Scotland stands to win even if secession vote fails

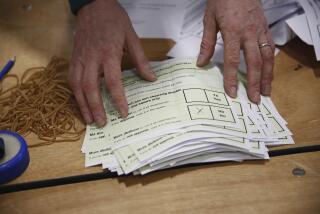

If the polls are right, supporters of independence for Scotland are heading for a disappointing defeat in next month’s historic referendum on seceding from Britain.

But in many ways, they’ve already won.

Even if Britain remains intact, Scotland appears set to wrest more powers from the central government in London. Britain’s main political parties, in a bid to persuade unhappy Scots to stay in the fold, have pledged to turn over more control of Scotland’s affairs to the semiautonomous Scottish government here in Edinburgh, especially on important tax issues.

Although that falls short of the cherished dreams of dyed-in-the-tartan nationalists, it would give this Celtic land a greater degree of self-rule than at any time since it merged with England and Wales in 1707 — and perhaps increase the hunger for more.

“They recognize the unstoppable move toward Scottish autonomy,” Ross Greer, a coordinator for the independence campaign, said of the parties’ promises. “All they’re doing is trying to slow it down as much as they can.”

Even if voters rebuff the chance to go it alone in the Sept. 18 binding referendum, Greer said, “we’ve won more powers for Scotland,” though many Scots, weaned on tales of centuries of English perfidy, are doubtful that politicians south of the border will keep their word.

With just a few weeks left before the vote, both the “Yes” and “No” campaigns are in full swing. Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond, who backs independence, and Alistair Darling, a former British finance minister and head of the Better Together campaign, this week held their second of two televised debates, with polls and pundits suggesting each won one of the matchups.

But before either man took to the podium for the first faceoff Aug. 5, the political debate in Scotland had already shifted dramatically as a result of the upcoming plebiscite.

Although the unionists still consistently lead in opinion polls, their advantage has eroded significantly enough in the last few months to send strategists scrambling to find new ways to woo voters, especially undecided ones.

That has wrought changes in both style and substance. Many Scots bristled at what they perceived as negative and bullying behavior from the pro-union camp, particularly the politicians in faraway London who threatened to snatch away the pound as Scotland’s currency in the event of independence and to revoke naval shipbuilding contracts in Scotland, which would, after all, become a foreign country.

Those dire warnings of “the day after” have now been scrapped in favor of emotional pleas to stick with the tried-and-true formula of Britain and the Union Jack, to try to counter the romantic appeal of a rugged, misty, emancipated Scotland standing proud on its own in the company of nations.

“It would break my heart to see our United Kingdom broken apart,” Prime Minister David Cameron said last month on a visit to Scotland. “Separation isn’t for a trial period. It would be permanent.” The diminished Britain would consist of England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The unionists have also decided that inducements make for a better message than threats.

In June, as the polls narrowed and the pro-independence camp’s momentum grew, Cameron’s Conservative Party announced that it was prepared to cede complete control over income tax within Scotland as well as some aspects of local welfare policy to the Scottish government. Similar enticements of greater autonomy have been offered by the Labor Party and the Liberal Democrats.

For the Conservatives, it was a stunning concession and an embarrassing about-face. Three years ago, their leader in Scotland, Ruth Davidson, warned that devolution, as the process of decentralization is known, had reached a “line in the sand” and could go no further.

Now, if anything, devolution has been accelerated.

“The three unionist parties know that the Scottish electorate [is] out there saying, ‘We reject independence, but we’re looking to you guys to devolve more powers,’” said Annabel Goldie, a Conservative member of the Scottish Parliament. “They don’t want independence, but equally they don’t want the status quo.”

Early this month, the three major British political parties unveiled a highly unusual joint declaration promising to transfer more powers to Edinburgh no matter which of the parties wins next year’s British national election.

“It would be politically untenable for any of the three unionist parties, if they ended up in a position of government, to deny the Scottish Parliament additional powers,” Goldie acknowledged.

Those powers, to set income tax rates and make more decisions on social spending, would add to an already impressive Scottish government portfolio.

As it is, Scotland runs its own health, education and legal systems largely free of interference from London. This produces some notable disparities between Scotland and the rest of Britain. For example, higher education remains free here, whereas universities in England and Wales charge students up to about $15,000 a year (an amount British parents find shockingly expensive). Salmond has vowed that “rocks would melt in the sun” before his government introduced tuition fees.

But he and his fellow campaigners have had to make compromises of their own to try to persuade Scots to take the leap to independence.

Salmond’s Scottish National Party, which once suggested switching to the euro as the currency of an independent Scotland, now insists it will keep the pound as well as other reassuring symbols of British-ness, such as the monarchy and the BBC. In other words, independence need not mean a complete break with the familiar, campaigners say.

“The referendum has forced them to define exactly what they mean by independence, and it’s clearly not the independence of a classic 20th century nation-state,” said Nicola McEwen, a political scientist at the University of Edinburgh. “Everyone’s trying to capture that middle ground.”

That may partly explain the narrowing in the polls. The most recent poll, released on Aug. 15, placed the “No” campaign at 51%, with those in favor of breaking away at 38% and 11% undecided. Respondents leaning toward keeping Britain intact cite concern about Scotland’s competitiveness in a globalized economy, the uncertainty over its continued use of the pound and the benefits of being part of a country that routinely punches above its weight on the world stage diplomatically and militarily.

McEwen said pro-union victory by a 10-percentage-point margin probably would be seen as decisive. But that still would point to large numbers of Scots yearning for greater control over their destiny. Greer, the independence activist, said that new powers granted by the government in London would only stoke that desire.

“The more power Scotland is given, the more the question is asked, why are we not capable of the powers still held back?” he said. “Why can’t we run our own foreign affairs, why can’t we run our own defense, why can’t we run our own immigration policies?”

“This debate, no matter what, has resulted in tens of thousands of new campaigners who aren’t going to stop campaigning to build a better Scotland.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.