U.S. decision on asylum casts a pall over immigrants fleeing gang violence

Rubilia Sanchez knew she had to flee her hometown of Tecun Uman after gangs repeatedly threatened to rape and murder her.

So she took her four daughters and made the familiar, dangerous trek out of Guatemala, through Mexico and into the United States, where she requested asylum. After waiting for four years, she finally got a date to plead her case to U.S. officials: July 26.

But now, her already hazy future — and that of others fleeing gang violence in Latin America — has been thrust into greater uncertainty.

Atty. Gen. Jeff Sessions ordered immigration judges to stop granting asylum to virtually all those claiming to be victims of domestic or gang violence, a move that could block tens of thousands of people from gaining permanent entry into the U.S.

The gang violence that has raged in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras grew partly from American streets. The most powerful gangs in Central America, MS-13 and 18th Street, were born in Los Angeles a generation ago during the height of the city’s gang wars.

As gang violence exploded in the U.S., authorities responded in the 1990s by deporting gang members en masse to Central America. Experts said the move heightened violence in those countries and prompted waves of terrorized residents to seek refuge in the United States.

Alex Sanchez, a former MS-13 gang member and the executive director of gang prevention and intervention organization Homies Unidos in L.A., said Sessions’ move essentially closes a door to victims of gangs that the U.S. government helped create through past policies.

But supporters of President Trump’s hard-line stance argue that domestic violence and gang problems should be handled by authorities in the immigrants’ home countries.

“The mere fact that a country may have problems effectively policing certain crimes … or that certain populations are more likely to be victims of crime cannot itself establish an asylum claim,” Sessions said. “Asylum was never meant to alleviate all problems — even all serious problems — that people face every day all over the world.”

Amid the Trump administration’s crackdown on illegal immigration, the question of asylum has become an increasingly charged issue. A caravan of asylum seekers from Central America that arrived Tijuana this year — some saying they were fleeing gang violence — made international headlines and became the focus of ire from the president and other anti-illegal immigration forces.

There are no exact statistics on the percentage of asylum seekers who cite gang violence as their reason for coming to the United States. But according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, a backlog of 311,000 asylum claims existed as of late January.

Sessions’ decision is a key part of a broader Trump administration effort to restrict immigration and discourage asylum seekers from coming to this country. The administration has also been separating families detained by immigration agents — including children from parents.

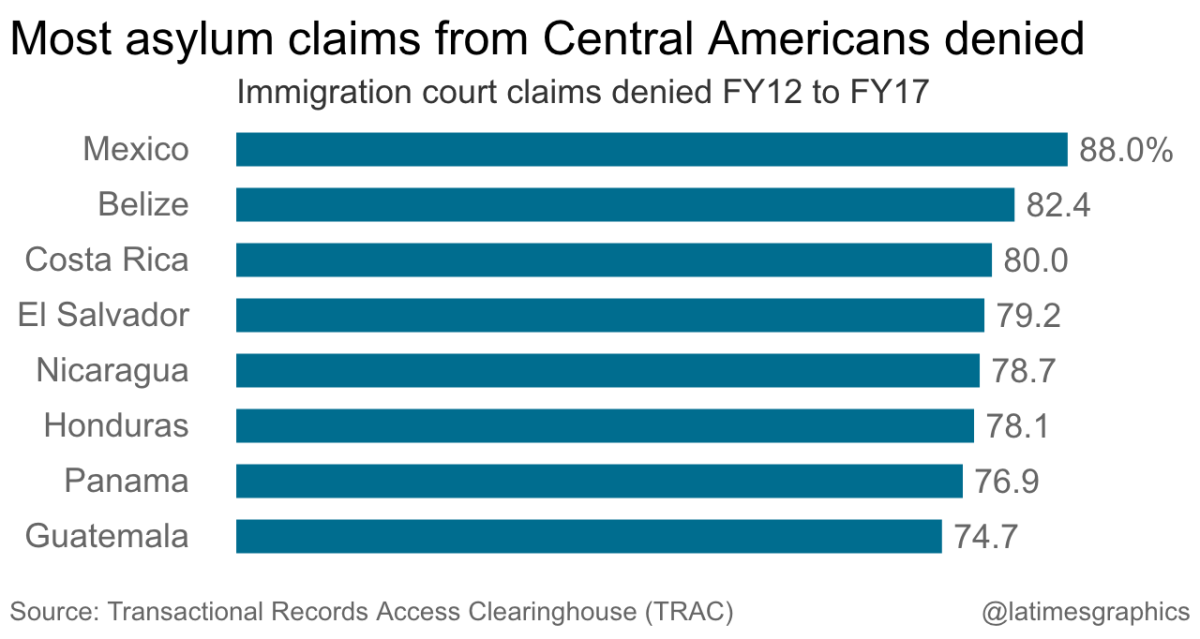

The asylum process has long offered little guarantee of eventual success for immigrants, no matter how desperate the plight.

Between fiscal years 2012 and 2017, immigration judges denied about 75% of the nearly 11,000 asylum cases brought by Guatemalan immigrants, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, a project with Syracuse University that monitors immigration data through public records requests. (The percentage of denials was slightly higher for Salvadoran and Honduran asylum seekers.)

Sessions’ ruling makes it all but impossible for those seeking asylum based on domestic or gang violence to gain permanent entry into the U.S.

“I can’t say our case would have won yesterday or even during the last administration, but … it’s just another attack on Central Americans,” said Rubilia Sanchez’s attorney, Aaron Chenault. “It’s really another example of the culture of this administration — going out of their way to make an already difficult process for these victims of crimes even more difficult.”

There’s been a lot of confusion, a lot of disorder with my case. I’d expect that in Guatemala, but not this country.

— Rubilia Sanchez

Chenault said he’s still hopeful that he will be able to make the case that the Sanchez family deserves immigration relief. He plans to argue that Rubilia and her daughters belong to a particular social group that should be protected, arguing that women and girls are especially vulnerable to gang violence and gang members who often see them as property.

But he acknowledged that it would be harder to prove that the Guatemalan government is condoning the gang’s persecution, which would help in an asylum case under the new policy.

For months, Sanchez had resisted the gang members in her hometown, which straddles the border with Mexico. In December 2013, she said, gang members tried to bust into the home she shared with her daughters. As she braced herself against the door, the men told Sanchez they were going to rape her.

A few days later she ordered her daughters to pack up without telling anyone. For a year, Sanchez, who worked on a banana plantation in Guatemala, and her daughters took refuge in a Mexican shelter run by nuns. She did odd jobs there to make enough money to buy bus tickets to Tijuana.

When the family reached the U.S., Sanchez had a decision to make. They could try to cross illegally or do what international law gave her the right to do and ask for asylum.

She turned herself in at the San Ysidro Port of Entry in 2014 and underwent a “credible fear” interview with an asylum officer. Sanchez and her daughters were allowed to stay in the U.S. as they waited to go before an immigration judge in Los Angeles.

But for four years, Sanchez found herself on the hamster wheel of a deeply backlogged immigration court system.

“There’s been a lot of confusion, a lot of disorder with my case,” she said. “I’d expect that in Guatemala, but not this country.”

But the delays had an upside: They ensured that Sanchez and her girls wouldn’t have to return to Guatemala as long as they were stuck in the bureaucracy.

Sanchez’s husband already had crossed illegally into the U.S. in 2008, intending to send money back to his family. He had planned eventually to return to Guatemala, but Sanchez said the threats from the gang in her hometown forced the family to flee before he could.

The family settled in a run-down 500-square-foot studio apartment near MacArthur Park. Their living room doubles as a bedroom and dining room. The children share bunk beds. The couple sleep on separate couches.

Sanchez works at a clothing factory after the government granted her a work permit; her husband is paid under the table in construction.

After years in the U.S., their four oldest daughters — 11, 12, 14 and 17 — all think like Americans. They speak flawless English. The couple have a fifth child, a 2-year-old born in the U.S.

Despite this week’s decision, Sanchez said, she’s determined to remain optimistic. A devout Christian, she reasons that she followed the law and refuses to believe that her family will have to go back to a place that feels more like a deathtrap than home.

“For God, nothing is impossible,” Sanchez said. “Everything will be fine. God is just.”

The most immediate effect of Sessions’ decision will likely be felt by asylum seekers at the border.

When people arrive with an asylum claim, they typically meet with a U.S. official, who screens them to determine whether the fear of returning to their home country is credible.

Sessions’ decision sent a clear message that requests based on fleeing gang or domestic violence are to be rejected.

In Tijuana, Honduran immigrant Synthia Savllon and her 1-year-old son, Jonathan, are awaiting their turn to meet with border officials and plead for asylum.

The 19-year-old, who signed up two weeks ago at the San Ysidro Port of Entry for a chance to be heard, said she was orphaned as a child and grew up on the streets. When she was 15, she met a man who would become her boyfriend. He gave her a roof over her head, she said, but she soon discovered that he was a drug addict and gang member.

Savllon said he regularly beat her and threatened her life. She said she had three children with the man but only managed to escape with her youngest, leaving behind 2- and 3-year-old daughters.

Savllon’s chances of getting asylum were already slim because she has no family in the U.S. The attorney general’s decision all but eliminated her odds of even getting a hearing.

But Savllon said she had no plans of returning to Honduras, fearing she would be killed by her boyfriend. She reasoned that staying in Mexico posed its own dangers, so Savllon said she was determined to try to seek asylum in the U.S., despite the grim odds.

cindy.carcamo@latimes.com | Twitter: @theCindyCarcamo

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.