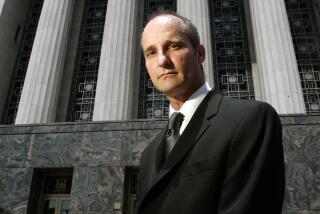

Great Read: He’s no longer a prisoner of the war on drugs

The excitement had been building all day. On election day 2008, every TV in the prison was tuned to the news.

By the time the first presidential returns began to crawl across the screens at the medium-security federal prison in Yazoo City, Miss., the number of inmates gathered to watch had topped 100. Billy Ray Wheelock was one of them.

Wheelock was doing a life stretch out of Texas without the possibility of parole for possession and conspiracy to sell about 3 ounces of crack cocaine.

For years, he and his fellow inmates had closely followed presidential politics, rooting like sports fans for the candidate promising drug sentencing reform. Wheelock had watched George W. Bush and Bill Clinton win elections. Now it was Barack Obama’s turn.

Maybe this guy, Wheelock thought.

Wheelock had been sent to prison in 1993 at age 29 during an era of no-mercy drug sentencing. At the height of the country’s war on drugs, crack cocaine offenders were locked away by the tens of thousands, often with no key in sight.

Most were men, most were poor, most were black.

Wheelock was all three.

His story embodies what many, including judges and former prosecutors, now see as a judicial system gone wrong. He is the first to admit he was guilty and deserved to do time. He had been arrested three times on crack charges.

But he says he was never violent and never owned a gun. He says he only sold a bit of rock sometimes to make ends meet. “For that I got life? Life?”

Years passed and Wheelock waited, sure someday someone would see that his punishment did not fit his crime.

When President Obama was elected, Wheelock had been in prison for 15 years. He thought maybe a black man in the White House would understand in ways no one else had. He doesn’t know why he didn’t write immediately. Finally, in 2011, he picked up a pen:

“Greetings Mr. President. My name is Billy Wheelock,” his letter began. He wrote page after page in longhand, telling of his life, his ambitions, of his belief he had been wronged. “I have already done the longest sentence for a non-violent act that has transformed me from a young man to an older man.”

For two years there was silence. Then on Dec. 19, 2013, Obama announced that eight nonviolent drug offenders would be granted early prison release, declaring they “had been sentenced under an unfair system.”

Billy Ray Wheelock was going to be free.

::

In 1986, Congress created a mandatory drug sentencing law and took aim squarely at crack cocaine. Under the law, a person convicted of possessing 5 grams of crack would get the same five-year sentence as someone selling 500 grams of powder cocaine.

Since 1980, there have been an estimated 45 million drug arrests in this country. The number of people in U.S. prisons for all crimes has quadrupled from about 500,000 in 1980 to 2.2 million now, “and that growth was disproportionately driven by the drug war,” said Marc Mauer, executive director of the Sentencing Project, a Washington research and advocacy group.

In the beginning, many in the judicial system were true believers, certain that if a person knew harsh sentencing awaited him he might think twice about selling drugs. But as the millennium turned, judges began to complain that their discretion had been stripped away by mandatory sentencing. Lawmakers also questioned not only the fiscal responsibility of keeping so many locked up for so long but also the humanity of such a stark racial divide, since crack cocaine disproportionately imprisoned minorities.

Calls for reform were bipartisan. In 2010, Congress showed rare unity and passed the Fair Sentencing Act to reduce the disparity between crack and powder cocaine sentences.

“You know you’re on to something when you have the Koch brothers, George Soros and Grover Norquist all on the same side,” said Nathan Jones, a postdoctoral fellow in drug policy at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.

::

In 1993, the U.S. attorney’s office in Waco, Texas, offered a plea deal of up to 20 years, but Wheelock wanted to take his chances with a jury. The trial lasted four days and the jury deliberated for only a few hours before finding him guilty on all charges. Days later the judge pronounced the sentence.

“Mama, they gave me life,” he recalled wailing into the phone from the holding cell. His 6-foot, 230-pound body began to shudder, his heart pounding against the panic.

“Now, boy, you stop that,” Rosa Nell Wheelock, now 72, remembers telling her first-born. “You be strong and trust in the Lord.”

Wheelock said his goal from Day One was to find a way to get out. He learned to cook, figuring no inmate would mess with him if he made good food. He converted from Baptist to Islam and became a model prisoner. “Once a person gets that kind of time they fall prey to the gangs and the drugs. You have nothing to lose anymore. I knew I had to keep myself away from all that. I stood alone.”

In summer 2012, believing he would someday be released, Wheelock joined an online Muslim marriage site and posted that he wanted to marry “a woman of substance.” He did not mention he was in prison.

Wheelock never had trouble attracting women. He fathered five children before going to prison. “All my life I’ve done it the wrong way. I wanted to do it right,” he thought.

At the same time, in Denver, Berna Lang, divorced and then 62, told her grown daughters that she did not want to grow old alone. She had converted to Islam as a young woman but was skeptical of the Muslim marriage site. Still, there was one profile that attracted her. The poster’s name was Billy Wheelock.

He’s locked up, a daughter guessed. Lang didn’t care. She wrote: “Keep your head up. I commend you for being a strong man.” She included her phone number.

Their first phone call lasted 15 minutes, the limit for prisoners. Within months he asked her to marry him. He bought a ring online and mailed it to her. He requested a transfer from Mississippi to a Colorado prison.

Lang heard from plenty of doubters. But she believed she had found someone with a good heart. Even if he never got out she made him a promise: “If this is the life God has chosen for me, I am willing to love you forever.”

On July 20, 2013, they met face to face for the first time. Wheelock dropped to one knee and proposed for a second time.

::

“Hey, Billy, they calling for you.” Word was out that Wheelock had been summoned to the warden’s office. It was Dec. 19, 2013, just before lunch at the Federal Correctional Institution in Florence, Colo.

Wheelock had bounced between four federal penitentiaries since 1993, but was rarely in trouble. He had no idea what was up. Mostly he was annoyed he might miss lunch. “It was chicken Wednesday, and I love my chicken.”

Warden Theresa Cozza-Rhodes was shuffling papers, barely able to keep a straight face. Finally she blurted the news: “Billy, it happened.”

Wheelock still cannot tell the story of his release without tears.

On April 17, the last remnant of captivity was snipped off when an ankle bracelet was removed at a halfway house in Denver. At age 51, after 21 years in prison, he was free.

Two days later, Wheelock and Lang married. Their first dance at their wedding was to Etta James’ “At Last.” A “Just Married” plaque still hangs from the fireplace in their apartment.

Wheelock is getting used to having a say in his life, to having choices. Sometimes he boards a bus and rides to the end of the line, reveling in the fact that no one is telling him where he has to get off or when.

Lang is getting used to being married again. She gets butterflies in her stomach and thinks at age 64 she might be in love for the first time.

Wheelock does not have a job; he is spending his days working on a book. He hopes to become a motivational speaker. His parole officer is helping to arrange a visit to a prison so he can talk to the inmates. He traveled to Washington to meet with leaders of the Families Against Mandatory Minimums organization.

At the University of Denver, associate professor Arthur Gilbert, a U.S. drug policy scholar, is using Wheelock’s case as course material. Last spring, Wheelock made his first public appearance in one of Gilbert’s classes. A circle of spellbound students, who moments before had been checking emails and searching the Internet, fell silent and let their laptops go dark as Wheelock began to speak.

He feels anger at all the time he lost in his life but works to tamp down those feelings. He prefers to look ahead. “I know I am still healing. I’ve got to catch up. I was 29 years old for 21 years,” he says.

Sometimes he wakes in the dark and isn’t sure where he is. In that moment it all comes rushing back; he is still inside, hearing the screams of others, feeling the old despair. Though he believes the saying “You do the crime, you do the time,” he wonders what the war on drugs really accomplished.

“I want to fight for those still in who are just like me. There are a lot of them,” Wheelock said. “I can’t really be free until I help them be free.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.