Barney Rosset dies at 89; publisher fought censorship

Barney Rosset, the renegade founder of Grove Press who fought groundbreaking legal battles against censorship and introduced American readers to such provocative writers as Harold Pinter, Samuel Beckett, Eugene Ionesco and Jean Genet, died Tuesday in New York City. He was 89.

His daughter, Tansey Rosset, said he died after undergoing surgery to replace a heart valve.

In 1951 Rosset bought tiny Grove Press, named after the Greenwich Village street where it was located, and turned it into one of the most influential publishing companies of its time. It championed the writings of a political and literary vanguard that included Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, Tom Stoppard, Octavio Paz, Marguerite Duras, Che Guevara and Malcolm X.

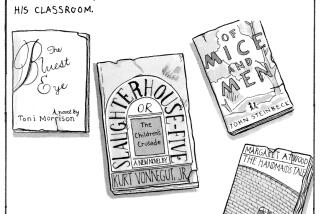

Rosset was best known for taking on American censorship laws in the late 1950s and 1960s, when he successfully battled to print unexpurgated versions of D.H. Lawrence’s “Lady Chatterley’s Lover” and Henry Miller’s “Tropic of Cancer,” both of which were considered far outside the mainstream of American taste but went on to become classics.

In 1959, he published “Lady Chatterley’s Lover,” which had been banned by the postmaster general for promoting “indecent and lascivious thoughts,” but in 1960 a federal appeals court found that its frank descriptions of sexual intercourse did not violate anti-pornography laws.

In 1961, Rosset published “Tropic of Cancer,” which was blocked by more than 60 court cases in 21 states. In a landmark 1964 ruling, however, the U.S. Supreme Court held that it had “redeeming social value” and was thus not obscene.

Rosset “was one of the good guys, in effect doing in book publishing what Playboy was doing in magazines,” Playboy founder Hugh Hefner said Wednesday. “He was breaking the boundaries and published some very important works.”

While running Grove Press, Rosset also founded a seminal literary magazine, Evergreen Review, which published important early works by such writers as Susan Sontag and Edward Albee.

He later branched into film distribution, with his major success the risque Swedish art film “I Am Curious (Yellow),” released in this country in 1968. Although considered mild by today’s standards, the movie, with its scenes of nudity and sexual intercourse, provoked court challenges and feminist ire. But it made millions of dollars for Grove and burnished Rosset’s standing as a countercultural impresario.

“Grove Press and Evergreen were a central part of that cultural revolution of the ‘60s, and Barney was at the center of it,” said Morgan Entrekin, president of Grove/Atlantic, the company formed by the merger of Grove and Atlantic Monthly Press in 1993. “He used to gleefully tell me stories about the FBI files they had on him. He took a joy in standing up to the establishment.”

Rosset’s autobiography, which may be published later this year, is titled “The Subject Was Left-Handed,” a line from a report he found in his FBI file.

The only child of a wealthy banker, Rosset was born in Chicago on May 28, 1922. “I’m half-Jewish and half-Irish and my mother and grandfather spoke Gaelic,” he told the Associated Press in 1998. With that parentage, he once observed, “I was forced into tolerance” and held radical views from an early age. He attended Chicago’s extremely progressive Francis W. Parker School, published a newspaper called Anti-Everything and joined the left-wing American Student Union.

He studied at four colleges, including Swarthmore and UCLA, eventually earning a degree from New York’s New School for Social Research in 1952.

He was a freshman at Swarthmore in 1940 when he bought a banned copy of Miller’s “Tropic of Cancer,” which had been published in Paris in 1934. Rosset identified with Miller’s sense of alienation.

“The sex didn’t really hit me. What really got me,” he told the Voice of America in 2009, “was the anti-American feeling that Miller had. He was not happy living in this country, and he was extremely endowed with the ability to say why.”

After serving in the Army Signal Corps in China during World War II, he moved to New York with his first wife, painter Joan Mitchell, who introduced him to the Greenwich Village art scene. A friend of hers told him about a small press on Grove Street that was for sale. He bought it for $3,000.

He wanted to publish “Tropic of Cancer” but instead began with books that wouldn’t require jumping through legal hoops. His first success was Beckett’s absurdist play “Waiting for Godot” in 1954. He bought it for a $150 advance against a 2.5% royalty and sold more than 1 million copies at $1 each. (It has now sold more than 2.5 million copies.) Rosset named one of his sons after Beckett, who became one of his closest friends.

The year he published “Godot,” Rosset heard from UC Berkeley literature professor Mark Schorer, who urged him to put out an uncensored edition of “Lady Chatterley’s Lover.” Rosset wasn’t enamored of the book, but thought it could pave the way for the much bolder “Tropic,” Miller’s semi-autobiographical account of his early life and sexual adventures in Paris. Rosset notified postal authorities that he was sending the book in the mail. It was immediately confiscated, setting in motion the protracted legal tussle that ended in 1959 with the book’s publication.

He then went to work on Miller, who was loath to allow Rosset to publish “Tropic.” According to Rosset, the author feared what success would do to the book. “He wrote me a letter in which he said…What happens if you publish it and we actually win the case?” Rosset recounted in a 1997 interview with the Paris Review. Miller said he didn’t want it to become so acceptable that it was assigned in colleges “and no one will want to read it!”

Miller’s fear was unfounded. “Tropic” became a classic, along with many other titles Rosset published. He printed Burroughs’ “Naked Lunch” in 1962, and Norman Mailer and Allen Ginsberg were among the defense witnesses at that book’s trial. A few years later, Rosset snatched up “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” (1965) after Doubleday, fearful of repercussions after Malcolm’s assassination, dropped it.

Rosset did not agree with the “socially redeeming” argument that led to the landmark victory for “Tropic” in 1964.

“My grounds has always been that anything should be — can be — published,” he told NPR in 1991. “I think that if you have freedom of speech, you have freedom of speech.”

His attempt to expand Grove into the film distribution business took the company to the brink of ruin. Rosset sold it in 1985 to oil heiress Ann Getty and British publisher George Weidenfeld, who ousted him as Grove’s chief the following year. Rosset found himself starting over at 63 and launched other publishing ventures that eventually ran aground.

He revived Evergreen Review as an online journal and continued to run it until shortly before his death.

Married several times, he is survived by his wife, Astrid Myers, four children, three stepchildren, four grandchildren and four step-grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.