Christian convictions spurred him to lead the fight to abolish slavery. Hatfield himself, who read widely in history and political biography, was keenly aware of Wilberforce’s legacy and had written a preface to an abbreviated collection of his work.

“He said, ‘You know, I’ve been doing these things in my life in particular ways, and I’ve come to the realization that here’s a person centuries ago that did exactly the same things for many of the same reasons,’ ” Fendall said in an interview. “I think Hatfield was drawn to him because they both came to their personal faiths while already in politics and on their life pathway, and began to ask themselves, ‘What is my life pathway?’ I think Hatfield’s calling as a believer was to take on a variety of issues that many other believers weren’t ready to face.”

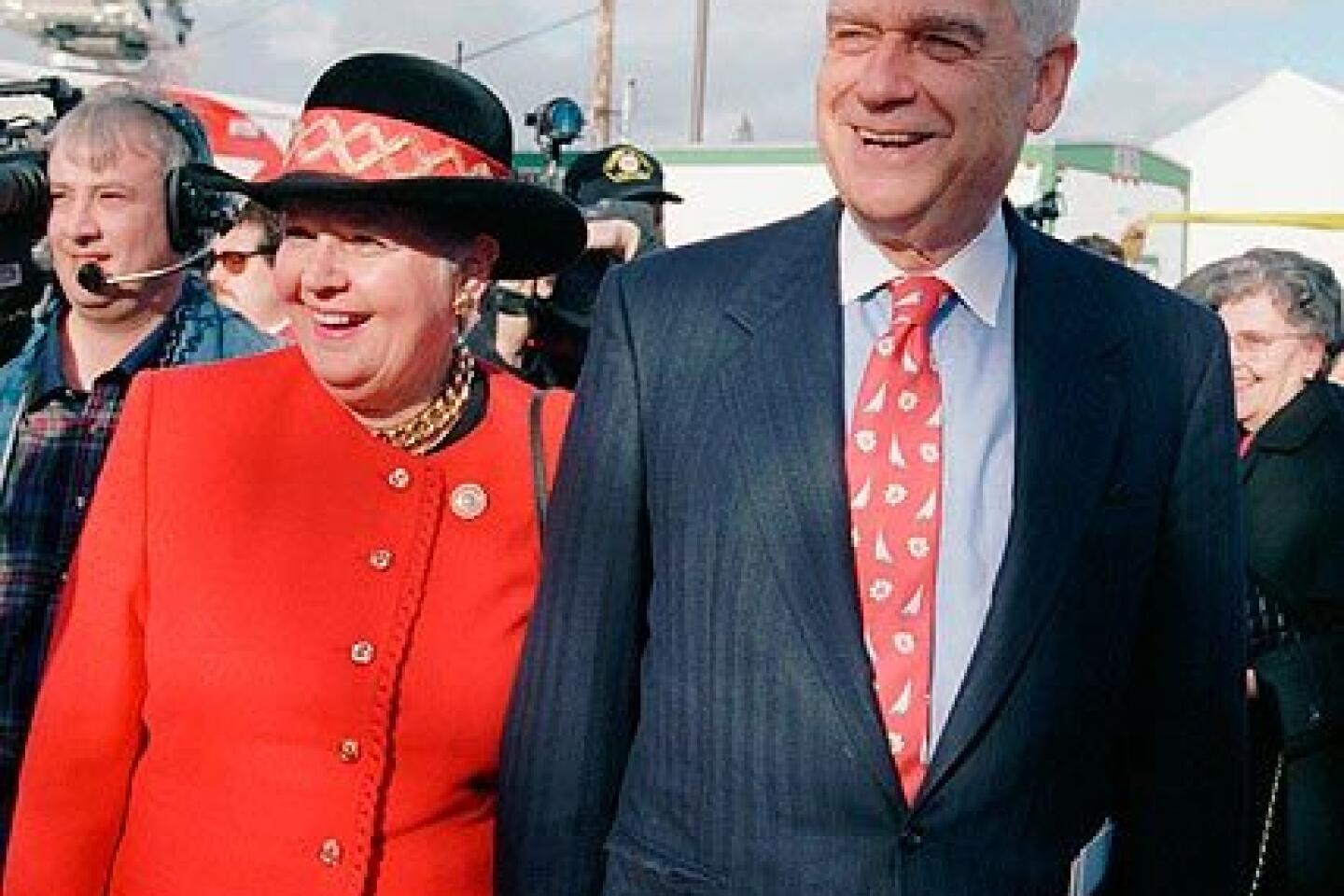

Hatfield won election to the Oregon Legislature in 1950, while still living at home with his parents, and met his wife-to-be, junior high school teacher Antoinette Kuzmanich, at a dance during his second term in 1952. With his matinee-idol good looks and engaging manner, not to mention his self-described “populist” determination to shake hands, show up at Kiwanis club meetings and speak at graduations, Hatfield was elected secretary of state in 1957 and governor in 1958.

In the U.S. Senate, beginning in 1967, Hatfield’s influence grew quickly, and he was considered one of the leading contenders to be Nixon’s vice presidential running mate in 1968.

Hatfield himself was caught off-guard. “How popular could I have been campaigning in the South, a longtime, passionate civil rights activist, dove, and former member of the NAACP?” he wondered in “Against the Grain.”

Nixon apparently came to the same conclusion and chose Spiro Agnew instead.

“He was a highly intelligent individual, fully predictable, had very high standards. You always knew how he would come down on things,” said Gerry Frank, Hatfield’s former chief of staff. The conflict with President Johnson over the Vietnam War, and later with the Republican leadership over the balanced budget amendment, were “lonely” times for Hatfield, he said. “Very difficult. But he never wavered.”

As appropriations chairman, Hatfield was able to steer vast federal sums into one of his greatest fields of interest, biomedical research. In the 1990s, he oversaw a $2.5-billion increase in National Institutes of Health research, expanding funding for Alzheimer’s, AIDS, Parkinson’s disease and sudden infant death syndrome. He helped allocate $314.5 million to Oregon Health Sciences University in Portland. The NIH hospital unit in Bethesda, Md., which opened in 2005 thanks to his stewardship, bears his name: the Mark O. Hatfield Clinical Research Center.

Reagan’s administration in the 1980s, meanwhile, had fed a growing conservative shift within the Republican Party, no less in Oregon, and Hatfield, though still widely popular, began standing on shifting sands, said Bill Lunch, political science professor at Oregon State University in Corvallis.

Hatfield had successfully weathered some ethics investigations in the 1980s, including allegations that a Greek financier had paid the senator’s wife $55,000 in consulting fees while seeking Senate support for a trans-Africa oil pipeline. His opponent in 1990, Bend businessman Harry Lonsdale, questioned his integrity during what proved to be the senator’s closest and most expensive race, from which he emerged with 54% of the vote.

Other moderate Republicans began facing tough conservative challenges, and a potential challenger already had made it clear he was going to make Hatfield answer for his balanced budget amendment vote if he ran again in 1996.

“The Republican Party had sort of marched off to the right,” Lunch said. “Hatfield behaved as a moderate, and that offended people on the right wing of the party. Ultimately, and at the time he denied it, it’s arguable that the reason Hatfield left the Senate was at least in part the fact that he [and other moderates] were being challenged by people who showed that they could have a profound influence in Republican primaries.”

Frank disputes that. “He felt he’d had enough,” he said.

Hatfield spent the latter years of his life mainly in Portland, writing, teaching and making a limited number of public appearances, though a fall a few years ago left him increasingly frail and reclusive.

“Sen. Hatfield’s contributions go beyond the policies enacted both as governor and as a U.S. senator. His contributions continue to live on through the next generation of leaders who worked for him, learned from him and for whom he mentored,” said Oregon Gov. Ted Kulongoski. “Their continued contributions to making Oregon a better place for us all is really a testament to the senator’s commitment and love for this state and its people.”

His survivors include his wife, Antoinette, and children Elizabeth, Mark Jr., Theresa and Charles.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.