POETRY IN MOTION

Thirty years ago Ronnie Knox was a controversial football star whose stepfather, Harvey, was treading new ground as his agent. But Ronnie didn’t turn out the way everyone in the world of sports expected. He has resurfaced as a wandering poet.

Thirty-odd years ago when Ronnie and Harvey Knox were trouping about the Los Angeles area as if they owned it, a busy lawyer named Jerry Giesler had the best-paying law practice in town.

A photo gallery of Giesler’s clients was always on the walls of his outer office, and he took pains to arrange their faces in the order of their distinction, with Clark Gable usually No. 1, Jean Harlow No. 2, Errol Flynn No. 3 and Robert Taylor No. 4.

But nothing lasts forever. Needing a lawyer one day, Harvey Knox looked up Giesler. And in Giesler’s gallery a week or so later, Ronnie was No. 1, Harvey No. 2, Gable No. 3 and Harlow No. 4.

“And nobody was the least bit surprised,” Harvey said here the other day.

In the 1950s, from one year to the next, the Knox entry was probably the most prominent in California sports:

--Ronnie, an uncommonly gifted football player, threw the ball with more precision and power than almost any other passer of his or any other day.

--Harvey, his stepfather, was football’s first agent and a flamboyant eccentric who first surfaced publicly in 1950, when Ronnie was 15.

“I got a fast start (in 1950-51-52),” said Harvey, who sent the boy to three high schools in three years--Beverly Hills, Inglewood, and Santa Monica. As a prep star, Ronnie was CIF player of the year in 1952. And as a college star in 1955, after a big freshman year at California, he helped UCLA get into the Rose Bowl and then turned professional, passing up his senior season.

By the end of the decade, setting a North American record that still stands, Harvey had arranged for his stepson to play on 10 football teams in precisely 10 years, including four Canadian teams.

Never playing longer than a year anywhere, Ronnie drifted from Santa Monica, Berkeley and Westwood to Canada, then down to the Chicago Bears and back to Canada, where he retired from football in 1959. As the United States’ youngest retiree, he turned 24 that year. And suddenly dropped from sight.

He has been out of sight ever since--for the better part of 30 years.

Where has he been? And what is he up to now?

Well, he’s still on the move. At 53, he is now in the 39th year of his career as a drifter, the life he began as a high school sophomore.

When a reporter found him in the San Fernando Valley the other day, Ronnie, preparing to hit the road again, was just moving out of a one-room apartment in Canoga Park, where he had lived for a couple of weeks. In the last three decades, he has lived up and down this state, from McKinleyville to San Francisco, Malibu and Mexico, and in several other states--Texas, for instance, and Maine--as well as Europe.

All the while he has spent more time writing poetry than doing anything else. Stretched out on his cot or in his beaten-up, 12-year-old car, he also reads English literature by the hour or studies about the life at sea for which he often wishes.

Over the years, in one guise or another, Ronnie has held a variety of part-time jobs ranging from film and TV acting to football coaching to kitchen work on a San Francisco harbor boat.

“Stay free, that’s my philosophy,” he said softly one noon in Northridge at his favorite Greek restaurant, where he looked fit, youthful and nicely groomed. “The trick is to stay fluid without turning into H2O.”

Asked to sum up the three decades that he has been out of football, Ronnie, who has been single since a 1964 divorce, smiled and said: “Like James Fenimore Cooper’s noble savage, I’ve been away.”

Harvey has been away, too. An entrepreneurial free spirit, once a prosperous haberdasher on Beverly Hills’ Rodeo Drive, Harvey has become a dealer in ocean-front real estate.

He is already on the map in his new hometown, McKinleyville, a beach town in the redwoods 300 miles north of San Francisco. The official city map points the way to Knox Cove, which he founded several years ago. There, Harvey and his partners have built a number of large, strange European-type stone castles overlooking the Pacific, and, there, they are offering 26 ocean-side lots at $60,000 to $80,000 each.

They will build another stone castle for you at your choice of lots, if you want, or you can build something of your own.

A white-haired dynamo with a sporty white mustache, Harvey said he has made and lost five or six fortunes in his 79 years. He added that he is on his way to the one he intends to keep.

He insisted that he has no regrets about the bizarre football era of the Knoxes. “Ronnie could have been the best (football player) of all time, but that was long ago,” Harvey said. “It’s all over now.

“I just want him to be happy. He’s had a few emotional problems, you know, and I’ve sent him money when I had it. I love him. I love all my children, and they love me.”

He expects to see Ronnie in McKinleyville again any day now. One evening, his eyes absently fixed on the clouded, sinking sun in the Pacific, Harvey said: “Ronnie gets around.”

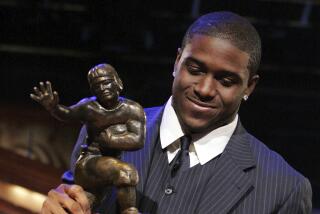

RONNIE THEN

On Sept. 16, 1955, on the night of Ronnie’s UCLA debut, the opponent was Texas A&M;, then coached by Bear Bryant, who was at least as conservative as the Bruin coach, Red Sanders.

So hardly anyone foresaw the explosion that rocked the Coliseum when Ronnie trotted in and astonishingly threw eight passes. Of these, six were completed, three for touchdowns, as UCLA won, 21-0.

Bryant, afterward, chose to ignore all that. Characteristically, he said: “Our guys hung in there pretty good, didn’t they?”

The same night, however, Sanders said: “Never have I seen a cooler man back there than Ronnie.”

Only rarely indeed, before or since, has any young athlete matched the impact that Ronnie made on California football in the ‘50s. He had both the talent and size--195 pounds, 6 feet 1 1/2 inches--for stardom at both of his positions, T-formation quarterback and, under Sanders, single-wing tailback. And in his biggest games, he maximized what he had.

Thus in 1952, en route to CIF player of the year recognition, he completed 65% of 192 passes, throwing a record 27 times for touchdowns, as Santa Monica won the championship.

College freshmen in those days were ineligible for varsity competition. So at Cal in ‘53, playing for a school that was routinely stomped on by Stanford, Ronnie led the Bear freshmen to an upset win over the Stanford frosh, 19-12.

That day, in his last Berkeley start, Ronnie threw for all 3 touchdowns, completed 12 of 17 passes, returned 3 kickoffs for 93 yards, averaged 44 yards punting, and, in the age of one-platoon football, also starred on defense.

“Ronnie Knox was an unbelievable talent,” said Sid Gillman, the Hall of Fame coach. “The way he could run and throw the ball, he was the John Elway of his time.”

Sanders was to call him “the greatest tailback I ever had,” although Ronnie played for him only one season before opting for Canada in 1956.

Others considered that leadership and football intelligence were Ronnie’s most distinctive qualities.

Said Harvey: “His natural father was Dr. Raoul Landry, a college professor and physicist who helped split the atom at Chicago in World War II. Ronnie has that kind of brain.”

Sadly, however, this led to his downfall as a football player. Or so it seemed. The consensus of those who knew him best 30 years ago was that Ronnie was ruined as a football player by two things--his raging impatience with the intellectual shortcomings of his coaches and his bad luck in getting the particular coaches he had.

He was a born T-formation quarterback who would have flourished under the emerging T-formation giants of his day--Gillman, Frank Leahy or Paul Brown. Instead, he came under some of the least imaginative coaches of an old-fashioned, dying era--Cal’s Pappy Waldorf, Canada’s Jim Trimble, Paddy Driscoll of the Chicago Bears and seven or eight others in that mold.

At UCLA he played for a winner--but in the Sanders system in the ‘50s, great passers were tolerated only if they could also run, block and tackle.

Impatiently, angrily, Ronnie gave up on every coach he ever had except one, the late Jim Sutherland, his high school coach at Santa Monica. And, searching for geniuses who believed in him--and believed in modern football--he wandered from town to town.

It was to become a habit.

RONNIE NOW

The end for Harvey’s boy as an athlete came in Canada in September, 1959. After football practice one night that year, Ronnie walked out on the Toronto Argonauts, flew home to write poetry, and, in a frank and revealing statement, told the Associated Press:

“I just had enough. Money isn’t everything, and I’m sick to the teeth of (football). It’s a game for animals and I like to think I’m above that.”

As a Toronto quarterback, Ronnie had been making $1,250 a week, about as good as you could get in pro football then--and he left with half the season left. That is, he walked out on about $12,000--which might not have been an entirely rational thing to do, considering that poetry can be written in football’s six-month off-season.

Nor, some would say, was he behaving rationally a few months later when he rejected an invitation from Leahy and Gillman to become the San Diego Chargers’ first quarterback in 1960, the season they played in Los Angeles.

“We couldn’t even find him at first,” said Gillman. “It took us six weeks to track him down. He was living in a dump at the beach, and when we got out there, some woman came to the door and said Ronnie wouldn’t talk to us.”

The woman was Viennese artist Renate Drucks, who had married Ronnie the year before. They parted 24 years ago.

In 1960, Leahy, after a successful tour at Notre Dame, was serving as the Chargers’ first general manager, and in time he got through to the player he called the best young quarterback in the game.

“Mr. Leahy was a gentleman,” Ronnie recalled one afternoon at the apartment he had in Canoga Park. “He told me that the Chargers were owned by a wealthy hotel man named Barron Hilton, and he told me that I could name my own salary. Just pick a number, he said. I said, ‘No, thanks, I’ve given up football.’ ”

Ronnie was 25 at the time.

Talking about it now, he smiles wanly. He is dressed for dinner out in jeans, a long-sleeved sport shirt and a pair of expensive black dress shoes. To Times writer Cecil Smith 34 years ago, Ronnie was “a big, rangy kid, handsome, with tousled brown hair and hazel eyes, an easy, relaxed manner and a great deal of physical charm.” And most of that still goes. Ronnie’s weight and hair are almost unchanged today, although, like many old quarterbacks, he is noticeably round-shouldered.

Ronnie describes his basic nature as young-spirited, “even clownish.” But on one subject he remains dead serious.

“I was deep into literature,” he said of the years when he was growing tired of football. “And I finally made a decision on what to do with the rest of my life. I decided to write.”

It’s a decision that he’s still living with after nearly 30 years of writing poems and, he said, one novel. He is an unpublished poet, to be sure. But so was Emily Dickinson in her lifetime, when, according to her biographers, she wrote more than 2,000 poems--of which only 20 or so were published before she died in 1886.

Not that Ronnie Knox will be the next Emily Dickinson, but he has written hundreds if not thousands of poems, and he has read thousands of others if not millions. He talks about poetry and his other literary interests nearly all the time--as he has for about three decades.

A visitor changes the subject once more, getting back to his early departure from football, whereupon Ronnie quotes English poet A.E. Housman:

Twice a week the winter through

Here stood I to keep the goal.

Football then was fighting sorrow

For the young man’s soul.

He said it’s a stanza from, “To an Athlete Dying Young.”

Next, a visitor’s chance remark reminds Knox of the night that the philosopher Aristotle, sitting quietly under a full moon on an Aegean beach, mused aloud, “How come the moon doesn’t fall on us?”

“Good question,” Knox said. From the hindsight of his own century, he added, “It is.”

Knox hasn’t, however, entirely forsaken his mundane old hobby. He volunteered, for example, that the nation’s standout modern coach is Bill Walsh. And as a student of football strategy, Knox still enjoys coaching the game, he said, now and then.

Dr. Roland Rasmussen of Canoga Park’s Faith Baptist Church and Schools has been his most faithful employer, bringing him in three times--in ‘72, ’77 and again this summer--to coach his eight-man football teams.

Knox never stays long--he learned a different way in high school--but as a football man, he has made a strong impression on Rasmussen, a pastor who discusses football with the efficiency of an expert.

“We got acquainted through his mother when she was a member (of Faith Baptist) in 1970,” Rasmussen said. “Ronnie relates beautifully to athletes--he gets the most out of each one--and he has a brilliant football mind. I think he could be an offensive coordinator anywhere.”

In fact, the pastor said, Ronnie could have been making a living as a National Football League player as recently as 1977, at least as a punter. That year, when Ronnie was 42, he and another Faith Baptist coach often played catch--Ronnie punting, the other guy catching.

“(The other coach) would run a deep pattern to the sideline,” Rasmussen said. “And Ronnie would punt it (to him) 50, 60 yards away. He hit him perfectly every time.”

Still, Knox would rather write poetry. The great tragedy of his life, he said, was losing all of his poems--along with the 400-page manuscript of his only novel--when his luggage was stolen about 10 years ago in front of a motel in Galveston, Tex. He was then at a maritime school preparing for still another career that never quite materialized.

Although Knox has since built up a respectable inventory of new poems, the thief robbed the world of what he called his masterpiece, “Masquerade,” which dealt with the theme that has dominated his days and nights for nearly a half century: Is all this a dream, or is this the reality?

He holds that in any case, what seems to be reality can always be blind-sided by a dream.

Using art and dream almost as synonyms, he also uses reality and history interchangeably, and then concludes--along with Aristotle, he said--that art is superior to history.

“Art can be controlled,” he said. “Reality is arbitrary and uncontrollable.”

And often, he might have added, uncomfortable.

HARVEY THEN

The Knox entry reached its summit one January day in Pasadena in the only big football game the family ever reached, the 1956 Rose Bowl game, in which Michigan State beat UCLA, 17-14.

Ronnie had broken a leg carrying the ball against Washington five weeks earlier, so UCLA’s Sanders, a single-wing hard-liner, didn’t want to use him in the Rose Bowl. Although the player had healed swiftly, regaining 100% form as a passer, the coach feared that a recently injured tailback wouldn’t add much to Sanders’ cherished ground game.

When Ronnie eventually appeared in the fourth quarter, UCLA had only scored after an intercepted pass and Michigan State was ahead, 14-7. Throwing with his usual aptitude, Ronnie moved the offense impressively, mounting a long touchdown drive, after which the Bruins ran out of time.

The easy but skillfully earned touchdown both pleased and angered his stepfather, who was writing a first-person account for the old Los Angeles Examiner.

The gist of the Knox family evaluation was in the big Page 1 headline: “SANDERS BLEW IT--Harvey.”

Every sports fan in town could identify the source. For years, Harvey Knox had been as famous as his ballplaying stepson. It was generally understood in Los Angeles that Ronnie was no more than a puppet and that Harvey was the captain of the team.

When, for instance, Ronnie left Berkeley on his way to a new home at UCLA, a typical newspaper headline told the story: “Harvey Pulls Ronnie Out of Cal.”

It was a good story, but inaccurate. Harvey was such good copy--he was forever telling off Ronnie’s coaches--that the truth wasn’t at all clear 30 years ago.

The truth was that Ronnie, the bright and strong-minded son of an atom-smashing physicist, made the big decisions himself, pulling the strings quietly. The stepfather, a born ham, merely implemented them while joyously taking credit.

“You wanna make money, you gotta get ink,” Harvey said here recently--not for the first time.

Even as a 15-year-old high school sophomore, Ronnie had personally made the fateful decision to start city hopping--the course he’s still on. When Harvey saw in 1950 that he couldn’t keep his boy in a losing program at Beverly Hills, he recommended nearby Santa Monica High School, where, in the view of knowledgeable football people, Jim Sutherland had proved to be the class of Southern California coaches.

Ronnie vetoed the suggestion. As the Knoxes remember it now, he told Harvey: “Sure, he’s the best coach, but I can beat him. Let’s move to Inglewood and do it.”

This turned out to be a humbling experience. “Ronnie found that one player--even a quarterback--can’t make that much difference in an 11-man game,” Harvey said. “Especially when the coaching is lousy. We’d had two lousy coaches in two years, and why keep batting your head against a wall? As a senior, we joined Sutherland.”

Thus, at long last, Harvey got his way.

He had come from nowhere to become the spokesman for a 1950s prodigy.

Son of a railroad man who fell off a train one night and left four children, Harvey progressed from an orphanage in Monticello, Ark., to the University of Arkansas, where he played a little football as a 168-pound end.

He made his first bundle selling encyclopedias, lost it trying to expand, and in the 1930s took a train to California.

“I sat up 11 days and 11 nights,” he recalled. “It was a freight train.”

In the West, after making and losing other fortunes in dry ice, Las Vegas hotels, and a detective agency, Harvey was left, he said, with nothing but three Jaguars, which were custom painted in three colors to match the eyes of three girlfriends.

Vowing to recoup, he moved to 268 North Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, where he established himself as a men’s haberdasher and custom tailor.

An early customer was film star Ginger Rogers, who walked in one day and ordered a dozen pair of custom-made pants.

“It was her idea, but we began calling them women’s slacks,” Harvey said. “We built and sold the world’s first women’s slacks.”

A more conventional customer was Howard Hughes, who was to build, among other things, the world’s first Spruce Goose. So when Harvey had made and, at the outset of World War II, lost another fortune, he patriotically hit up Hughes for a job at an aircraft factory.

There he spotted, as she made machine guns one day, “the most beautiful girl I’ve ever seen.”

A courtly, old-fashioned type when he chooses to be, Harvey got “my friend Howard Hughes to introduce me to this charming, patriotic lady,” whose name, he had learned, was Marjorie Landry. She was the mother of a 9-year-old daughter, Patricia, and a 7-year-old son, Ronnie.

Harvey and Marjorie were to experience a Hollywood romance: They were married the day that she divorced Professor Landry.

On their first Sunday together, Harvey began reliving his life through a child, taking little Ronnie out to Beverly Hills’ Roxbury Park.

“We’re going to play football,” Harvey told him.

Foreshadowing his future, Ronnie said, “I don’t want to,” and began to cry.

Then, as Harvey tells it, a strange thing happened. He walked away from Ronnie, 35 or 40 yards away, then turned and suddenly threw the ball directly at him.

As the 7-year-old boy straightened up and went for the first football he’d ever tried to catch, he caught it firmly with the practiced grace of a pro receiver.

“He was a natural,” Harvey said.

A reluctant natural.

HARVEY NOW

On a recent Sunday afternoon, Harvey was standing on a McKinleyville rise--a short lateral pass from the water--when a Los Angeles reporter ran into him for the first time in 33 years.

Harvey and his partners own the wooded rise.

Surrounded by the stone castles he has built at his elaborate residential project on Knox Cove, he was wearing old work pants, old work shoes and an old red jacket that couldn’t conceal the paunch he never had when he was a man about Hollywood. The clean white hair and mustache contrasted vividly with the red jacket. He said he’d be 80 the next time around.

He went to dinner that night without so much as changing his shoes at the guest house where he has been living on one of the cove’s stone-castle estates. At Merryman’s Restaurant, he was given the best corner table overlooking a rocky shore of the Pacific, and he put a visitor in the chair that had the best view of the red sunset.

The Merryman guests and waitresses all seemed to know him well. “We’ve missed you,” said a guest in a black and white dinner dress. “Where you been, Harvey?”

Looking her in the eye, he said: “I’ve been broke.”

Later, he confided that a month ago, he was $75,000 in debt. He had gone through another fortune. “Any time you think you’ve got it made,” he lamented, “it begins to slip away.”

As another party of dinner guests drifted in, greeted Harvey warmly, and sat down in a dozen seats at a nearby table, Harvey whispered: “See that guy in the middle? Best businessman up here. Laid $80,000 on me last month.”

Bought one of Harvey’s lots, that is. And threw in a down payment on a house. Overnight, Harvey could pay all his bills and make his first run at a new fortune.

Down the road, he said, he wants to share this one with his children. His stepdaughter, Patricia, a millionaire who lives in Florida and plays tennis five days a week, flies in to see him once or twice a year. Ronnie comes up occasionally, as does Montgomery, 33, a Malibu nurseryman, the only child of Harvey and Marjorie.

Marjorie is 75. “My beautiful wife, my darling Marjorie, is dying (of a brain tumor),” Harvey said.

In California many years ago, Harvey had taken a fatherly interest in both of Marjorie’s children. For one thing, he helped Patricia land her first movie contract. She was then 15, and playing the lead in a Beverly Hills High play, but attracting no attention.

So Harvey hired a guard to stand at the door with a big sign reading: “No talent scouts admitted.”

At the next performance, “Three of the bums (talent scouts) were camping on the front row,” Harvey said. “And Patricia took the best offer.”

Harvey remembers that day exultantly. But it was no more than he ever did for Ronnie--whenever, that is, Ronnie could make up his mind to take an offer.

The Pigeon on the Steeple By Ronnie Knox

1 Before me was the church, A Christian church in a country town. The roof was broken all about; and a green door Beaten bad to brown.

2 (In a soft sun I knew-- Deeper than all energy-- That miracles go home to miracles, As silence moves to silence, without a whisper.)

3 The tower’s faithful bells, accepting the coin Of myriad surrenders to the whip and chain Of damp nights, now languished In rust greater with each rain.

4 “Good afternoon, sir,” I said. “Likewise, I’m sure,” said the passer-by. “How old’s this church, you know?” “Hard to tell,” he replied. “Leaves are for a season, “But the tree?--Hard to tell,” And he winked his eye.

5

A solitary pigeon, part of history as I, Fluttered down upon the steeple. Pride rippled in the rainbow round her neck: Azure, mauve, gray, patina green, white and purple.

6

No more souls, I knew, Would pass beyond this latticed gate. No more eyes would lift their reach to God. No more silent wrenching cries would challenge fate.

7

“Be not deceived,” became the warning, “By the phantom’s lively dance; “Earthly doubts are cunning-- “Reflections not of chance.”

8

As I mused thus, the sky turned dark, And upon my town rain did fall. I turned--and walked away--but then Turned back as if on call.

9

And there upon the steeple yet, The rainbowed pigeon sat Waiting for another soul. And I wondered: Did love come before or after that?

Times researcher Doug Conner contributed to this story.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.