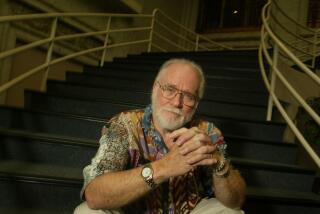

Nicholas King dies at 79; actor helped preserve the Watts Towers

Nicholas King was an actor and an assistant to renowned Hollywood photographer Bob Willoughby in the late 1950s when a close friend of Willoughby stopped by his home with intriguing news.

The friend, film editor William Cartwright, had visited the famed Watts Towers for the first time and was surprised by what he saw.

The unique work of folk art, created over 33 years by Italian immigrant Simon Rodia, had been abandoned since he moved away in 1954. His former house had burned down, the gates to the walled property were open and unguarded, and the grounds were littered with refuse left by unwanted visitors.

King heard Cartwright talking and shared his interest in finding out “why these marvelous towers would be left abandoned,” Cartwright recalled last week.

The two men wound up buying the Watts Towers, which led to the formation of a citizens committee in 1959 to preserve and exhibit the walled complex of spires — the tallest is nearly 100 feet — and other structures decorated with broken pottery, seashells, glazed tiles and pieces of colored glass.

The Watts Towers are now a National Historic Monument that attracts international visitors.

King, who had battled Lewy body dementia in recent years, died April 3 in a nursing home in Santa Rosa, said a son, Silas. He was 79.

“Nick was an artist to the bone; he really was a very sensitive man who understood the international merit of the towers,” said Jeanne Morgan, a charter member and current chair of the Committee for Simon Rodia’s Towers in Watts.

“Without his participation, the towers would have been destroyed under the city’s demolition order” after they were deemed a potential safety hazard in the late 1950s, Morgan said.

Rodia, who has been described as a cement finisher and construction worker, began building the towers in 1921. He stopped working on them in 1954, signed his property over to his neighbor, Louis Sauceda, and moved to Martinez, Calif., to be near relatives.

By talking to people who lived near the towers, King and Cartwright learned that the current owner was Joseph Montoya, a milker in a dairy.

In a 1965 New Yorker story, King recalled that when he and Cartwright met with Montoya for the first time, they asked him if he wanted to sell the towers, “and he said yes — three thousand bucks. We said, ‘Sold.’

“We wrote out a $20 check for the deposit right there, and we walked out of that building 15 feet off the ground. We couldn’t get over it — we owned those damned things.”

Last week, Cartwright told The Times: “We knew we had to do something that we believed should have been done before us: preserving something that needed it and not abandoning it.”

According to the New Yorker article, King and Cartwright cleaned up the area around the towers, and an architect friend of Cartwright soon drew up a plan for a caretaker’s cottage on the property.

But when the architect went to apply for a building permit, he discovered that an order had been issued earlier for Montoya to “demolish and remove the fire-damaged dwelling and dangerous towers from the premises on or before March 5, 1957.”

With the establishment of the Committee for Simon Rodia’s Towers in Watts, Cartwright and King yielded ownership of the towers to the committee, which gave them back what they had paid for the property. The group elected Cartwright as its chairman and he and King as permanent directors.

The Watts Towers avoided the wrecking ball in 1959 after passing a “stress test” in which the tallest spire was subjected to 10,000 pounds of force.

“We couldn’t have done it ourselves,” Cartwright said of the successful effort to save and preserve the towers.

King “developed an intimate friendship” with Rodia, who died in 1965, according to Morgan. Rodia’s American family had called him Sam, and King named his first son Sam Rodia King.

Born Robert Nicholas King in Sacramento on March 21, 1933, he studied acting at the Pasadena Playhouse after graduating from high school in 1951.

He was a regular on the TV version of the radio serial “One Man’s Family,” did stage work and had small roles in films such as “Joy Ride” (1958) and “The Threat” (1960).

King became a partner in a land cooperative on the Garcia River in Point Arena in Northern California, where he moved with his wife, Kate, and their two young children in 1969.

King was involved in logging and started a nursery business in which he grafted apple trees and sold root stocks and apples. He also helped organize the river preservation group Friends of the Garcia and was active in the group Save Our Salmon.

His photographs of a massive storm that struck Point Arena in 1983 were compiled in his book “The Great Disaster at Arena Cove.”

King, who was divorced, is survived by his sons, Sam, Julian and Silas; a daughter, Sarah Bjorg; two brothers, Van and Clint; and three grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.