Cuba under the lens at the Getty Museum

Ernesto “Che” Guevara makes several matinee-idol turns in the Getty Museum’s just-opened photography exhibition, “A Revolutionary Project: Cuba from Walker Evans to Now.”

There he is as a dashing, beret-clad guerrillero in Alberto Korda’s iconic portrait. And there, posing with his future wife, Aleida, in 1958, as the communist rebels prepared to oust the brutal Batista dictatorship. And again, vigorously pitching in with volunteer work as Fidel Castro’s minister of industry in 1961.

But the photo of the revolutionary leader that best encapsulates the show’s themes and conveys the tensions of the country in its crosshairs isn’t a picture of Che exactly. It’s Virginia Beahan’s 2004 image of a shoe store in the central Cuban city of Camagüey. A portrait of Guevara dominates the shop’s window display, but there isn’t a single pair of zapatos in sight.

Viewers are invited to contemplate whether the United States’ ferociously effective, decades-long economic embargo, the Cuban government’s misbegotten socialist policies, or some combination is to blame for turning the store, and countless others like it into a ghostly shell. Similar questions and Cuba’s many contradictions — physical beauty and stark impoverishment, political ideals and Cold War debacles, tragic failure and boundless potential — arise repeatedly in the exhibition, whose works span the early 1930s to the present.

“Part of what we wanted to do was to show people various sides of what Cuba is like now, because there is such a myth about not only its history but its current state of affairs,” says Judith Keller, the Getty’s senior curator of photographs.

“I think it’s the contradiction of the great potential you see in the people,” continues Keller, who visited Cuba last year with the exhibition’s co-curator, Brett Abbott, curator of photography at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. “There literally is music on every block and people being very productive and trying to patch up their housing. But at the same time the place is crumbling, and there is no food in the shops.”

The Getty’s unveiling of Evans’ photos from the 1930s would be an event practically all by itself.

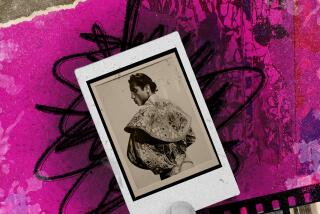

When a publisher sent Evans to Havana in 1933, his nominal mission was to produce photos to accompany a book, “The Crime of Cuba,” by radical reporter Carleton Beals, a diatribe about oppressive, unequal conditions under then-President Gerardo Machado.

Chracteristically, Evans was more attracted to the flâneur culture of Havana’s shabby-genteel streets and its architecture’s faded grandeur. His images of plantation serfs and Havana beggars, fashionable women and swarthy stevedores in rakishly angled hats, cigars and cigarettes dangling insouciantly from their lips, combine sharp social observation with formal elegance.

The Getty, which owns large holdings of the legendary photojournalist’s work, published a book of his Cuba pictures in 2001 but is displaying them en masse for the first time.

The three contemporary photographers in the show get under the country’s skin in very different ways. Beahan focuses on the historical and cultural narratives that lie hidden in plain sight in Cuba’s landscapes. Her deadpan depictions of the bay where Christopher Columbus made one of his first stops in the New World and the beach where the exiled Castro returned to start a revolution disguise their significance like undercover spies.

By contrast, her pictures of pro-government billboards dotting Cuba’s highways practically shriek out their Spanish-language slogans (“If They Invade Us, I Will Die Fighting — Fidel”).

Russian-born Alexey Titarenko turns a skeptical if sympathetic eye on what had become of Fidel Castro’s Workers’ Paradise after its Soviet sponsors withdrew their financial and military support in the early 1990s. Keller says that Titarenko deliberately photographed Havana in much the same way he’d photographed his native St. Petersburg in a previous series, “as a communist kind of Cold War city that has suffered very much from the communist policies and communist rule. And so he, with his black and white and very sort of dusty gray imagery, he is removing any spark, any color from the city [Havana], which is in fact very colorful.”

The third contemporary photographer, Alex Harris, a former student of Evans, ponders the hate-love relationship between Cuba and the United States through three very different lenses: the lives of Cuban prostitutes, the windshields of vintage American cars, and the busts and sculptures of the great Cuban poet and national hero José Martí that are ubiquitous throughout the island.

“I became very interested in the idea of Cuba, what is it people hope for, dreamed of, hoped to obtain, and I think I really found it in this one individual [Martí],” says Harris, speaking by phone from North Carolina, where he teaches at Duke University.

The ambivalent tone of the outsiders’ images is countered by the jubilant mood of photos taken by Cuban photographers during the heady days of the revolution in the early years of Castro’s rule. Some, like Perfecto Romero’s image of Camilo Cienfuegos asking Batista’s soldiers to surrender, depict actual historic watersheds. Others were staged to promote revolutionary ideology. Castro, a master in constructing his own brand of celebrity populism, grasped the propaganda value of photography and how it could be used to forge a new Cuban identity. That intent can be seen in Osvaldo Salas’ photos of young artillerymen at the Bay of Pigs, defiantly brandishing their rifles after the disastrously failed U.S.-backed coup attempt.

The Getty’s show, which runs through Oct. 2, is one of L.A.’s opening salvos in a months-long cultural salute to the island nation that’s taking place on both U.S. coasts this year. Upcoming happenings include a display of Cuban film posters at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, performances by the Ballet Nacional de Cuba in Costa Mesa and Los Angeles, a spotlight on contemporary Cuban cinema at the Los Angeles Film Festival, and an Aug. 24 Hollywood Bowl concert headlined by the Orquesta Buena Vista Social Club.

A recent easing of travel restrictions between the countries may permit more such cultural exchanges. That could broaden perceptions of Cuba on this side of the Florida Straits, beyond postcard images of white-sand beaches or bleak impressions of tattered buildings and empty store shelves.

“It’s a very picturesque place, and one of the challenges is capturing it in a way that goes beyond the picturesque,” Abbott says. “There’s so much politics wrapped up into all of this. But I think especially the contemporary photographers are trying not to be political, even though there are political undercurrents.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.