Mexicans stage ‘A Day Without Journalism’ to protest deadly attacks on the news media

Several prominent Mexican news outlets went dark Tuesday to protest the murder of journalists across the country, including Monday’s brazen midday killing of veteran crime reporter Javier Valdez.

The “Day Without Journalism” protests were staged by publications across Mexico, where at least five journalists have been gunned down this year and where few perpetrators are ever brought to justice.

On Tuesday, reports emerged of yet another attack, this time against a magazine executive in the state of Jalisco.

Sonia Cordova, an executive at the weekly Semanario Costeno and the wife of the magazine’s publisher, was wounded and her 26-year-old son killed Monday night when a gunman besieged them in the city of Autlan, the state prosecutor’s office said. Cordova remained hospitalized, the office said.

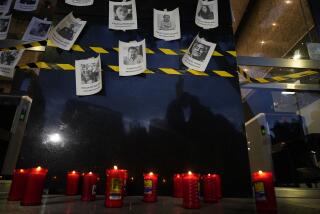

“In Mexico, journalists are killed because they can be, because nothing happens,” read the text Tuesday on the home page of Animal Politico, one of Mexico’s most influential online news publications. Instead of its normal content, the site published a black Web page featuring photos of Valdez and other journalists killed this year. Several other major news outlets did the same.

In Mexico City on Monday night, journalists marched in the streets and scrawled “In Mexico they are killing us” in front of the Angel of Independence monument. Vigils were planned in several states on Tuesday evening.

Since 2000, at least 125 journalists have been killed in Mexico, according to the National Human Rights Commission, the government’s independent watchdog.

The deadly risks of reporting on drug cartels or government corruption have led many publications to self-censor and others to shut down. Reporters who continue to pursue hard-hitting stories often must employ bodyguards or take other extraordinary security measures.

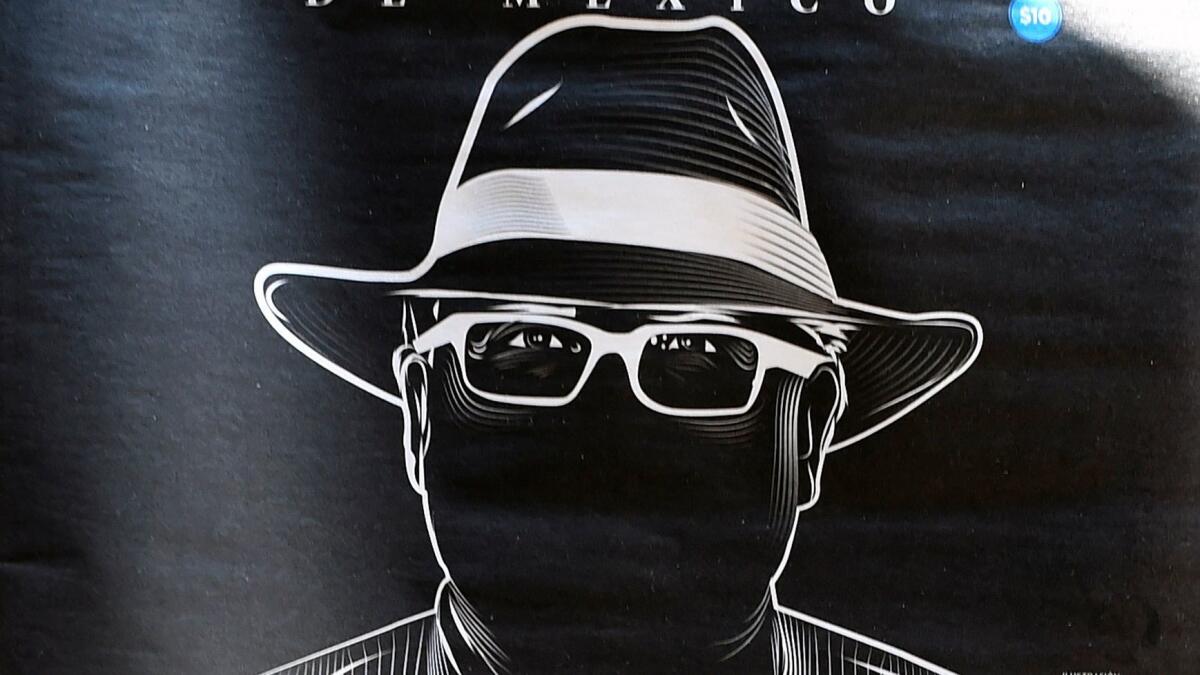

The death of Valdez, who had been internationally recognized for his work and who last year published a book about the challenges of practicing what he called “narco-journalism,” sent shock waves through Mexico’s media community.

Valdez, a correspondent for the Mexico City-based daily La Jornada and a co-founder of the regional weekly Riodoce, was shot dead on a busy road in broad daylight in the city of Culiacan.

Alejandro Sicairos, a co-founder of Riodoce, said in a radio interview Tuesday that he is sure that organized crime ordered the attack, dismissing a suggestion by a local prosecutor that Valdez may have been killed in an attempted carjacking.

“We don’t know who ordered it and who carried it out, but we do know that organized crime is directly responsible for this,” Sicairos said.

He said Valdez died because he had tirelessly documented rising violence in the state of Sinaloa, where the sons of Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman have been fighting other groups for control of the Sinaloa drug cartel in the months since Guzman, the cartel’s founder, was extradited to the United States.

The bloody conflict has helped drive violence across Mexico, which is on track to record more homicides in 2017 than any year since the government began releasing such statistics in 1997.

There is unstoppable violence in Sinaloa. Journalism is in the middle of this crossfire.

— Alejandro Sicairos, co-founder of Riodoce

“There is unstoppable violence in Sinaloa,” Sicairos said. “Journalism is in the middle of this crossfire.”

In the interview, Sicairos pleaded with the leaders of organized crime to respect journalists’ role as messengers of information. “We give accounts of events, but we have nothing to do with them,” he said.

Tania Montalvo, the editor of Animal Politico, said journalists in her newsroom decided Monday afternoon to stage a Day Without Journalism protest after they learned of Valdez’s death.

“It was a moment to do something, to say, ‘Enough is enough,’” she said.

Montalvo said Tuesday’s protest was “a call to our readers to act” and an attempt to pressure authorities to do more to protect the media. An attack against a journalist, she said, is “also an attack against citizens and their rights to free information.”

“Every time a journalist is killed there are tweets condemning the attack, but nothing happens,” she said.

Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto, who has been criticized for not speaking out more forcefully after other journalists were slain, sent a Twitter message Monday denouncing the killing of Valdez: “I reiterate our commitment to freedom of expression and press, fundamental to our democracy.”

But media advocates say authorities are not doing nearly enough to protect freedom of expression in Mexico, which last year was named by Reporters Without Borders as the third-most deadly country in the world for journalists, after Syria and Afghanistan.

Although there is a special prosecutor devoted to investigating crimes against journalists as well as a program established in 2012 that provides emergency evacuations and police protection to members of the media who have come under threat, violence against journalists is getting worse, advocates say.

Article 19, a nonprofit that advocates for media protections in Mexico, recorded a record 426 threats or attacks against the press last year, including beatings and torture, said Luis Knapp, an attorney with the group.

In more than 99% of those cases, he said, the perpetrators were never prosecuted.

Twitter: @katelinthicum

Cecilia Sanchez in The Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

ALSO

What it’s like to report in one of the world’s deadliest places for journalists

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.