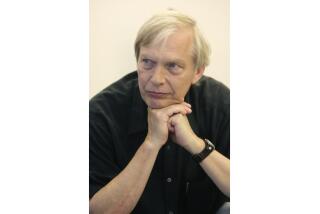

Robert W. Taylor, a pioneer of the modern computer, dies at 85

Robert W. Taylor, one of the most important figures in the creation of the modern computer and the Internet, has died. He was 85.

According to his son Kurt Taylor, the scientist died Thursday at his home in Woodside. He suffered from Parkinson’s disease and other ailments.

Taylor’s name was not known to the public, but it was a byword in computer science and networking, where he was a key innovator who transformed the world of technology.

Taylor was a Pentagon researcher in the 1960s when he launched Arpanet, which evolved into what we know today as the Internet.

Later, he moved to Xerox’s legendary Palo Alto Research Center, where he oversaw the engineering team responsible for such inventions as the personal computer, Ethernet and the visual computer display.

Taylor pushed for his projects with outspoken, uncompromising vision. Along the way, he fought his share of bureaucratic battles.

The adopted son of a Methodist minister and his wife landed at the Pentagon in the mid-1960s after a stint with NASA.

He worked at the Advanced Projects Research Agency, or ARPA, and was responsible for a project devoted to interactive computing.

With millions of dollars at his disposal, Taylor funded nascent computer-science programs at institutions around the country — MIT, UCLA, Stanford, the universities of Utah and Illinois.

He nurtured the youngest, most talented scientists he could find.

But it irked him to have to deal with their myriad incompatible computer systems. He demanded a system that would allow them to communicate with each other and secured the funding to get the concept off the ground.

He then oversaw the construction of a network that seamlessly connected numerous research computers nationwide.

Taylor foresaw that this network would one day not only be an administrative tool, but a necessary utility for the public.

In a 1968 paper he co-wrote, Taylor stated: “In a few years, men will be able to communicate more effectively through a machine than face to face.”

He predicted that the network would provide services people would come to rely on, such as investment advice, and others that you would “call for when you need them,” like dictionaries and encyclopedias.

In 1970, Taylor moved to the Xerox Corp. after ARPA moved away from basic research and become more devoted to Vietnam War needs.

There, the native of Texas became intrigued by Xerox’s research on the West Coast to develop technologies for the “paperless” or digital office.

Taylor assembled an impressive team of computer designers, in part by raiding the academic programs he had funded at ARPA.

Computers of that era were room-sized machines that worked on a time-sharing basis — every user competed for time on the machine to run his or her own programs.

Taylor’s concept, and those of the scientists he brought in, was that the computer should be a personal device with a high-quality display.

Under his guidance, scientists Alan Kay, Butler Lampson and Chuck Thacker designed and built the first personal computer, the Alto.

It was equipped with a screen about the size and shape of a paper page, and in time it sported a graphical display that eventually would become familiar via its offspring, Microsoft Windows and Apple’s Macintosh screens.

The Alto was a genuinely personal device — every PARC computer scientist had his or her own. It began to have the electronic power to fulfill Kay’s dream of a computer that could not only perform calculations, but advance human creativity.

Taylor’s lab also developed Ethernet and a what-you-see-is-what-you-get word-processing program called Bravo — which, after its developer, Charles Simonyi, moved to Microsoft, evolved into Microsoft Word.

Taylor’s greatest achievement may have been creating an environment that allowed his diverse, brilliant engineers and scientists to work together.

He nurtured their talents and teamwork while fending off more mundane corporate demands.

In addition to Kurt, Taylor is survived by two other sons, Erik and Derek, and three grandchildren.

esmeralda.bermudez@latimes.com

ALSO

A new boss ponders the past and future of the fabled Xerox PARC

To compete with Silicon Valley for engineers, aerospace firms start recruitment in pre-kindergarten

UPDATES:

10:40 p.m.: This article was updated with more information on Taylor’s life and career.

This article was originally published at 9:35 p.m.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.