Losses mount as L.A. and Long Beach port strike persists

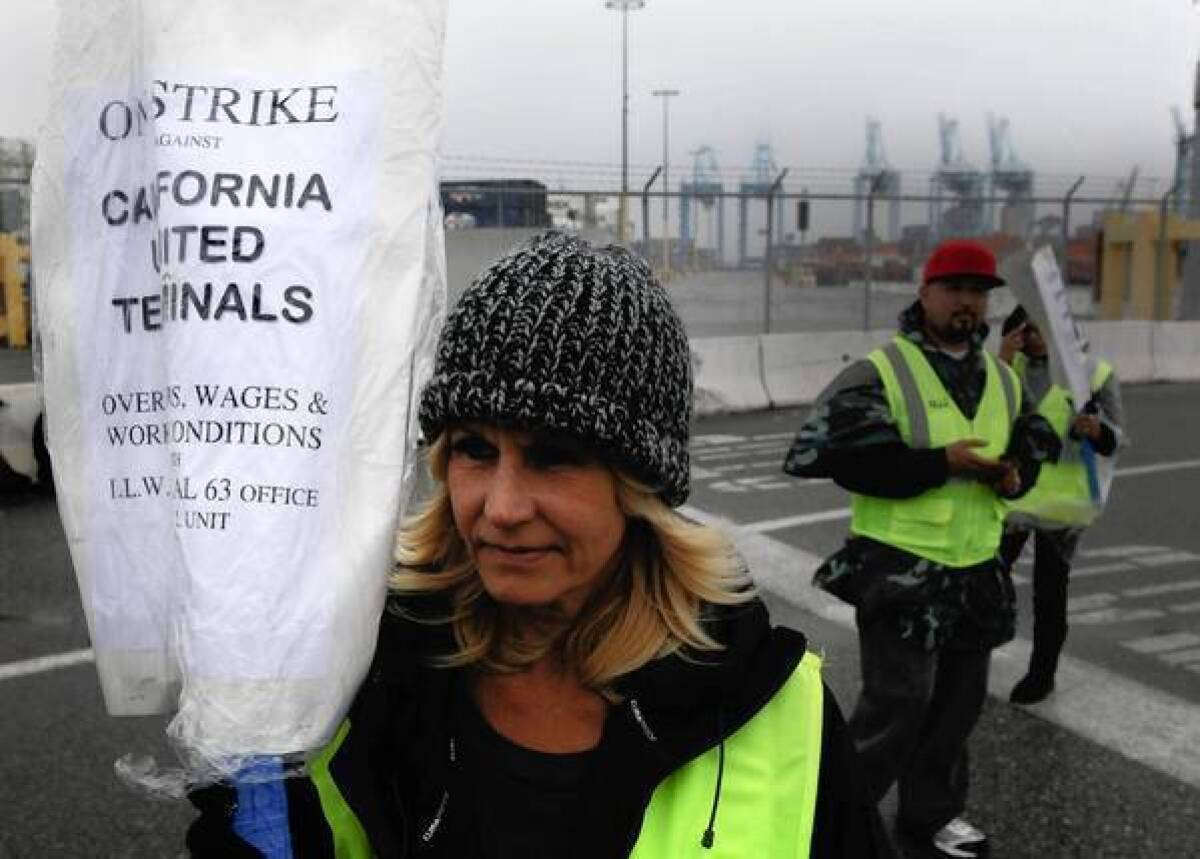

Losses mounted Friday for the strike-hobbled local ports, where picketing clerical workers have closed nearly all cargo terminals at the nation’s busiest shipping complex.

The strike by the 800-member clerks union, which began Tuesday, is creating losses estimated at $1 billion a day, including forfeited worker pay, missing revenue for truckers and other businesses and the value of cargo that has been diverted to other ports.

Seven more ships unwilling to endure the uncertainty of delays at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach streamed Friday toward competing harbors. That’s on top of the loss Thursday of two ships, which took their cargo to other destinations, according to the Marine Exchange of Southern California, which tracks vessels for the ports.

The nine ships represented more than a third of the container vessels that arrived on those days, but several that stayed were anchored offshore unable to unload, said Marine Exchange Executive Director Dick McKenna. The diverted ships headed to Oakland, Mexico and the Panama Canal, he said.

The clerical workers’ picket lines, which have shut 10 of 14 terminals, are being honored by the 10,000-member International Longshore and Warehouse Union Local 63, whose workers man the docks.

Clerical workers had been on the job without a contract for 2 1/2 years before negotiations broke down Monday. Talks between striking workers and a 14-employer management group resumed Thursday night, and union members huddled in a caucus Friday, preparing to continue negotiations.

Port officials, who act as landlords to the shipping lines, sounded a note of alarm Friday as ships slipped away.

“A quick resolution is critical to maintaining our status as the country’s premier gateway for trans-Pacific trade and we urge the parties to come to agreement soon,” said Port of Long Beach Executive Director J. Christopher Lytle.

Economist John Husing said each diverted ship represents a blow to the regional economy. A typical cargo ship carries five warehouses’ worth of goods.

“Any time an action reduces the reliability of the ports to be able to move goods into and out of the U.S., they reduce the competitiveness of the region and help make the argument that Southern California’s competitors make to move trade and jobs to them,” said Husing, founder of the Redlands consulting firm Economics & Politics Inc.

The ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach are directly responsible for about 595,000 jobs in Southern California and indirectly support an additional 648,500 jobs, Husing said.

Los Angeles and Long Beach rank first and second in the nation in the amount of container cargo they handle. For the first nine months of the year, the two ports handled almost 56% of the dollar value of cargo imported to the U.S. from Asia, Australia and New Zealand, said Jock O’Connell, an international trade economist and an adviser to Beacon Economics. About $1 billion a day in freight moves through the ports at this time of year, he said.

The diversion of some cargo to the Panama Canal Zone area was of particular significance to Wally Baker, president of the Jobs 1st Alliance, a group established to build a bridge between local labor and business to address the threat to the Southern California ports that the canal presents.

In 2014, a new set of locks that can accommodate much larger ships is expected to open in the Canal Zone, beefing up its ability to compete with Los Angeles and Long Beach for cargo destined for the eastern half of the U.S.

“The first sign of trouble, and cargo starts diverting,” Baker said. “Both sides need to sit down and get this thing fixed before it gets out of control, for the good of all of the people whose jobs depend on these two ports.”

The union, officially known as International Longshore and Warehouse Union Local 63 Office Clerical Unit, said the dispute boils down to fear that its membership would shrink through attrition as employers send work to lower-paid employees elsewhere.

The employers — some of the nation’s biggest shipping lines — say they reserve the right to fill only those jobs that they decide need to be filled.

The union has some of the highest-paid clerical workers in the U.S. The employers say they have offered a wage package worth an average of $195,000 annually, up from $165,000.