What to see in L.A. galleries: An ode to a black sci-fi trailblazer and Lari Pittman ‘Mood Books’

The best part of “Radio Imagination: Artists in the Archive of Octavia E. Butler” is the view it provides into Butler’s archive itself. Butler, who died in 2006, was a bestselling Pasadena novelist and the only science fiction writer to win a MacArthur fellowship. She was also African American, and her novels reworked the sci-fi genre with far-reaching insights on race, sex and gender.

The exhibition at the Armory Center for the Arts in Pasadena features works by eight artists who were granted access to Butler’s archives at the Huntington Library in San Marino. Their responses take a variety of forms, including sound and video as well as photography, drawing and installation. But the most engaging “work” is a slideshow of selections from Butler’s papers. It spans her lifetime, from childhood writings and drawings to rejection letters, photographs, and most strikingly, cards and pages of notes. These are remarkable for the affirmations Butler wrote day after day, reminding herself that she would be successful — famous novelist, a bestseller — and that she had no one to rely upon but herself. They are documents of determination.

This drive is embodied poetically in the audio piece “Ring Shout (for Octavia Butler)” by Mendi + Keith Obadike. It blends text from an unpublished story Butler wrote as a teenager with an African American folk song and electromagnetic sounds from the Earth’s atmosphere. It narrates how a young girl is given the name Star, although she doesn’t yet know what the word means. Paralleling Butler’s rise from obscurity, the piece will eventually be launched on a satellite to be broadcast from space.

Back on Earth, photographer Connie Samaras superimposes images from Butler’s archive onto beautiful shots of plants from the Huntington Botanical Gardens. The images are lush and somewhat romantic: Butler’s figure appears ghost-like among the roses while snippets of her writing wind their way through the leaves. They bring Butler’s own past and her future imaginings to present-day, exuberant life.

Similarly, Lauren Halsey’s room-filling installation is a chunk of icy landscape derived from a description Butler jotted down. In its sheer size and detail, it becomes a sculptural analog to the writer’s ability to realize imagined worlds.

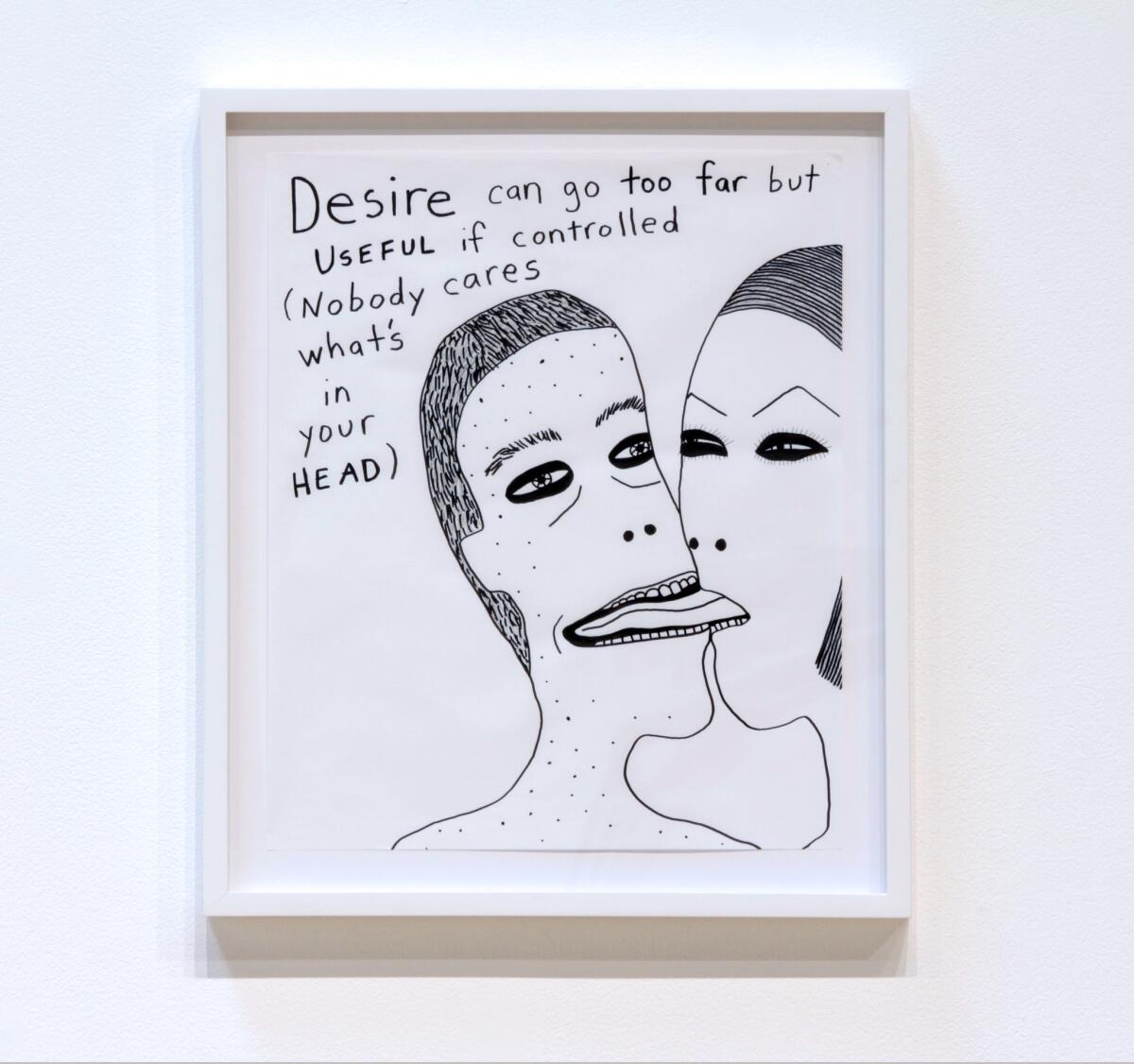

Laylah Ali’s black-and-white drawings illustrate quotes from Butler’s diaries dealing with female desire and sexuality. Reminiscent of the work of Dorothy Iannone, they have a freakishly powerful appeal, both personal and alien.

Malik Gaines and Alexandro Segade’s contribution is an animated video, rendered in rainbow colors and primitive graphics, set to the words from an unfinished Butler novel. A choral piece, performed on the show’s opening night, is represented by a printed score. These works are intriguing, but it’s obvious they are only artifacts of the main event.

And finally, in the backroom is Cauleen Smith’s video based on Butler’s breakout book, “Kindred.” Or rather, the video is a censored version of the piece Smith originally created. Because Smith does not own the film rights to the book, Butler’s estate requested that she remove her original video from the exhibition. In response, Smith added a personal preamble and redacted parts of the video with bleeps and black boxes.

In the preamble, Smith compares the ownership of bodies (“Kindred” deals with time travel and slavery) and the ownership of ideas as twin evils of capitalism. Just as the novel’s protagonist returns from her travels with an amputated arm, Smith’s piece is similarly maimed. Yet the redacted video is actually a more fitting tribute, weighing as it does the freedom of imagination against the dangers of inhabiting a black body in America.

Armory Center for the Arts, 145 N. Raymond Ave., Pasadena. Through Jan. 8; closed Mondays. (626) 792-5101, www.armoryarts.org

Elana Mann has achieved a rare kind of poetry with her “Assonant Armory” at Commonwealth & Council. The exhibition consists of an array of custom-made megaphones, fashioned from life-casts of arms raised in the “hands up” position.

These surreal creations are also functional: The user speaks into a small hole in the palm of the hand, and the sound comes out amplified by a trumpet-like shape at the other end. The “hands up, don’t shoot” gesture, already transformed from an expression of submission into a protest against police brutality, here gets another life as a vehicle for broadcasting speech.

The works also transform a gesture associated with silencing — putting a hand over one’s mouth — into an act of amplification. In a clever alchemy, these acts of capitulation are recast as a means of greater expression.

The megaphones rest on custom pedestals or hang from straps on the wall, as if ready to be worn in the field. A few are inserted through the walls so that a speaker on one side can be heard on the other. I’m sorry to have missed the opening night performance in which a group of artist-activists used them to broadcast sounds from the electoral season.

Speaking of which, there is one piece that does not look like an arm. “Donald Trump(et)” is a traditional, cone-shaped megaphone whose golden mouthpiece is made from a life cast of a body part found at the very end of the digestive tract. Unlike the rest of the armory, it does not work.

Commonwealth & Council, 3006 W. 7th St., Los Angeles. Through Nov. 5; closed Sundays and Mondays. (213) 703-9077, www.commonwealthandcouncil.com

Lari Pittman’s “Mood Books,” on view at the Huntington’s museum, are giant follies. Six extra-large books, each more than 4 feet wide when opened, contain Pittman’s highly detailed, cacophonous paintings, mounted in thick beige mats.

The works address various themes with a story time bent: happenings under a full moon, apparitions, newly discovered constellations. Like much of Pittman’s work, they limn the weird and wonderful within an aesthetic of graphic overload.

The books give Pittman’s whimsical imaginings the heft and grandeur of scripture or legend. If you are a Pittman fan, this will likely be a good thing. For me, the paintings aren’t transporting enough to escape their ponderous setting, instead giving off a strong whiff of self-indulgence.

This impression is furthered by the fancy exhibition design by architect Michael Maltzan. His long custom pedestal nests all six books in cradles that curl upward into Gaudi-esque points, isolating each book from the next. Only one spread of each is on view at any given time, and viewers are not allowed to turn the pages. Maltzan has added curving guardrails to ward us off.

A touch-screen interface allows all pages of all six books to be viewed. (It is also available online.) This is a far better way to see the paintings, allowing their serial nature to emerge but also questioning why the books were made in the first place.

Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, 1151 Oxford Road, San Marino. Through Feb. 20; closed Tuesdays. (626) 405-2100, www.huntington.org

I can’t decide whether Thomas Hirschhorn’s installation “Stand-alone” is brutal or brutalizing. Probably both.

Created in 2007 and making its U.S. debut, the work fills four galleries at the Mistake Room with an overabundance of upholstered furniture wrapped in packing tape and oversized fireplaces stuffed with giant logs, their mantels groaning under the weight of philosophical tomes. There are piles of enormous green pills, each one engraved with the word “you,” and dilapidated bookcases filled with printouts of redacted news articles.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

The walls are studded with dead television and computer monitors and are covered in clichés and sound bites written in a crude graffiti style; there are weirdly spongy spots in the linoleum floor. But the coup de grâce in each room is a huge fake log that appears to have crashed through the space. Each one is studded with grisly photographs of severed limbs and bloody, maimed bodies. No punches pulled.

The work was conceived as an exploration of the Swiss artist’s creative process in relation to social issues and philosophy. In light of current events, it feels more like a collective nightmare, a surfeit of unnamed violence and vileness coursing through our mummified living rooms over and over again. The experience is so unrelenting in its horribleness it nearly brought me to tears. That’s a triumph of sorts, but also a trauma.

The Mistake Room, 1811 E. 20th St., Los Angeles. Through Dec. 17; closed Sundays through Tuesdays. (213) 749-1200, www.tmr.la

Follow The Times’ arts team @culturemonster.

ALSO

What to see in L.A. galleries: John Altoon, Maria Lassnig, a funky fairy tale and stenciled magic

Polly Apfelbaum's fallen paintings and beads of devotion in her secular chapel of abstract art

Step inside a digital storm: Andy Warhol's 'Rain Machine' brought back to life after 45 years

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.