Op-Ed: LBJ’s second great battle: Enforcing the Civil Rights Act

When Lyndon Johnson became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, so closely had he played his political cards that nobody was exactly sure what he believed in. Very quickly, the surprising answer became clear: civil rights. Johnson went all-in on Kennedy’s stalled bill, declaring: “What’s the point of being president if you can’t do what you know is right?”

Eight months later, on July 2, after the defeat of the longest filibuster in Senate history, Johnson signed the 1964 Civil Rights Act into law. LBJ and his Senate allies, especially Minnesota’s Hubert Humphrey and Montana’s Mike Mansfield, deserve all the credit they get.

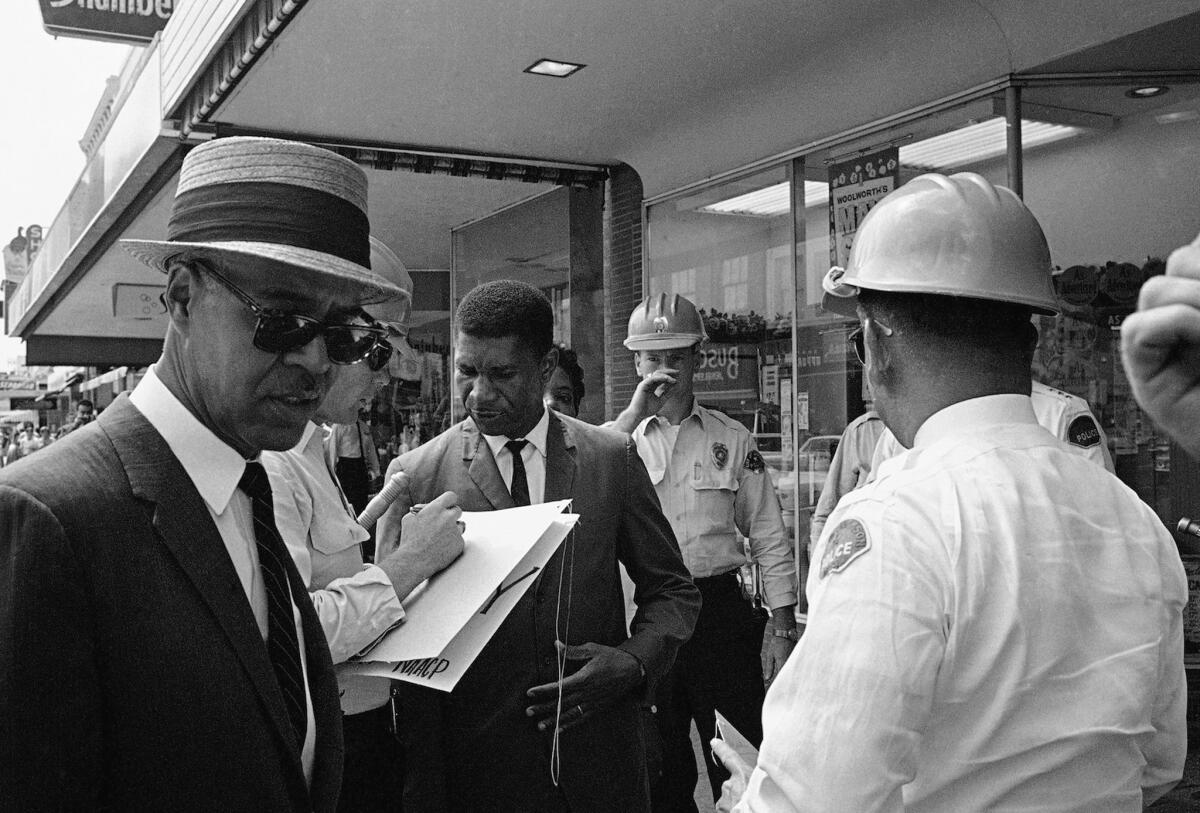

But of course the real heavy lifting had been done by civil rights leaders such as the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Roy Wilkins, Bob Moses, James Farmer and their weary, long-suffering foot soldiers. The Civil Rights Act was the culmination of decades of bitter struggle and very real sacrifice. Only 11 days before Johnson signed the act, three young Freedom Summer volunteers disappeared in Mississippi. The bodies of James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman would not be recovered for another month.

Jim Crow segregation had endured because of local violence on the ground and political ruthlessness in Washington. For almost a century, a coalition of Southern Democrats (the Dixiecrats) and Midwestern Republicans had beaten back every attempt to fulfill the promise of the 14th and 15th Amendments. The lone exception, the Civil Rights Act of 1957, passed under LBJ’s stewardship as Senate majority leader, was declared a victory by the New York Times, but the NAACP’s Wilkins likened it to “soup made from the bones of an emaciated chicken which had starved to death.”

Not so the 1964 bill. The courtly and unreconstructed segregationist Sen. Richard Russell, leader of the Dixiecrats, recognized the very real threat the bill represented and vowed that his forces would fight “with our boots on, to the last ditch!” They lost, but LBJ recognized the political price that his side would pay, telling one of his aides, “The Democratic Party just lost the South for the rest of my lifetime and maybe yours.”

But Jim Crow began to die, in part because LBJ well understood that passing laws was one thing and enforcing them quite another. Just as he had been determined to muscle the bill through Congress, Johnson was determined to see the law carried out by every executive power at his command.

Title II (public accommodations) of the act overturned state and local segregation laws, and the Supreme Court helped by upholding its application to the private sector through the commerce clause.

There had been chilling resistance in some quarters. In Jonesboro, La., that summer, the public library and swimming pool remained off-limits to blacks, and when local youths protested, 40 of them, and some of their parents, were arrested. To drive the point home, the Ku Klux Klan paraded through the black neighborhood in full regalia, carrying guns, led by a sheriff’s patrol car.

Both sides began to arm themselves, and a very real race war was only averted by a federal injunction and the personal intervention of administration officials, including Humphrey, who by then was vice president.

Title VII (workplace discrimination) created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Women had been given special protection under the new law, not out of any moral imperative but as a poison-pill amendment introduced by Virginia Rep. Howard W. “Judge” Smith, who hoped that Northern senators sensitive to union concerns would not support a bill that granted women equal rights. He was wrong. And to everyone’s surprise, Title VII would profoundly alter the legal and cultural landscape for women as well as blacks.

Title VI (discrimination in government-funded activities) was even more immediately successful. Swift directives from the White House to the Department of Health, Education and Welfare to cease giving federal dollars to segregated hospitals transformed facilities overnight. Where moral suasion had failed, the threat of defunding worked wonders.

Similarly, a quick ruling by U.S. Commissioner of Education Francis Keppel announced the withholding of federal funds ($4 billion) from school districts in 17 long-segregated states. In one year, there were more public school desegregation commitments than had been achieved over the previous decade. To ensure this was more than lip-service, the Office of Education developed objective, quantifiable measures to evaluate progress.

In 1965, the Voting Rights Act was the final nail in the coffin of Jim Crow. Six days later, Watts erupted in violence, the first in a series of urban riots as the long-simmering frustration of blacks trapped in city slums sought release. At the same time, the white backlash and subsequent political realignment that LBJ had predicted was already underway.

The South, once solidly Democratic, would become a Republican stronghold. And the civil rights movement would meet its Waterloo not in Southern cities but in Boston and Chicago, where Northerners would discover that the limits of their racial tolerance ended in their own neighborhoods. Politicians who could no longer get away with using the vilest excesses of racial language communicated in coded but comfortable phrases like “law and order” and the “intrusive federal government.”

Today, even after the election of a black president, men and women of color still suffer disproportionally against almost every measure of American life. So how should we feel about the 1964 Civil Rights Act? We should feel proud of an achievement that brought us closer to the founding ideals of this country. We should feel humbled by the sacrifice of millions of people over decades of hard and painful work to bring that change about. And we should feel challenged because the work is not yet complete.

Robert Schenkkan’s “All the Way,” about Lyndon Johnson and the battle to pass the Civil Rights Act, won the 2014 Tony Award for best play. Its sequel, “The Great Society,” premieres in July at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.