L.A.’s new tallest building is poised to become a lightsaber with massive LED displays

Angelenos watched it rise in the downtown skyline for months. (June 26, 2017)

Nearly a fifth of a mile up in the sky atop Los Angeles’ tallest building, two massive LED displays — each 42 by 60 feet — sit dormant, ready to beam messages out across the city.

The screens consist of 250 million pixels, each no bigger than a pea, ready to explode with vibrant oranges, blues and greens once the sun sets and the building begins to glow.

Skyscrapers have been called the “sword of cities.” But the Wilshire Grand is more of a lightsaber. In addition to the lighted top, the building itself is covered in roughly 2.5 miles of LEDs running up and down the building’s spine.

All this lighting is a first for an L.A. skyscraper, and it will make the Wilshire Grand — for better or worse — stand out in downtown’s skyline perhaps even more than its height.

In the last decade or so, LED lighting has become an essential part of the urban landscape, with architects and building owners using the technology to make their tower pop and to highlight the architectural elements at night.

The owners of the

LEDs are even more common on the skylines of Asian cities, flashing with a rainbow of colors and images at night.

“In Asia, they just like a lot of bling, color and motion,” said Jim Anderson, an executive at Philips Lighting, which worked on the Empire State Building. “That’s what they want. They want to create excitement. In [the] U.S., they’re looking for a more planned and sophisticated approach.”

The LED boom is hitting California’s two most prominent cities at the same time. In San Francisco, workers are putting the finishing touches on that city’s new tallest building, the 61-story Salesforce Tower. An artist is developing a different type of lighting display to crown that building.

All this flash does not come without debate.

In 2011, the Los Angeles City Council approved a plan that made the Wilshire Grand the anchor of a sign district along the Figueroa Corridor. The district will allow buildings in the area to have LED displays, including some that show advertising. Backers argued that these elaborate advertisements would bring an energy and vibrancy to the area, citing places like Tokyo and New York’s Times Square.

But others see them as visual junk. Opponents sued to try to block some of the LED signs, claiming the images would inundate the public and, in some cases, distract motorists. But the courts allowed the sign district to move forward.

The top of the Wilshire Grand will flash the logo for Korean Airlines, which owns the building, and the InterContinental Hotel, a key tenant. A street-level sign will bathe drivers and pedestrians on Figueroa Street in static advertisements.

Other downtown towers use some distinctive lighting, most notably the U.S. Bank Tower, whose crown is often lighted with specific colors to celebrate milestones and sports victories. But that's nothing compared with the wattage of the Wilshire Grand.

This LED boom has been driven at least in part by an influx of Asian developers, said Paul Tang, a Los Angeles architect whose firm has a large presence in China. He recently moved back from Shanghai.

When working with lighting designers in China, Tang said their paramount concern was not how the interior of the building was illuminated but how the outside was lighted.

“They could care less about the lighting ambiance but instead how it’s perceived to the general public,” Tang said.

“Downtown L.A. is absolutely different from the downtown L.A. I left in 2010. It’s a whole different perspective on living in an urban scenario that’s completely foreign to California, where everyone wanted their dream home in suburbia,” he said.

The view from the top

Within the Wilshire Grand’s rooftop sail, Brad Gwinn and James Hart took stock of their company’s creation.

Gwinn and Hart, who work for the lighting design firm StandardVision, have been laboring for several years to make the Wilshire Grand’s LED dreams a reality.

When the project was first proposed eight years ago, the

“In 2009, if you look back, there’s not a lot of examples of buildings with this type of lighting,” said Gwinn, who is StandardVision’s chief operating officer, adding that his company’s first project using LEDs like this was in Macau that year.

The initial designs of the Wilshire Grand included a room where a host of computers could be used to manipulate the building’s lights.

Now it’s all done from an app, Gwinn said, holding up his white iPhone. From this app, Gwinn’s team can control the brightness of the displays. When the sun is still out, they need to blast the brightness for the LEDs to be visible, he said.

“You can never compete with the sun on a glass building,” Gwinn said while standing on a roof deck and squinting upward.

“There’s this rush for brighter, but if the screen looks like paper, that’s better.”

Opponents of the Wilshire Grand argued that the screens and lights would distract drivers on the various freeways that descend on downtown.

That was 2011. Now the screens most likely to distract drivers are in the cars with them, Gwinn says.

Angelenos got their first real taste of what’s to come early last month when the building was festooned with the colors of the 2024 L.A. Olympic bid. Buildings across the city joined in, and by happenstance the Wilshire Grand needed to test the lighting systems, building spokeswoman Lisa Gritzner said.

“The city reached out to us and said, ‘Hey we’re lighting all these iconic buildings’ and asked if we were willing and able,” she said.

“We needed to test the lights anyway. So it was really fun.”

Imagine when the Lakers win another

“We want to be able to use it it like the Empire State Building — as a symbol of L.A. pride,” she added.

The Salesforce Tower

As the Wilshire Grand is altering L.A.’s skyline, the Salesforce Tower is altering San Francisco’s.

The city requires developers to spend 1% of the cost of any major downtown project on public art. That’s how artist Jim Campbell came to create an LED light installation on the top nine floors of the tower, which is slated to be the second tallest building in California.

This piece is less about branding when compared with the Wilshire Grand. Campbell said he hopes his project will be an alternative to the “visual barrage” of some LED skylines. He added that after looking at some of the tests of the Wilshire Grand’s lights, he thought “it’s kind of sad.”

“You look at a lot of the buildings in places like Hong Kong,” he said. “It looks like the system is in demo mode, which means it’s playing color spectrum…. It seems like there are too many buildings that are doing too much with light.”

Campbell is still very much in the planning stage, but he knows the LEDs will not be pointing out into the city, but rather inward. The light will bounce off the aluminum. Renderings that were submitted to the San Francisco City Planning Commission show lights that are less intense.

“This process of reflecting the light off of the surface...creates a soft and continuous image instead of a harsh direct image like a Times Square video screen,” Campbell wrote in his artistic statement submitted to the Planning Commission.

In an interview, Campbell explained that about a third of the way into the building’s construction, developer Boston Properties asked if it would be possible to light up the building in, say, blue during the Salesforce convention—as an advertisement for the company.

He blanched at the idea.

“I finally convinced them that no artist would do that,” he said. “If you want to go do that model then I’m not designing this unique standalone thing. I told them you should just build your own light system and then hire me to do temporary work.”

This episode underscores the push and pull between the desire to turn these buildings into icons of civic pride and the marketing allure of these towering billboards.

The billboard corridor

Back at the Wilshire Grand and slightly closer to the ground, Gwinn and Hart wandered through the tower’s halls with the building’s senior designer, Tammy Jow. They reminisced about fighting over elevators and marveled that the building’s air conditioning had been turned on.

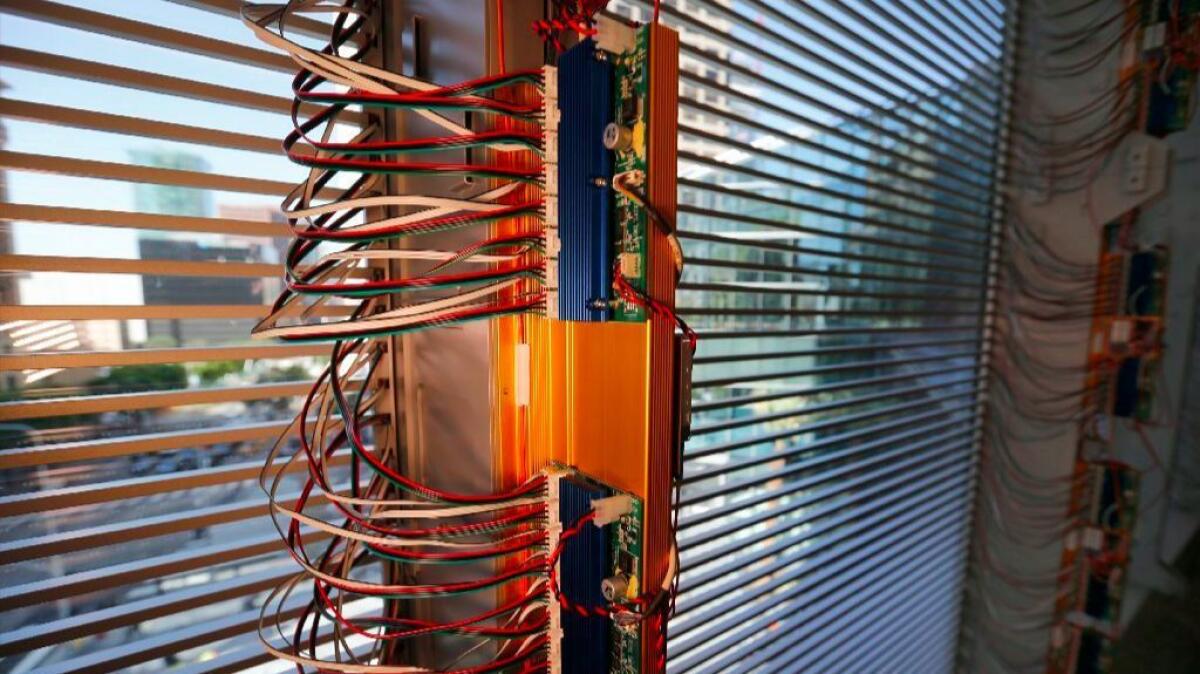

They roam into a conference room on the fifth floor. It looked as if the shades were pulled down and sunlight was pouring through the blinds. Except they aren’t blinds, they are LED light panels that make up a three-story-high digital billboard.

When it lights up, the billboard will offer an effervescent glow of ads.

Now, Gwinn said, the challenge will be to find content that can be shown on a screen that’s 115 feet long and 45 feet tall.

“It’s not like you can get an 8K video right off the shelf,” Gwinn said — referencing the high-resolution videos that are in vogue these days.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.