Cambodian Music Festival salutes tradition, new artists paving the way

When Bay Area singer-songwriter Laura Mam asked her mother to translate lyrics into Khmer, it was as if she had laid a bridge between worlds. Mam knew her parents had fled the Khmer Rouge — a communist-inspired movement that killed an estimated 2 million of its own citizens between 1975 and ’79. And she knew there was a time before the destruction when women sang rock ‘n’ roll and men danced the twist. But she didn’t know how to fill the distance that had grown between her and her mother.

That is until they started writing songs together.

The silence yielded, and the two began to talk. Her mother, it turned out, had a knack for poetry that matched her daughter’s lyrical gifts. Through songwriting, they shared stories of the past and dreams of the future — for themselves and for all Cambodians. The songs they wrote have now caught the ears and hearts of thousands of Khmer-speakers across the globe.

Mam hopes that next week’s inaugural Cambodian Music Festival, where she is set to perform, will encourage Cambodians to begin personal and creative dialogues of their own.

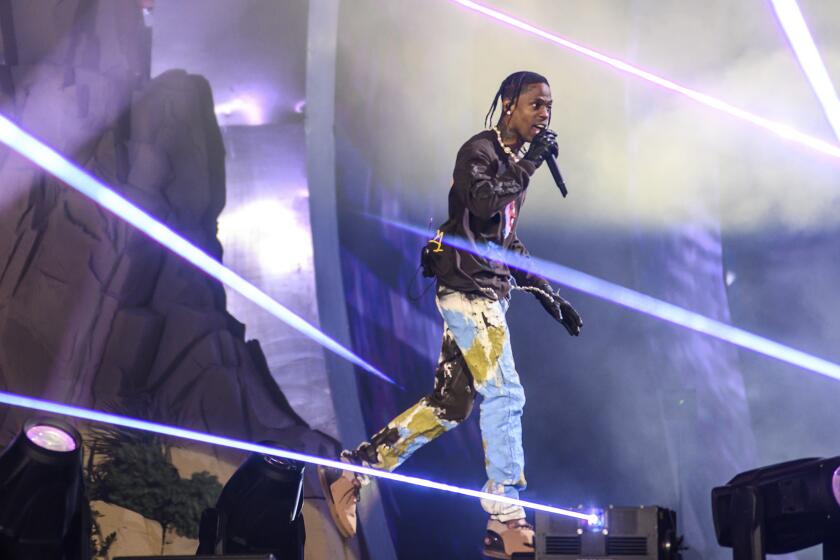

The festival, produced by husband-and-wife team Seak and Brian Smith, will take place Aug. 3 at the John Anson Ford Theatres in Hollywood. The all-day event features a lineup of 15 artists from across the U.S. performing in popular genres from R&B and hip-hop to Khmer balladry and electronic dance music.

Headlining will be L.A.’s own Dengue Fever, whose propulsive blend of psychedelic rock and Khmer song has been filling dance floors around the world for more than a decade. Among the other artists are Bochan, Jay Chan, Phanith Sovann and Khmer Kid.

The festival is billed as a tribute to the pop music heroes — Sinn Sisamouth, Ros Sereysothea and Pen Ran, among others — whose music was the soundtrack to Cambodia’s rapid midcentury modernization. Their mix of Latin grooves, reverberating guitars and sinuous Khmer melodies matched the heady optimism of the era. It was a golden age that all too quickly went dim as political instability mounted in the 1970s.

In pursuit of an agrarian utopia, the Khmer Rouge tried to erase the country’s artistic and intellectual heritage. They almost succeeded. But while the artists didn’t survive, their music still remains. The festival proposes to continue this legacy by featuring contemporary musicians whose original work grows from yet reaches beyond the creative ferment of 1960s Cambodia.

“We wanted to show a variety of talent in different musical genres, that was No. 1,” said co-producer Seak Smith, whose concern was also to select artists who “project a positive message” and whose work is “inspired by traditional music.”

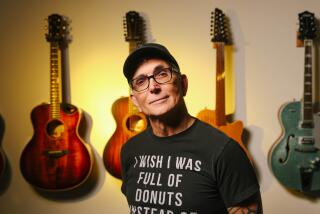

The festival producers are highlighting Dengue Fever because they hope the band’s broad appeal will draw a wider audience for the other artists. Formed in 2001 and drawing inspiration from 1960s and ‘70s Khmer rock, Dengue Fever was the first band to bring Cambodian popular music to mainstream attention in the United States. The group’s Khmer version of Joni Mitchell’s “Both Sides Now,” written for Matt Dillon’s directorial debut “City of Ghosts,” was an early hint of its crossover potential.

Dengue Fever has inspired young artists like Mam, whose career in Khmer music began when she heard its music in college. While she had grown up with the sounds of Cambodian classic rock, Dengue Fever offered something new. “It was the first time I heard Cambodian music remixed in a modern way that was flashy,” she said recently by phone. “I’m very honored to be able to share the stage with them because they are the source of my journey.”

Guitarist Zac Holtzman is happy to talk about the group’s service as cultural ambassadors for the U.S. in Cambodia. But he refuses to see Dengue Fever as limited by nationality or style. “I don’t consider us a Cambodian rock band,” he said over drinks at an Eastside restaurant. Next to him lead songstress Chhom Nimol smiled in apparent agreement. “Nimol is Cambodian, and a lot of our songs are in Khmer,” he said, “but we want to leave our own mark, just like the original artists wanted to do.”

If the goal of the festival is to propel Cambodian music out of the margins, it is also to keep participants’ feet planted firmly on the ground. Besides highlighting an artistic legacy, the event is also the story of a community supporting its own evolution: Six Cambodian-owned businesses are contracted as vendors for the event and the producers will donate 10% of the festival’s net proceeds to the Cambodian Children’s Fund.

PraCh Ly, a Long Beach native and elder statesman of Cambodian hip-hop, was among the first musicians to speak out about the trauma of the Khmer Rouge era. Ly’s debut album, “Dalama: The End’n Is Just the Beginn’n” made him Cambodia’s No. 1-selling hip-hop artist in 2001. But it also fulfilled a desperate need for candor about the war and its devastating legacy.

Fifteen years later, his verses bite as hard as ever, with an unrelenting drive to speak the unspoken and to remember the forgotten. On his forthcoming third solo album, “Dalama 3: Memoirs of the Invisible War,” Ly experiments with darker, more cinematic compositions while venturing deeper into the poetics of war and diaspora. In lieu of his own set, he will take the stage as a featured guest with several artists on the bill.

Cambodian American singer-emcee JL Jupiter’s work is also steeped in memory. But his is remembrance of a personal sort. Jupiter’s music video for “Off Ya Love” — a tight ‘90s-style R&B/hip-hop number produced by Touch of AZI Fellas — honors the family members who paved his way. In it, he holds up an old black-and-white photo of a young man with a guitar. It’s Jupiter’s uncle, a Cambodian rock musician from whom the family believes he inherited his musical talent.

Growing up in Camden, N.J., Jupiter lived on the periphery of the region’s Cambodian community. Although he absorbed Khmer culture from his family, most of his friends were steeped in urban musical culture. “I didn’t have many Cambodian friends growing up,” he said, “hip-hop was my way of being.” Far from alienating Jupiter from his family’s heritage, however, hip-hop brought him closer. “Hip-hop taught me just to be myself,” he said, which for him means balancing the “duality of being an American and a Cambodian.”

There will also be space for those who simply love the music. Indradevi — the brainchild of two non-Cambodian musicians — will perform for the first time as a live band, offering a richly textured mix of jungle, drum and bass, dubstep, industrial rock and Southeast Asian melodies. Formed initially as a DJ duo, Indradevi has gone on to collaborate with numerous Cambodian artists.

Two songs on its recent EP, “Wake from the Poison Dream,” were co-written with Khmer-soul chanteuse Rumany Long. Appearing in elaborate masks as their mythical Indonesian alter egos Barong and Rangda, the duo will share the stage with Long and other special guests.

Laura Mam’s soulful Khmer songs, which she accompanies on guitar, have earned her a sizable audience in her family’s homeland. As frontwoman of the band the Like Me’s, she first came to international attention with a hard-rocking remake of Pen Ran’s “Sva Rom Monkiss” and her own tender ballad “Pka Proheam Rik Popreay.” The songs, released as YouTube videos, earned her band more than 1 million views.

More important to her than numbers, however, are the stories her songs inspire others to tell. One Cambodian American fan, for instance, told Mam that watching the “Sva Rom Monkiss” video with his father, a Khmer Rouge survivor, enabled the two to reconcile a painful past. “The music is going to make you talk,” she said.

Mam sees the festival as an expression of a larger generational shift among Cambodians. “Our parents did everything in their power to survive,” she said, “that was their life mission: to survive, to make it out. So when it comes to our generation, our mission is, I believe, to rebuild.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.