Deep cleaning: Cave lovers help remove grime left by park tourists

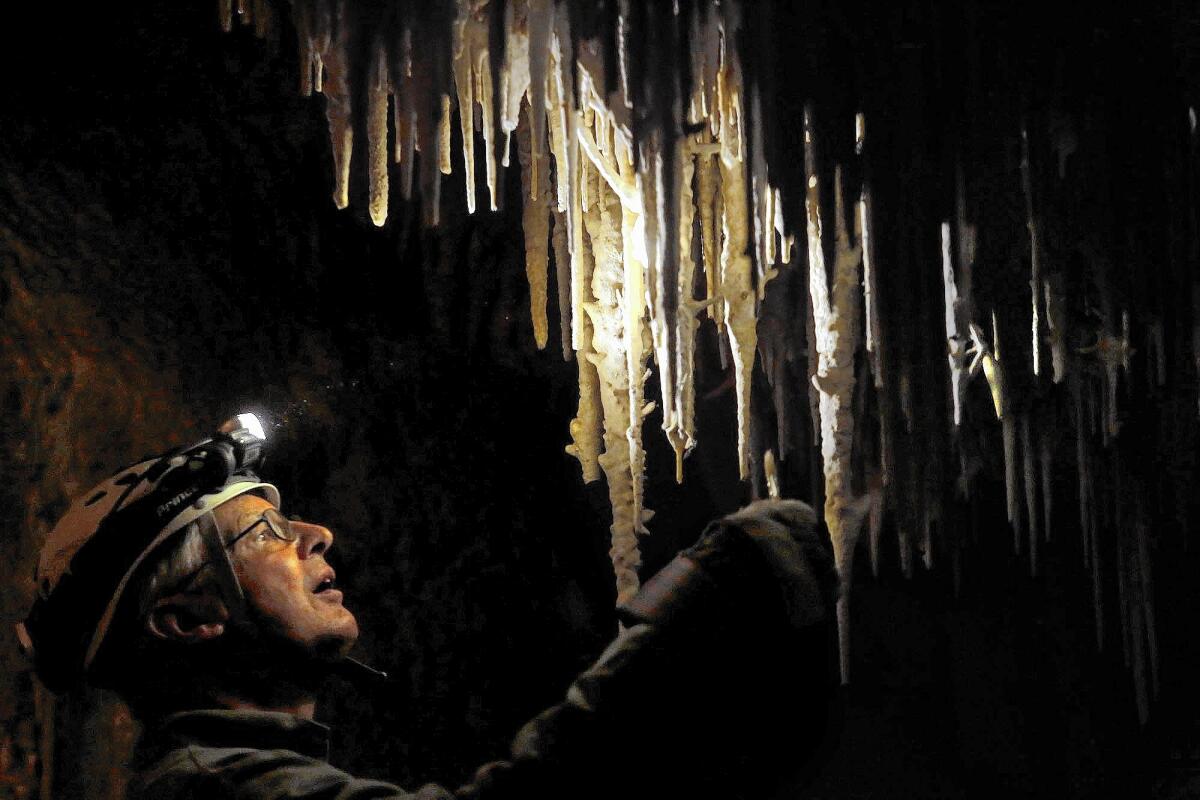

Down here in the subterranean stillness, the beam from Paul Kemp’s headlamp slices through the gloom like a lighthouse beacon — his tool to unearth evidence of the invaders who have long descended into this alien world.

With the studied care of an archaeologist, the 67-year-old retired rocket engineer uses a tiny brush to gently clear away the brownish fluff and grit coating a clutch of stalactites hanging from the ceiling of Lehman Cave.

It’s man-made grime — clothing fibers, hair, dead skin and dust left by 28,000 annual visitors — and it’s everywhere. He carefully collects his catch in a blue dustpan and puts it in a plastic bag the size of an office wastebasket. It’s filling fast.

“Oh, my God,” Kemp says. “These formations are terrible. They’re simply covered with dust.”

Kemp and his 14-year-old son, Simon, are volunteers in a National Park Service program known as Lint Camp, performing one of America’s most bizarre natural housekeeping chores: cleaning a handful of caves popular with throngs of tourists.

The father-son duo from Sandy, Utah, had joined several cavers who abandoned the warm outdoor sunlight to wend their way into this ethereal void of mysterious shapes and shadows. They entered a funeral-quiet temple of limestone and marble where the temperature remains a cool 52 degrees and where bats often lurk, not to mention pseudo-scorpions (without stingers) and tiny armored springtails that rarely see natural light.

Wearing kneepads over their jumpsuits, the pair duck beneath low-hanging thresholds to reach a bedroom-sized area known as the Wedding Chapel. There, the elder Kemp hops atop a ledge to reach toward a strange galaxy of ancient formations more than a million years in the making — not only stalactites and stalagmites, but others with names that evoke their color or shape: cave bacon, draperies, shields and popcorn.

A slender 6-foot-3, Kemp resembles an angular butler delicately wiping down a chandelier long overdue for a dusting. Backlit by the cave’s ceiling lights, dust particles hang in his headlamp beam, barely moving in the stillness.

“Wow,” gushes volunteer Randi Poer, a Santa Ana mother of three. “Paul hit the lint mother lode.”

Each year, scores of cave freaks, spelunkers and speleologists gather at Carlsbad Caverns National Park in New Mexico, Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky and here in Nevada to pick and wipe away buildup that can threaten both the formations and the cave’s inhabitants.

The cave — part of Great Basin National Park, in the desert outback between Las Vegas and Salt Lake City — was officially discovered in 1885 by prospector and miner Absalom Lehman, but many believe Native Americans used the cavern eons before that.

Lehman and later caretakers offered candlelight tours long before the cave became a national monument in 1922. But there have been other intruders: During Prohibition, Lehman Cave served as a secret speakeasy — complete with a dance floor. Federal officials later used the two-mile-long cavern, 200 feet below ground at its lowest point, as a well-stocked Cold War fallout shelter.

Lehman Cave has suffered other indignities. Officials once brought in masses of sandbags to protect formations as they dynamited away walls for a new pedestrian exit. That left sand everywhere.

Every so often, the cave must be emptied of such detritus, like scraping clothing lint from a dryer filter. During last month’s three-day Lint Camp, two dozen volunteers from three states hauled out more than a ton of debris — including tarmac and concrete chunks from paths removed during cave restoration work.

Visitors are not allowed to touch the formations, but fibers, skin cells and hair waft through the air and build up anyway. Ben Roberts, the park’s chief of natural resource management, calls lint a human problem that humans must clean up.

“For me, it’s an aesthetic,” he said. “My philosophy for caves is just like any camping trip — if you pack it in, you pack it out.”

Like a below-ground construction crew, the volunteers trudge deeper into the earth. They wear miner’s helmets and carry large white Benjamin Moore paint cans filled with brushes, gloves and tweezers, clanking along inside a peaceful realm where uneven walls echo their movements.

They enter an environment that provides a glimpse into the planet’s ancient past, which one park brochure describes as “shadows, strange shapes and a feeling of the long passage of time.” Cartoonish stalactites dropping from above and stalagmites rising from below often meet in the middle to form ragged, skinny columns.

Some deposits are broken, the legacy of an era when cave visitors believed that “If you can break it, you can take it.” Remaining shapes resemble hobbits, tiny Buddhas, jellyfish, seahorses, Chinese mandarins and elephant tusks.

It’s a Friday morning and just eight cavers are here; another 20 will arrive the next day. The group pauses at the intersection of two routes. Roberts leads some for the more substantial restoration work, while park ecologist Gretchen Baker addresses the three remaining cavers.

“Lint pickers,” she says, “follow me.”

Park workers explain the rules: Don’t touch anything without gloves; moisture and oils from human skin can alter the growth of the delicate formations, already glacial at one inch a century. And no food — one dropped crumb could cause an explosion of bacteria, disturbing the cave’s fragile ecosystem.

As Baker’s group settles in, she suggests a contest to see who can fill the most bags of dust and lint. This is detail work that often requires a magnifying glass and tweezers when the lint has become moist and sticks to the formations like cobwebs. The volunteers start slowly, nervously touching the rock as though petting a skittish cat.

They quickly get the hang of it, and start talking about themselves as they rub, pick, dust and polish. In the summer months, water trickles in the cave, which is mostly dry on this winter day. Still, the place feels damp, evoking goose bumps.

Poer, a petite Orange County circuit board designer who began caving in 2001, asks, “How clean do I need to make this?”

“Don’t go OCD,” Baker says. “Just the major stuff.”

Adds Poer, “I just don’t know where to stop.”

As she brushes off the lint, the formations seem to come alive. No longer a dull bone color, many seem to sparkle — a marble face-lift in the making.

“This looks so much cleaner!” Poer says. “I can see the figures now. They look like coral!”

Baker, an Indiana native and 14-year park veteran, works alongside the crew: “I should give as much attention to my house.”

Poer talks about spelunkers: “Cavers are really strange. There’s a lot of nerds in this sport.”

Paul Kemp looks up, contemplating a response. “There’s an awful lot of passion,” he finally says.

Here and there, the cavers encounter graffiti left behind from the 19th century, including one simply inscribed “N. Luna 1896.” At previous Lint Camps, volunteers have recovered pennies, nails and buttons dating back 130 years.

Finally, the contest results are in: Simon Kemp, a shy boy as tall as his father, has filled four bags.

“Simon!” his dad exclaims. “You upheld the family honor!”

Twitter: @jglionna

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.