California’s deadly hepatitis A outbreak could last years, official says

Health officials said Oct. 5 that the outbreak could continue for many months, even years. (Oct. 6, 2017)

California’s outbreak of

At least 569 people have been infected and 17 have died of the virus since November in San Diego, Santa Cruz and Los Angeles counties, where local outbreaks have been declared.

Dr. Monique Foster, a medical epidemiologist with the Division of Viral Hepatitis at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, told reporters Thursday that California’s outbreak could linger even with the right prevention efforts.

“It’s not unusual for them to last quite some time — usually over a year, one to two years,” Foster said.

That forecast has worried health officials across the state, even in regions where there haven’t yet been cases.

Many are beginning to offer vaccines to their homeless populations, which are considered most at risk. Doctors say that people with hepatitis A could travel and unknowingly infect people in a new community, creating more outbreaks.

San Diego, Santa Cruz and L.A.

San Diego County declared a public health emergency in September because of its hepatitis A outbreak.

Since November, 481 people there have fallen ill, including 17 who died, according to Dr. Eric McDonald with the county’s health department. An additional 57 cases are under investigation, he said.

Hepatitis A outbreak

- 481 cases in San Diego County

- 70 cases in Santa Cruz County

- 12 cases in L.A. County

- 6 cases elsewhere in the state

Sources: County health departments, California public health departments

Hepatitis A is commonly transmitted through contaminated food. The only outbreak in the last 20 years bigger than California’s occurred in Pennsylvania in 2003, when more than 900 people were infected after eating contaminated green onions at a restaurant.

California’s outbreak, however, is spreading from person to person, mostly among the homeless community.

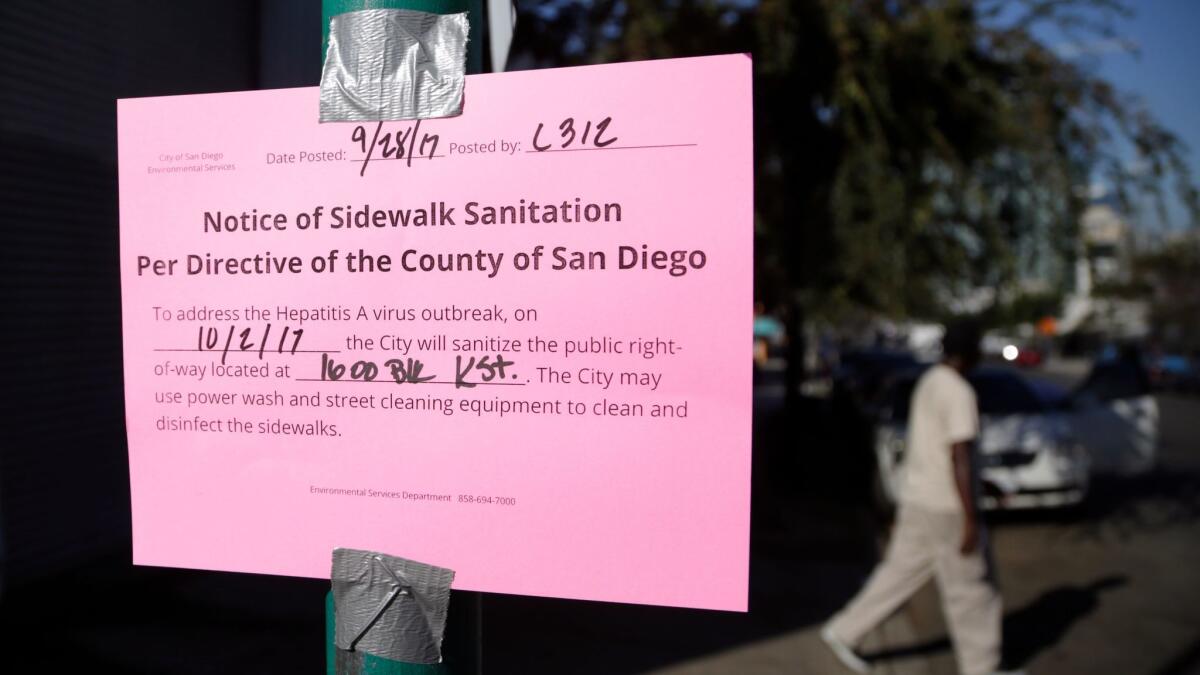

The virus is transmitted from feces to mouth, so unsanitary conditions make it more likely to spread. The city of San Diego has installed dozens of handwashing stations and begun cleaning streets with bleach-spiked water in recent weeks.

McDonald said county health workers have vaccinated 57,000 people in the county who are either homeless, drug users or people in close contact with either group.

“The general population — if you’re not in one of those specific risk groups — is at very low risk, and we’re not recommending vaccinations,” he said.

The outbreak has also made its way to Santa Cruz and L.A. counties, where 70 and 12 people have been diagnosed, respectively.

Officials from both counties say they’ve vaccinated thousands of homeless people and will continue to do so.

New cases linked to the outbreak might not appear for weeks, because it can take up to 50 days for an infected person to show symptoms, said Santa Cruz public health manager Jessica Randolph.

“I don’t think the worst is over,” Randolph said.

Where next?

Tenderloin Health Services, a clinic in the San Francisco neighborhood known for its large homeless population, has been offering hepatitis A vaccines to its patients for weeks. The clinic recently held an event in which workers gave shots to 80 people in three hours, said Dr. Andrew Desruisseau, the clinic’s medical director.

“The cases in San Diego and the magnitude of the epidemic there certainly set off alarms in the Bay Area,” he said. So far, there have been 13 hepatitis A cases in San Francisco, but none associated with the outbreak.

Desruisseau said 90% of the clinic’s patients are homeless and many also have other liver problems or are drug users, making the disease especially dangerous.

Typically, only 1 out of every 100 people with hepatitis A dies from the disease, but it appears to have killed a higher rate of people in San Diego because of the population affected, experts say.

All 17 people who have died in the San Diego outbreak had underlying health conditions, including 16 who had liver problems such as hepatitis B or C, McDonald said.

Desruisseau said he was particularly concerned about conditions on the streets in San Francisco.

“With all of the housing crisis and gentrification in San Francisco, we’re seeing a much more condensed homeless population,” he said. “We have a lot of obstacles in keeping it a very sanitary place for our clients.”

Doctors and nurses in several California counties are beginning to offer vaccines to their homeless populations, as recommended by the state health department. Typically only children and people at high risk are vaccinated for hepatitis A.

In Orange County, which has had two hepatitis A cases linked to the outbreak, public health workers have given out 492 vaccines, mostly to homeless people, officials said. County nurses have also been visiting shelters and parks to vaccinate people.

Some officials, including in Riverside and Sacramento counties, also said they were reviewing their sanitation protocols for homeless encampments. An L.A. councilman recently called for more toilets in neighborhoods such as skid row and Venice in light of the local hepatitis cases.

Many have blamed San Diego’s outbreak on a lack of public bathrooms near homeless encampments.

In Oakland, city workers, represented by SEIU Local 1021, sent a letter to City Hall last month saying they feared a hepatitis A outbreak in the region’s homeless community. So far, there haven’t been any cases in Oakland or the rest of Alameda County, but city safety steward Brian Clay said he believed the city has allowed unsanitary conditions in homeless encampments.

Oakland city officials did not respond to a request for comment.

“There’s syringes, there’s human feces, there are dead animals, rats alive, and dead rats … pee bottles, five-gallon buckets used as toilets,” Clay said. “We’re definitely concerned about this added threat of hepatitis A.”

soumya.karlamangla@latimes.com

Twitter: @skarlamangla

ALSO

To slow deadly hepatitis outbreak, paramedics will now provide vaccinations to the homeless

UPDATES:

3:30 p.m.: This article was updated with additional details about the outbreak.

This article was originally published at 12:10 p.m.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.