4 ways Brazil has changed since former President Dilma Rousseff was impeached

Barely a month has passed since Brazil’s Senate voted overwhelmingly to remove President Dilma Rousseff, putting an end to both 13 years of Workers’ Party rule and a controversial impeachment process that seemed to drag on and on.

Since then, Latin America’s largest country has seen some major and minor shifts. Here are four things to know about the world’s fifth most-populous country.

Fractured international relations

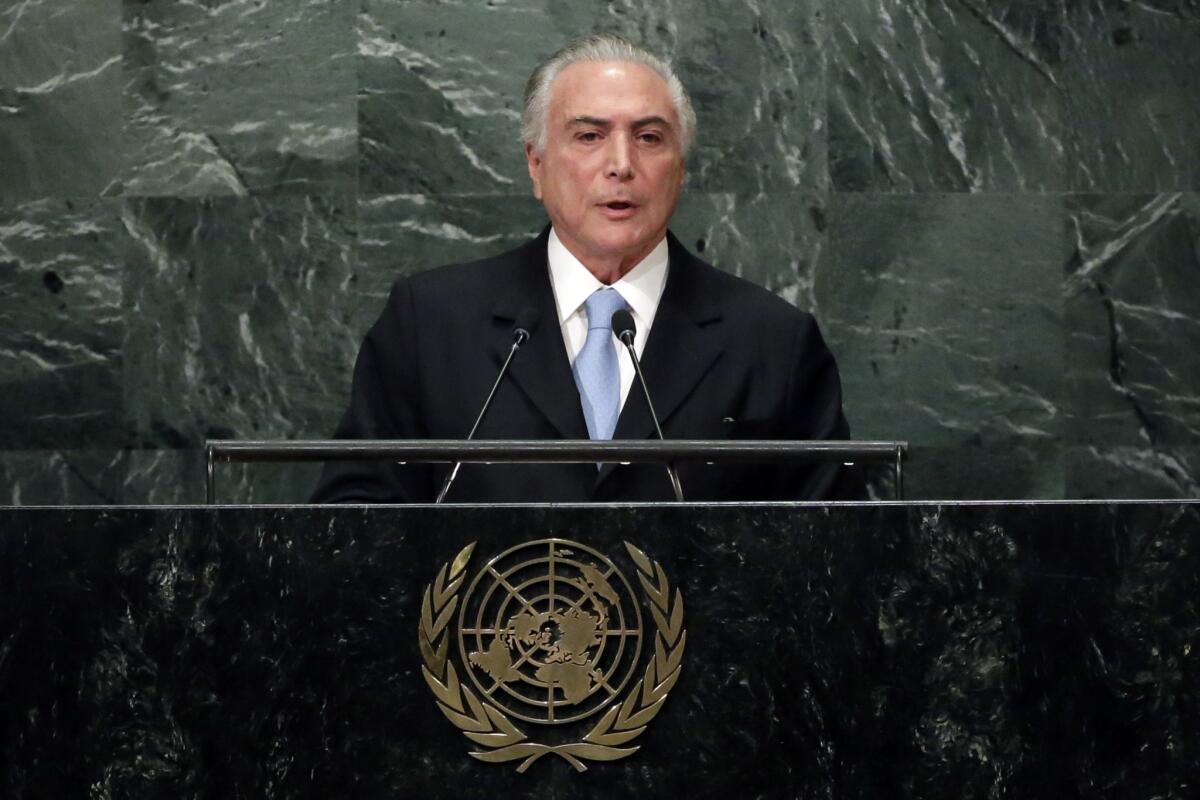

The new government of Michel Temer, the vice president under Rousseff, quickly found that impeachment has led to new diplomatic divisions in Latin America, most forcefully underlined by a dramatic scene at the U.N. General Assembly.

Brazil is traditionally a neutral international power, and for much of the 21st century maintained good relations with the Latin American countries moving to the left, as well as its more conservative neighbors and the U.S.

But as Temer took the microphone to speak in New York in September, representatives from Bolivia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador and Nicaragua walked out of the hall, saying they would not listen to an illegitimate leader.

“There is no precedent for something like this in Brazilian history,” said Mauricio Santoro, a political scientist at Rio de Janeiro State University. “There are major shared economic interests and real benefits for Latin America to remain united, and I didn’t think we’d see that level of diplomatic conflict.”

Some international observers have welcomed new Foreign Minister Jose Serra’s willingness to criticize Venezuela after Rousseff’s silence about economic problems largely blamed on the leftist government. But there is more at work behind the new split. Some governments believe that Brazil’s impeachment sets a dangerous precedent for removing any president whenever other politicians and power brokers choose.

Prosecuting Lula

For years, extremely popular former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva has been the most potent political force in Brazil. And since 2014, the corruption probe code-named Car Wash has achieved remarkable success in prosecuting political and business figures, earning broad support from the Brazilian population.

But in September, Lula and Car Wash crashed into each other in a strange spectacle that put both of their fates in jeopardy.

A judge ruled that Lula can be tried on charges of money laundering and corruption. But while presenting allegations that Lula received approximately $1 million in benefits from a construction company, prosecutor Deltan Dallagnol also made a series of broad accusations— without presenting any evidence — that Lula was the mastermind of the entire corruption scheme surrounding the state-run Petrobras oil company, the main scandal uncovered by Car Wash.

Dallagnol’s presentation was criticized even by Lula’s opponents, and his supporters saw a politically motivated attempt to neutralize Lula as a political force. Especially bizarre was a PowerPoint graphic that strained logic by simply showing a large number of arrows pointing at the name “Lula,” and the image went viral on Brazilian social networks.

“Dallagnol made an enormous mistake,” said Brian Winter, vice president for policy at Americas Society and Council of the Americas. “It might eventually be forgotten if there are other big arrests or revelations. But it certainly reinforced the perception that the probe has become too politicized, and will increase pressure for investigators to conclude their work in coming months.”

Punishing recession

Brazil remains mired in the worst recession in a century, and 2016 will remain a difficult year. But even though Brazilian citizens have repeatedly told pollsters they would prefer new elections as a means of picking a president to finish the remainder of Rousseff’s term, many international investors and local business elites have long been united behind the “Temer solution” to avoid short-term volatility and get the economy back on track.

Polling shows that Temer is not a popular president, and it’s very likely he won’t be when his term ends in 2018, said Joao Augusto de Castro Neves, Latin America director at the Eurasia Group, a risk-analysis organization, in Washington. But at the very least, he said, Brazil may have seen the end of political gridlock.

“Temer just wants to deliver a country slightly better off than when he started,” he said. “And now there is the perception that next year may be better than this year.”

Same divisions, different protesters

The tumultuous last few years of Brazil’s political and economic crisis have led to an increasingly divided population. Conflicts remain, but the various sides have switched positions.

From the beginning of Rousseff’s second term in 2015 until her suspension in May, protesters periodically demanded her removal. They wore Brazil’s national colors of yellow and green, were broadly conservative and tended to get on exceedingly well with police.

Now, the demonstrators demanding the fall of the government tend to come from Brazil’s traditional left. They often wear red and their slogan — heard often during the Rio 2016 Games — is “Fora Temer,” or “Out With Temer.” Their protests, usually smaller than the anti-Rousseff demonstrations, tend to end in clashes with military police, a traditional enemy of progressives here since the dictatorship, which ended in the 1980s.

But Brazil’s political configurations are much more complex than the U.S. two-party system. There are more than 30 active parties here, and allegiances shift constantly.

In Sunday’s municipal elections, voters punished Rousseff’s Workers’ Party around the country, while some of Temer’s major allies also struggled, and the country saw record levels of voter abstention. Many of the mayoral races will be decided in a second round in late October.

At the federal level, many of Temer’s new supporters in Brazil’s Congress — where a majority of members themselves face more serious accusations of corruption or serious crimes than Rousseff ever did — were actually part of Rousseff’s coalition. Overall, however, the government has ditched its left wing and will probably see continued attacks from this direction.

Bevins is a special correspondent.

ALSO

Polish women protest proposal to ban abortions in almost all cases

Britain’s exit from European Union expected by summer 2019

Battle for Mosul could spark ‘one of the largest man-made disasters’ in years, U.N. warns

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.