A Tunisian state police officer shares harrowing inside view

He glances over his shoulder. Not here, he says.

In the shopping center across the street, there’s a cafe downstairs. He picks out a table in the far corner, behind a pillar, to shield his face from security cameras, as jumpy as a fugitive.

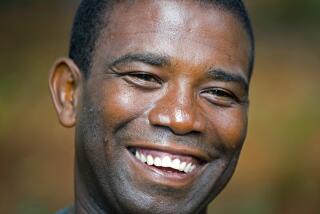

Except that Najib, 32, is a member of Tunisia’s state security forces.

During the protests that toppled President Zine el Abidine ben Ali, he was ordered to put on a helmet, hold up a shield and baton, and stand against his own people.

He went through the motions, but in the end he didn’t have the heart to raise his baton against them.

Even with Ben Ali gone, he is reluctant to talk about life as a policeman in a police state. His commanders at the Interior Ministry don’t know that he failed in his duty, and they have ordered officers not to talk to reporters.

Still, Najib decides to risk it, on the condition that only his first name will be published. With gentle encouragement from his wife, a 30-year-old schoolteacher named Dhekra, he tells his story, the words pouring out.

“The dictator is gone,” he says, speaking quickly and in hushed tones. “But the dictatorship is still here.”

*

In Tunisia, as in other Arab countries, the Interior Ministry has long been the Ministry of Fear, an instrument used by unpopular rulers to keep a restless population in its place.

It is where friends or relatives would disappear for hours or days and emerge shaken, a little different, unable or unwilling to talk about what happened. It was home base of the plainclothes officers who stormed political meetings and the riot police who stood against protesters.

During recent anti-government riots in Tunisia and Egypt, protesters made a point of sacking police stations, Interior Ministry outposts, throughout both countries.

Demonstrators continue to gather in front of the Tunisian Interior Ministry headquarters, now surrounded by barbed wire and protected by the army. Some are teachers, lawyers, street cleaners and even police officers shouting for more rights and better wages. Others come just to stare at the building.

The very act of standing in front of the gray Soviet-style compound of glass, steel and concrete is cathartic.

“It’s the symbol of the repression,” says Yacine Labib, a lawyer. “If you go there and scream, it’s a kind of therapy.”

Najib says he joined the ministry’s forces seeking financial security. His father, a bus driver, was always short of money, and Najib wanted to do better.

He went through a year of police training that he describes as abusive and humiliating. After 12 years on the job, his salary is $67 a week, less deductions for his uniform and other expenses. He described a stifling, paranoid atmosphere within the security apparatus.

He was trained to use a gun, shown how to huddle with fellow police officers and hold a line against an angry crowd. But much of the training, he said, was meant to dehumanize and humiliate him and his fellow recruits. Commanders screamed obscenities at them constantly, he said.

Before he could marry Dhekra, his childhood sweetheart, he had to ask superiors for approval because she observes Islamic dress codes. It took six months for ministry officials to vet her background and satisfy themselves that she wasn’t an extremist, he said.

The couple said that another security policeman applied for permission to marry a Frenchwoman and was denied.

If Najib wanted to visit a city outside the capital, he had to get approval. He was barred from voting or obtaining a passport to travel abroad.

“I was always under surveillance,” he said.

During his years of service he worked rotations in different units. Each, he said, had its own indignities.

He served tours in the rapid intervention force, on standby to put down any unrest. Until the recent upheaval, political demonstrations were rare, so mostly he and his fellow officers beat up and arrested drunken merrymakers, releasing them after a night in the lockup and shaking them down for bribes, he said.

Traffic duty was the worst. He stood in the middle of an intersection for 12 hours without any authorized break. He was assigned a quota of tickets, and if he didn’t fine enough people, his pay could be docked.

He stood guard at soccer matches. Occasionally melees erupted, and Najib and his fellow officers cracked heads with impunity, he said. But mostly he stared down rowdy spectators, enduring the contempt of fans as well as harsh treatment from commanders.

“I need a pack of 30,” one commander said to an underling, referring to officers standing guard as unruly fans left a match.

“They’re not a pack,” the second commander said, according to Najib. “They’re human beings.”

For that insubordination, the underling was jailed for a week, Najib said. The message was clear:

“You follow orders. You keep your mouth shut.”

*

During the massive street demonstrations, Najib worked 18-hour shifts trying to keep order in the capital and the suburbs. He was bused from district to district and slept in police barracks.

On Jan. 11, Najib and about 100 other officers were assigned to guard a police station in a poor suburb of Tunis. The dam of fear that held the people back had broken, and thousands had gathered around the station.

The officers were ordered to beat the demonstrators, who were armed with Molotov cocktails and clubs.

“The regime wanted a confrontation between the police and demonstrators,” he says. “But I couldn’t do it. I ran. I ran and ran. I left my post. The people are my family. They are my brothers.”

Plenty of other officers did fight the demonstrators. One clubbed a 26-year-old interpreter as he left the office of a political party. Days later, the officer was spotted in uniform along Avenue Habib Bourguiba, the capital’s main thoroughfare.

“Why did you hit him?” a reporter asked the policeman.

“I hit him?” the officer replied.

He took a deep breath.

“If you wore this uniform and you worked the hours I worked for the number of days I worked and got paid the amount of money I got paid,” he said, “you would hit him and do even worse.”

*

With Ben Ali gone, protesters turned their rage on the Tunisian security police, likening them to “dogs” guarding their rulers’ castle.

The home of Najib’s father was vandalized. Dhekra was outraged. “The police were victims of the regime too,” she said.

Finally, the police themselves took to the streets, demonstrating for better wages and appealing for understanding from the public. They spray-painted graffiti along the city’s main boulevard: “The police say no to the dictator!”

“We’re not dogs!” said Iyad Fathi, a 42-year-old officer who has been on the force for 23 years. He said he has to feed five children and a wife on a salary of $76 a week. “I am unable to pay rent with what I have left at the end of the month.”

After a few hours sleep, Najib joined the protest. Dhekra went too.

“I took this job because I needed the pay,” Najib said. “I want to be a police officer just like the police in America and work eight hours a day. I don’t want anything else. Just my right.”

Daragahi recently was on assignment in Tunisia.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.