Getting up to date on a 19th century L.A. activist

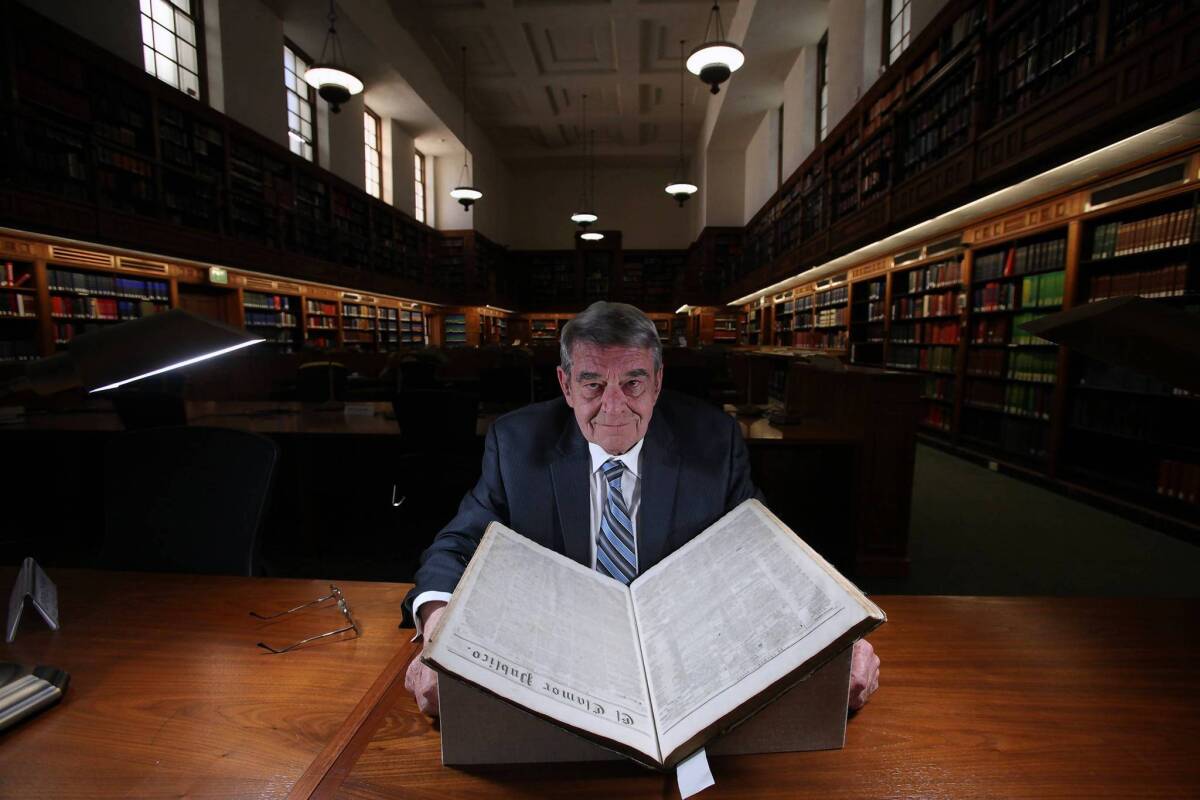

Under the watchful eye of a librarian at the Huntington, Paul Bryan Gray gently turns the delicate pages of an 1855 edition of El Clamor Público, Los Angeles’ first newspaper published entirely in Spanish.

These bound volumes are like old friends for Gray, who spent two years reading every line during more than a decade of work on his new book “A Clamor for Equality,” a biography of El Clamor‘s remarkable 18-year-old editor, Francisco P. Ramirez.

“I was fascinated by this guy Ramirez,” says Gray, 74. “He was a civil rights activist when people didn’t talk about it. He was a community organizer before there was such a thing.... He was opposed to slavery when most people weren’t. He favored co-education, that girls and boys should both be educated, a very advanced attitude. And I just liked him. He was earnest, sympathetic, intelligent. He seemed like a really appealing individual.”

And he was outspoken. Like most newspapers of that era, El Clamor was known for its spirited writing and Ramirez editorialized freely.

For example, in 1856 he wrote several impassioned pieces about the sensational murder of Evening Bulletin editor James King of William by corrupt San Francisco City Supervisor James P. Casey. (Casey was given a fair trial and hanged, Gray says).

Gray translates: “Mr. King has died for having told the truth! A noble sacrifice! While he occupied the editorial chair, he denounced evil-doers and did everything possible to protect the public.”

Ramirez was so outspoken that by the time El Clamor ceased publication after 41/2 years, he had alienated nearly everyone in Los Angeles. He angered whites, many of whom were Southern sympathizers, with his attacks on slavery and calls for racial equality for Mexicans, blacks, Chinese and Indians. He antagonized what Gray calls the wealthy “ranchero elite” by opposing their conservative politics.

“And the Mexicans didn’t like him,” Gray says. “He kept trying to get them to change from this hidebound traditional society, very conservative, owned by the ranchero elite, into a more vibrant, democratic world.”

And so Ramirez faded into obscurity until emerging in Leonard Pitt’s landmark text “The Decline of the Californios,” which Gray read while in law school in 1966. In concluding his chapter on El Clamor, Pitt dispensed with Ramirez after 1872 by saying “thereafter, one hears nothing of him in Los Angeles.”

“And I thought, wait a minute,” Gray says. “He didn’t just disappear. What happened to him?”

It was no easy task to reconstruct the life of a man who died in anonymity. Gray began reading Los Angeles newspapers of the period, finding traces of Ramirez. “Then I lost track of him in 1880. He just seemed to disappear off the planet,” he says.

So Gray embarked on a journey to libraries from UC Berkeley to archives in Hermosillo, Mexico. No detail was too trivial to pursue. Gray even located the site of Ramirez’s boyhood home and its adjoining vineyard just east of downtown near the 101 Freeway, along Ramirez Street, which was named for the family. “If you are standing in the parking lot of Denny’s restaurant and look at the freeway, dead south, the original Ramirez adobe was in the No. 4 lane of the westbound freeway,” Gray says.

Gray eventually discovered that the crusading, idealistic Ramirez, by this time an attorney in Los Angeles, had become involved in helping a man cash a fraudulent certificate of deposit. Before Ramirez could come to trial, he fled to Mexico, where he died in Ensenada in 1908, Gray says.

And why is an obscure editor of a nearly forgotten newspaper relevant today? Gray explains: “When Ramirez started his work, Los Angeles County was overwhelmingly Mexican. Now... Los Angeles County is more than 50% — I would like to say Mexican but probably it’s Latino.”

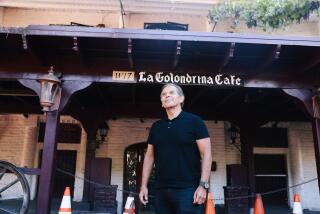

The average Angeleno may find the Raymond Chandler era appealing, with its noirish cast of characters and glitter of old Hollywood. But Gray prefers the days of the adobes, when life centered on the Plaza, with the Mexican Sonoratown on one side and the Anglos on the other.

“I’ve always thought that it was very interesting to see when cultures come in contact and what happens,” he says. “I was really interested in reading about the first Americans to arrive in California back when it was Mexican territory and what they did.”

What Gray discovered was that the first Americans adopted the local customs, used the Spanish form of their names, converted to Catholicism, learned Spanish and married Mexicans.

“And the question arose in my mind: If there had never been a Gold Rush, how far would this thing have gone? Would we form a new culture, a new society? Would we have some sort of garden spot in Southern California where people spoke Spanish and English interchangeably? Where both cultures had fused? And it damn near happened.”

That is, until the arrival of the railroads, which brought an influx of Anglos by the mid-1880s.

“The railroad ended the world as we knew it,” he says, citing the example of Judge Ignacio Sepulveda, who resigned in 1883 and was essentially the last Mexican elected to the bench in Los Angeles for 74 years.

Now that his book on Ramirez is finished, Gray has taken on a new, ambitious project: A two-volume history of the Mexican people in California. He was approached about updating W.W. Robinson’s landmark book “Lawyers of Los Angeles,” but he declined. “Can you imagine plodding through all the old law records?” he asks.

“My first love is Mexican California. What it is and what it should have been,” he says. “I’d rather write this history of Mexican people in California. I might just have enough time left to do it.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.