Young rappers are getting honest about doing battle with depression, drug addiction and suicide

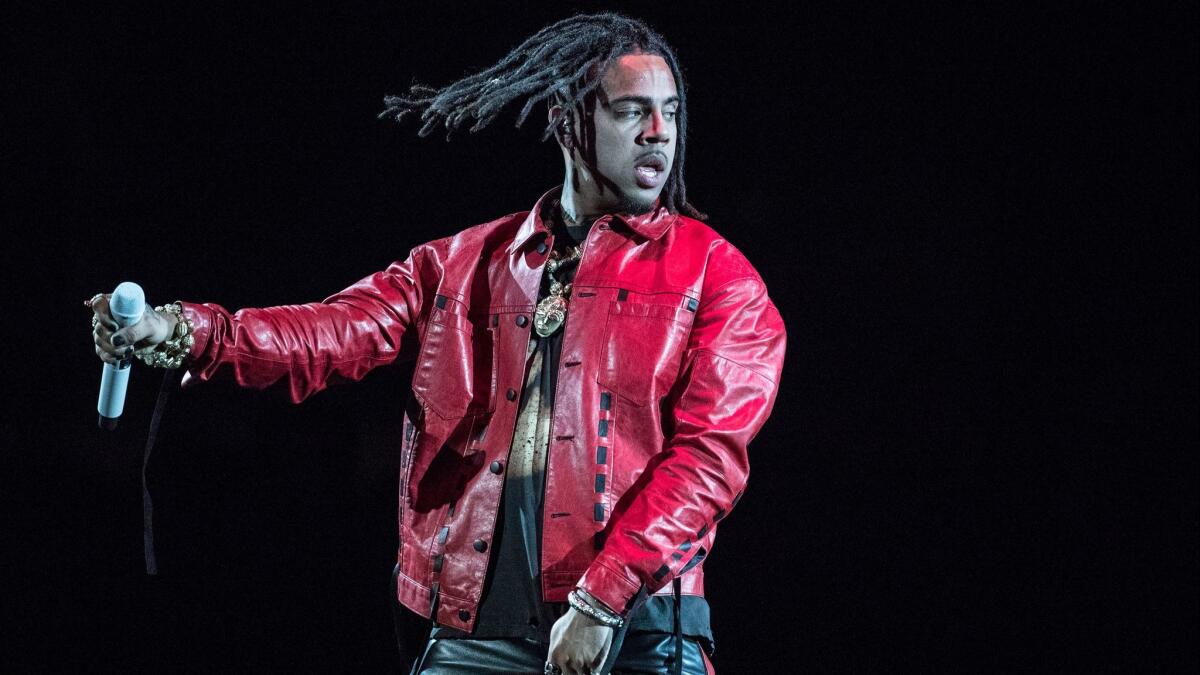

Back in December, in front of a sold-out audience at the Forum awaiting Grammy front-runner Jay-Z, opening act and rapper Vic Mensa vaulted onstage. Dressed in punky red leather, he was boisterous and triumphant, the show a crowning achievement in his career.

But underneath the bravado were lacerating lyrics about depression and drug addiction.

“In the cyclone of my own addiction,” he rapped on his song “Wings.”

“The voices in my head keep talking… / ‘You’ll never be good enough…you never was / …You hurt everyone around you, you’re impossible to love / …I wish you were never born, we would all be better for it / …You’re still a drug addict, you’re nothing without your medicine / Go and run to your sedative, you can’t run forever, Vic.’”

Hip-hop artists Jay-Z, Kendrick Lamar and Logic will likely dominate the top Grammy categories, doing so in a year the genre went deep into issues of mental health, drug addiction and suicide — topics that have long been present below the surface. Some acts, such as Logic (with Khalid and Alessia Cara) will tackle those issues head on at the Grammy ceremony, where they’ll perform the smash “1-800-273-8255” (which directs fans to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline) with a group of suicide loss survivors and people who have recovered from suicide attempts.

Rapper Logic speaks on the benefit of being positive. Read the interview here.

After the song’s music video went viral, calls to the lifeline went up between 30% and 50%, said John Draper, the suicide prevention line’s director. “That’s thousands of callers who otherwise wouldn’t have called,” he said. “Messages like Logic’s, where he says, ‘I’m thinking about suicide, but I want to get help’ and he got it, are a a very positive model.”

But some, like the promising rapper Lil Peep, didn’t hear it in time. Peep died at age 21 in November of a suspected overdose, after a short career where he wrote openly about his suicidal impulses and drug addiction. Many of his young peers in the “Soundcloud Rap” generation lyrically fetishize abusing prescription drugs like Xanax or “lean” (a codeine-laced cough syrup drink), with some such as new artist nominee Lil Uzi Vert alluding to suicide, violence or overdosing as a likely fate for most everyone they know.

Now that the genre is finally more open about its dark mental storms, how should artists write and work in honest ways, while also helping those who are truly suffering?

Young black men experience a lot of trauma. They’ve lost people, seen violence, been humiliated by society.

— Vic Mensa

“It was big for me to recognize that drugs are a symptom of an underlying issue,” Mensa told The Times after the show. “You see it in hip-hop; you see it in punk. These kids come from nothing. Young black men experience a lot of trauma. They’ve lost people, seen violence, been humiliated by society. So they turn to alcohol, molly, lean.”

Songs like Logic’s might be one way to help that message reach young people and music fans who see a stigma around mental health treatment. “1-800-273-8255” was an unlikely pop sensation — it hit No. 3 on the Billboard Hot 100 and made “Everybody” his first No. 1 album.

It’s nominated for song of the year, even though its hook seems bleak at first — “I don’t wanna be alive / I just wanna die today.”

SPECIAL SERIES: The Age of Hip Hop -- from the streets to cultural dominance »

But then the verses do an astonishing thing. Logic (whose reps said was unavailable to speak for this piece) confronts those feelings, acknowledges and analyzes them and finally realizes that he does, in fact, have the power to seek help and move past them.

“You gotta live right now / You got everything to give right now,” he raps. Then the chorus changes: “I finally wanna be alive / I don’t wanna die today.”

For Draper, it’s a perfect model of how an artist should write about suicidal thoughts. “There’s a difference between suicide awareness and suicide prevention. It’s very easy to glamorize it and get the message wrong,” he said. “Art can connect people with suffering, but there has to be hope on the other side. It doesn’t have to end in tragedy if you give people an action step.”

Mensa’s “The Autobiography” was a landmark in this conversation last year. The album is unsparing about his own descent into addiction but wise and empathetic about the causes of dependency (among them, the violence, isolation and hopelessness in poor minority communities) and the possibility of redemption.

I’ll be in the studio and see three of them sitting there and it’s like ‘It’s 9 p.m. on a Tuesday; why are you doing coke?’

— Vic Mensa

Mensa takes pains not to judge anyone’s trauma and addictions, but he admits that addiction and mental illness are currently endemic in hip-hop (and in music generally).

“A lot of my friends are addicted to drugs, and we just don’t talk about it,” he said. “I certainly can’t speak from any holier-than-thou perspective. But I’ll be in the studio and see three of them sitting there and it’s like ‘It’s 9 p.m. on a Tuesday; why are you doing coke?’”

Mensa’s two years of ongoing sobriety have given him a new perspective that led to the most important music of his career. “All the feelings I’d been repressing and escaping came out in music, and that was very cathartic and necessary for me,” he said of “Autobiography.”

What finally got him out of addiction was finding accessible communities (such as 12-step programs), tools (the right mix of medicines) and pathways to recovery such as professional therapy: all things he wished he’d known about when he was much younger.

“It begins on a community level. Therapists should be available for grade school kids in the hood,” he said. “We barely had a nurse there once a week.”

But so much difficult work still remains to be done. It can be hard for fans, peers and loved ones to know quite what to do with an artist like Lil Peep, whose death last year from a suspected Xanax-linked overdose upended the hip-hop and punk scenes alike.

On the one hand, his lyrics had the nihilistic glamour that Draper warned of: “Cocaine lined up, secrets that I’m hiding / …You don’t wanna cry now, better off dying,” he rapped on “Better Off Dying.” “Even if I try hard, I ain’t gonna make it.”

‘Live fast, die young’ is just about the oldest sentiment in pop music. Everyone from pre-war blues acts to Kurt Cobain has toyed with the theme.

But that sentiment was part of his illicit allure to young people, and millions of fans identified with it in some way or another. “Live fast, die young” is just about the oldest sentiment in pop music, and everyone from pre-war blues acts to Kurt Cobain has toyed with self-destruction as a theme.

When an artist like Lil Uzi Vert raps something like “Might blow my brain out / Xanny [Xanax] numb the pain yeah / Please, Xanny make it go away,” it’s tough to delineate an edgy performer playing a dark character from a person who might be alluding that they need help. The same goes for fans, some of whom just like the delicious bleakness of a song like his “XO Tour Llif3” or Future’s “Mask Off.” But some others with mental illness may feel the pull of a truly harmful idea.

“Some music can glamorize addiction and substance abuse. There’s a difference between speaking out about your troubles and glamorizing that lifestyle,” said Adam Leventhal, the director of USC’s Health, Emotion & Addiction Laboratory.

“There’s a belief in some communities that you’re just supposed to be strong and handle your business and not talk about it or that it’s somehow your fault. These ideas have been perpetuated for generations, in part by media and through social circles.”

Young people face some distinct challenges in the ongoing national crisis with drugs (especially opioids) and depression, Leventhal said. Many lack the resources to pursue professional counseling or face pressure and abuse at home.

But if culture can be a stigmatizing influence on mental health, it can also be a way out.

Leventhal wasn’t yet familiar with “1-800-273-8255” when he spoke with The Times, but upon hearing that it was a Grammy front-runner and a smash hit single, he grew heartened that such a message was resonating with young people.

“If peers and friends are talking about their own experiences with substance abuse or mental illness, as a society we’re highly influenced by them and by people who hold high places in our culture. Logic is a great example of how to own your own struggles and destigmatize them,” he said.

“There are so many ways for people who are suffering to seek treatment,” he added. “Any way to remove the stigma helps, and that can include popular culture and artists who resonate across their communities. That song could be a game changer.”

The Age of Hip-Hop

From the streets to cultural dominance

The 2018 Grammy nominations are overdue acknowledgment that hip-hop has shaped music and culture worldwide for decades. In this ongoing series, we track its rise and future.

ALSO

Peace, love and Logic — meet the rapper who’s taking on the world with positivity

Rolling Loud’s SoCal debut underscore’s hip-hop’s cultural dominance

Why hip-hop, once ostracized in clubs, is ruling the festival circuit

The moment N.W.A changed the music world

For breaking music news, follow @augustbrown on Twitter.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.