Taylor Swift, Mary J. Blige upend music world with creative disruption

No less than the taxi industry or the news media, the music business was defined in 2014 by disruption: that tech-world buzz word referring to the way a given field is upset — and in some cases remade — by new players armed with new strategies.

Think of Beyoncé releasing her self-titled album one evening last December with no warning, a hugely successful digital-era stunt that made her peers question the value of the traditional promotional campaign, much as Uber has forced cab companies to rethink how they acquire passengers. In recent weeks, rapper Azealia Banks and soul singer D’Angelo followed Beyoncé’s lead by suddenly unleashing long-labored-over albums that many fans had feared would never appear.

Yet if musicians and record labels faced increasing pressure to adapt their delivery methods this year — all in an effort to avoid having an album release feel, as Billy Corgan of Smashing Pumpkins fame put it, like “a cultural yawn” — that demand for innovation was nearly matched by a kind of creative self-disruption.

Throughout 2014, acts from across the pop-music spectrum, from Mary J. Blige to Taylor Swift, shook up their processes in conscious attempts to stay in the conversation. Headlines were made, though artistic results varied.

The most fruitful of these projects came from Blige, the veteran R&B star whose album “The London Sessions” revived a career that seemed to be sliding into irrelevance with releases like last year’s ho-hum “A Mary Christmas” and a set of songs, issued to remarkably little notice, tied to the Kevin Hart comedy “Think Like a Man Too.”

“I was starting to feel so stagnant,” she told Tavis Smiley on his TV talk show, so Blige went to London “to do what I needed to do and express myself as an artist.”

That meant hooking up with young British hit makers such as Sam Smith, Emeli Sandé and the dance duo Disclosure — all avowed Blige fans — to write and record a disc that recontextualizes her still-powerful singing. It trades the plush but slow-moving arrangements of her recent work for nimbler, more lightweight sounds, such as the shimmering synths in “Long Hard Look” and the skipping two-step beat in “Pick Me Up.”

As current as the record feels, though, the real success of “The London Sessions” is that its fresh settings allow Blige to convey the depth of her experience, as in the devastating “Whole Damn Year,” a plainspoken ballad in which she examines the damage done by a turbulent relationship and the length of time it will take her to heal.

An album that could’ve come off like a desperate bid for credibility instead reconnected Blige with the wisdom and spirit that made her sound like an old soul back when she was just starting out.

Sia pulled off something similar with her “1000 Forms of Fear,” using a manufactured sense of mystery to paradoxically boost the emotional impact of songs grounded in oddball specifics.

Known for her behind-the-scenes work as a songwriter on huge singles by Rihanna and David Guetta, among others, the Australian singer sought to preserve that not-quite-celebrity status — and to avoid what she’s described as the debilitating scrutiny of the entertainment press — by promoting “1000 Forms of Fear” without showing her face. The music video for her hit “Chandelier” starred an 11-year-old dancer; a performance on “Ellen” had Sia standing with her back to the audience.

A gimmick? Of course. Yet rather than de-personalize woozy, off-kilter songs like “Eye of the Needle” and “Big Girls Cry,” Sia’s disruption of pop’s cult of personality — a willing embrace of anonymity at a moment of ceaseless brand maintenance — actually made her music feel more vivid as you found yourself listening harder, searching for the signs of (real) life she declined to provide in interviews and photo shoots.

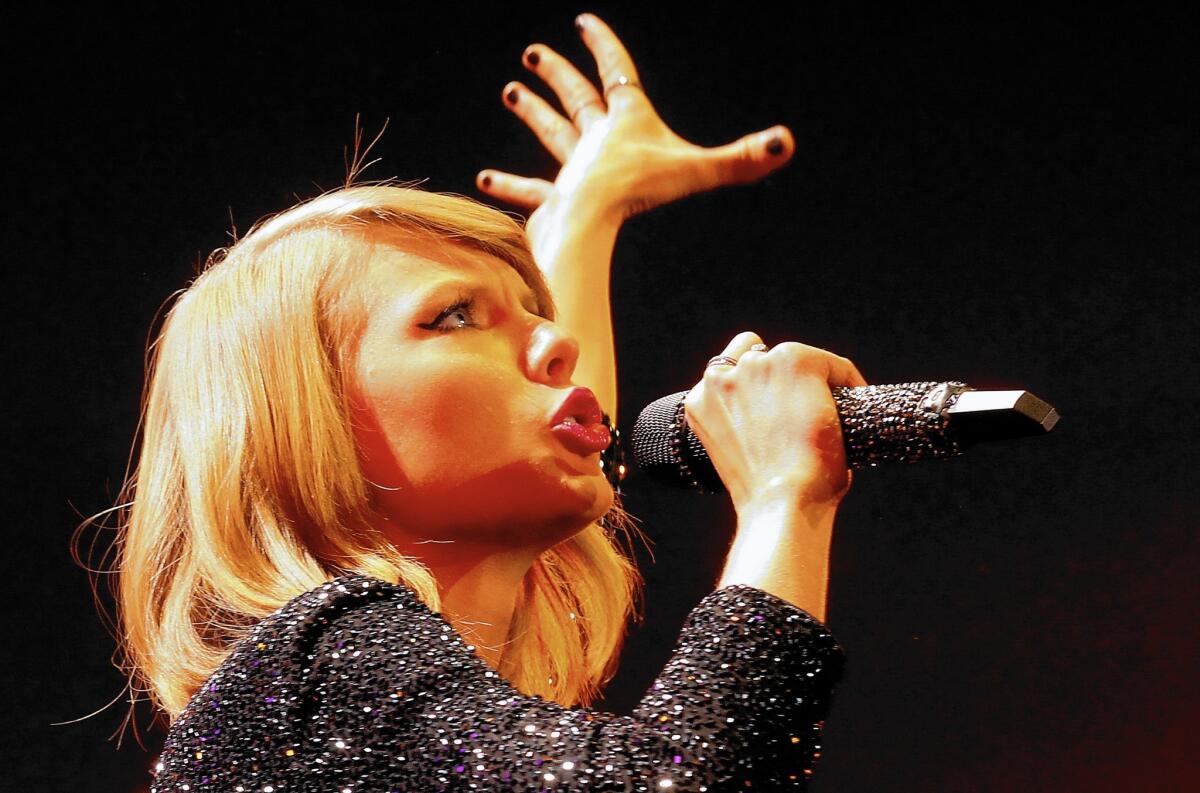

The opposite happened with Swift, who divulged plenty about herself, even hosting listening sessions for fans in her various homes, in the run-up to “1989,” the blockbuster album that she said officially finalizes her crossover from country to pop.

But with only a few exceptions, most notably “Blank Space” and “Style,” both of which toy with Swift’s reputation as a man-eater, the songs on “1989” lack the ultra-precise detailing that distinguished her earlier work, including the cuts from 2012’s “Red” in which she ventured just as boldly from country without first issuing a press release declaring her defection.

It’s as though she believed that switching camps, replacing banjos with dance beats, but also asking to be considered as part of a different peer group, meant she had to flatten out her lyrics too. And that’s a deep misunderstanding of pop by someone who grasped the form more tightly as a Nashville-based outsider.

Perhaps next time this vocal opponent of Spotify, the rising digital-music company, will be as brash in her music as she was this year in her business.

Dave Grohl was as open as Swift about his quest for new territory with the Foo Fighters. In the first episode of “Sonic Highways,” an HBO series about the making of the band’s latest album, the frontman talks about the problem of sustaining inspiration after 20 years of making records. His solution was to visit eight American cities known for their musical traditions and, with cameras in tow, write and record a song in each.

The idea is admirable, even honorable, in the way it unsettles our fantasy that aging artists never lose touch with the all-important muse. Like “1989,” though, “Sonic Highways” ended up far less exciting than its origin story promised; it’s the most generic rock record Foo Fighters have made, which suggests that the impulse to disrupt — a force we’re sure to see more of in 2015 — can propel an act only so far.

As with that chauffeured sedan you ordered up on your smartphone, the will to create still requires gas in the tank.

Twitter: @mikaelwood

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.