Great Read: Four-decade obsession turns junk ’54 Ferrari into pricey gem

In 1968, college teachers Charles Betz and Fred Peters went to look at a busted-up Ferrari a fellow car collector was selling for $1,100.

A wreck had destroyed the body of the 1954 375MM Spider convertible. The engine was missing. The chassis had been chopped and shortened.

The price was too high. But the Spider came with an extra set of wheels, and Betz had seen Dan Gurney race the car — capable of speeds over 170 mph — at the 1958 Times Mirror Grand Prix in Riverside. He knew what the car had been, and could be again.

The collectors resolved to find the missing parts, restore the car to its original glory and sell it for a profit. They didn’t know then that the task would take decades, outlast their marriages, compromise their bank accounts, test their patience and ultimately earn them millions.

::

Betz was a Cerritos College economics professor who bought and restored English and Italian sports cars. Peters taught psychology at nearby Fullerton College. He specialized in German cars.

In 1966 they attended a dinner party thrown by a friend, who thought the two professors who loved old cars would like each other.

They did. Each admired the other’s tactics with classic cars.

“He was smart,” Betz said. “Rather than buying impractical cars, like me, he was buying Volkswagens.”

“Charles was more sophisticated than I was,” Peters said. “He was working on MGs and Austin-Healeys.”

They bought and sold Porsches, Jaguars and Maseratis, generally breaking even. They acquired and restored Alfa Romeos, always seeing gold but never turning a profit.

In time, they began to specialize in Ferraris. Through the ‘60s and ‘70s, those cars were relatively cheap, partly because they were hard to work on. Few American mechanics understood them, and Ferrari didn’t provide service manuals.

“The people who owned them had tried to repair them — and failed,” Betz said.

“You could buy a used one for almost nothing,” Peters said.

Almost. The two men were paying $3,500 to $4,000 for each car, at a time when Betz’s college salary was $14,000 a year. Peters was making even less.

::

The partners made some mistakes.

“It was just a hobby that got out of hand,” Peters said.

Often, they had to sell a car to buy a car, or borrow money from Peters’ mother or from finance companies, to close a deal. On several occasions, Betz and Peters put up their furniture as collateral.

“It was a little distressing on my marriage,” Betz said.

Sometimes, they lost money. They bought a Bugatti, but for five years couldn’t make the engine function properly. When they finally sold it, Peters remembers telling the buyer, “It’s a great car. Just don’t try to make it run.”

Trying to be more professional, they opened a used Ferrari dealership in late 1968. That lasted two years.

“Everyone wanted a new Ferrari — not a used one — so nobody liked us,” Betz said. “The bank didn’t like us. The insurance company didn’t like us. Nobody likes you if you’re in the used Ferrari business.”

Sometimes they turned a small profit. In 1970, someone paid $5,500 for a Ferrari Berlinetta they’d acquired for $5,000.

Later that year, they paid $4,000 for a Ferrari 250 Lusso that needed a new engine. Six years later, they sold it for $12,000.

“Now we thought we were major capitalists,” Betz said.

The men began to formulate what he called a “30-year-plan.”

“We decided we wanted to each have a nest egg of $300,000 when we were done,” Betz said. “The people who knew us thought we were crazy — including our wives.”

They kept their day jobs, but their side business continued to grow. They moved out of their garages and into a rented industrial space. Soon they were restoring a dozen cars at a time.

Their families grew too. Betz, married twice, has four children and three grandchildren. Peters, divorced, has three children, four grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

All the while, they were patiently trying to acquire the missing pieces of the 375MM.

Ferrari made only 14 of the 375MM Spiders, and two are known to have been destroyed. Still, always asking around, the men found a door, then a door pull, then other parts.

Another collector had many of the key elements from the original car. But he refused to sell. Betz and Peters waited him out, and worked on other vehicles. Ferraris, meanwhile, started commanding higher prices. (The 250 Lusso that Betz and Peter sold for $12,000 changed hands again 10 years later for $80,000 — and would sell a few years after that for $580,000.)

Ferrari parts also got expensive. A pair of original headlights for the 375MM cost $5,000. An exact replica of the grill cost $10,000.

But profits were going up too. The two men began making money from selling parts they’d collected, but didn’t need for their own cars. They also sold cars for what seemed astronomical sums.

In 2002, the pair sold a rare 1957 Ferrari Testarossa they’d spent years restoring. Though the men are reluctant to identify the buyer, or name the sale price, it was their first really big score.

“My half of the profit on that car was more than I made in 38 years as a college professor — in my entire career as a college professor,” Betz said. “So, we did all right on that one.”

::

No matter what they bought, sold or traded, they held onto the 375MM.

In 1986, the collector who owned the original parts decided to sell — not to Betz and Peters, but to the English Ferrari restorer David Cottingham.

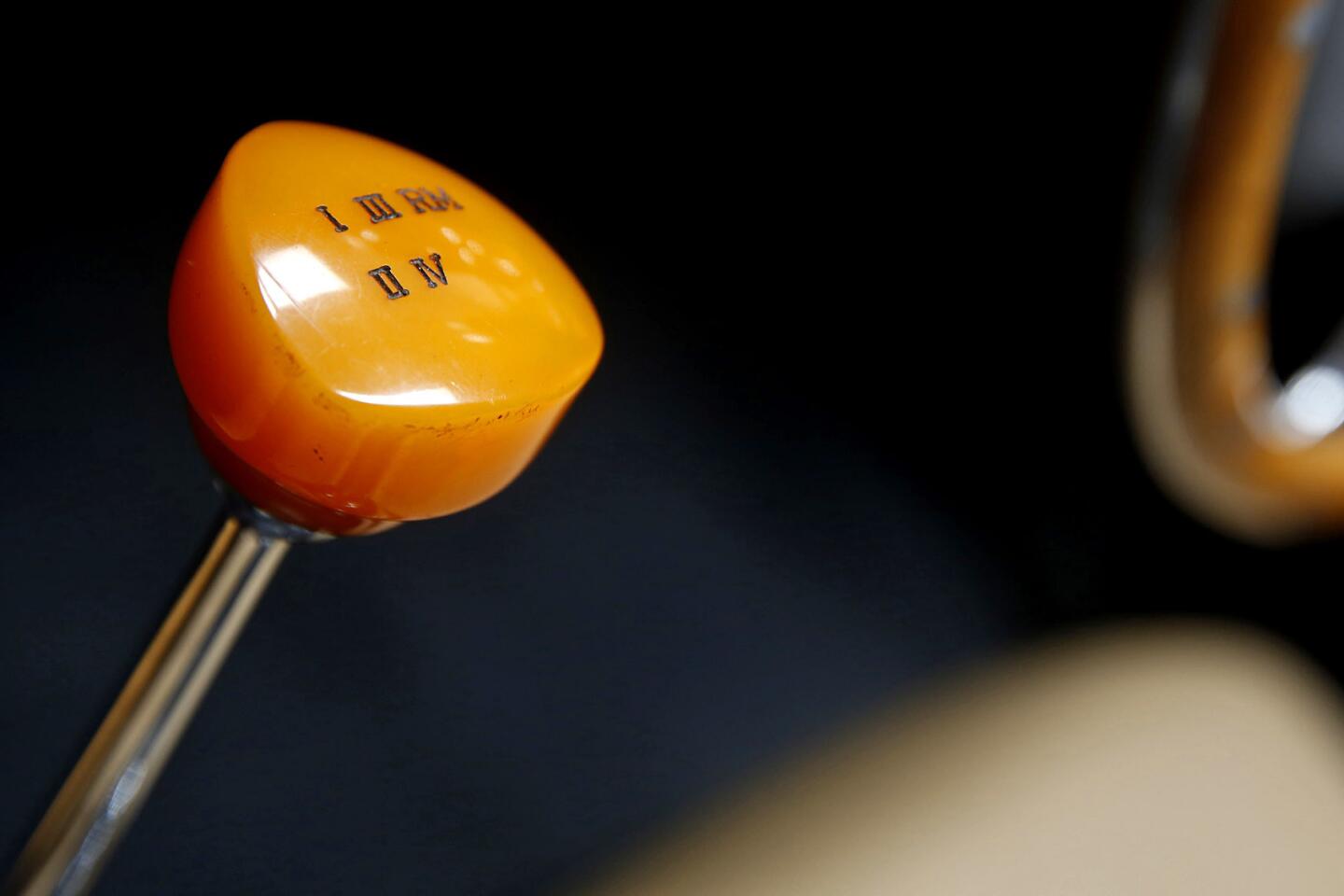

The partners were friendly with Cottingham, and he agreed to let them look through the inventory before he shipped it back to England. Among the many old parts Peters and Betz eagerly bought were the car’s original gas tank, shift knob, hood and passenger seat.

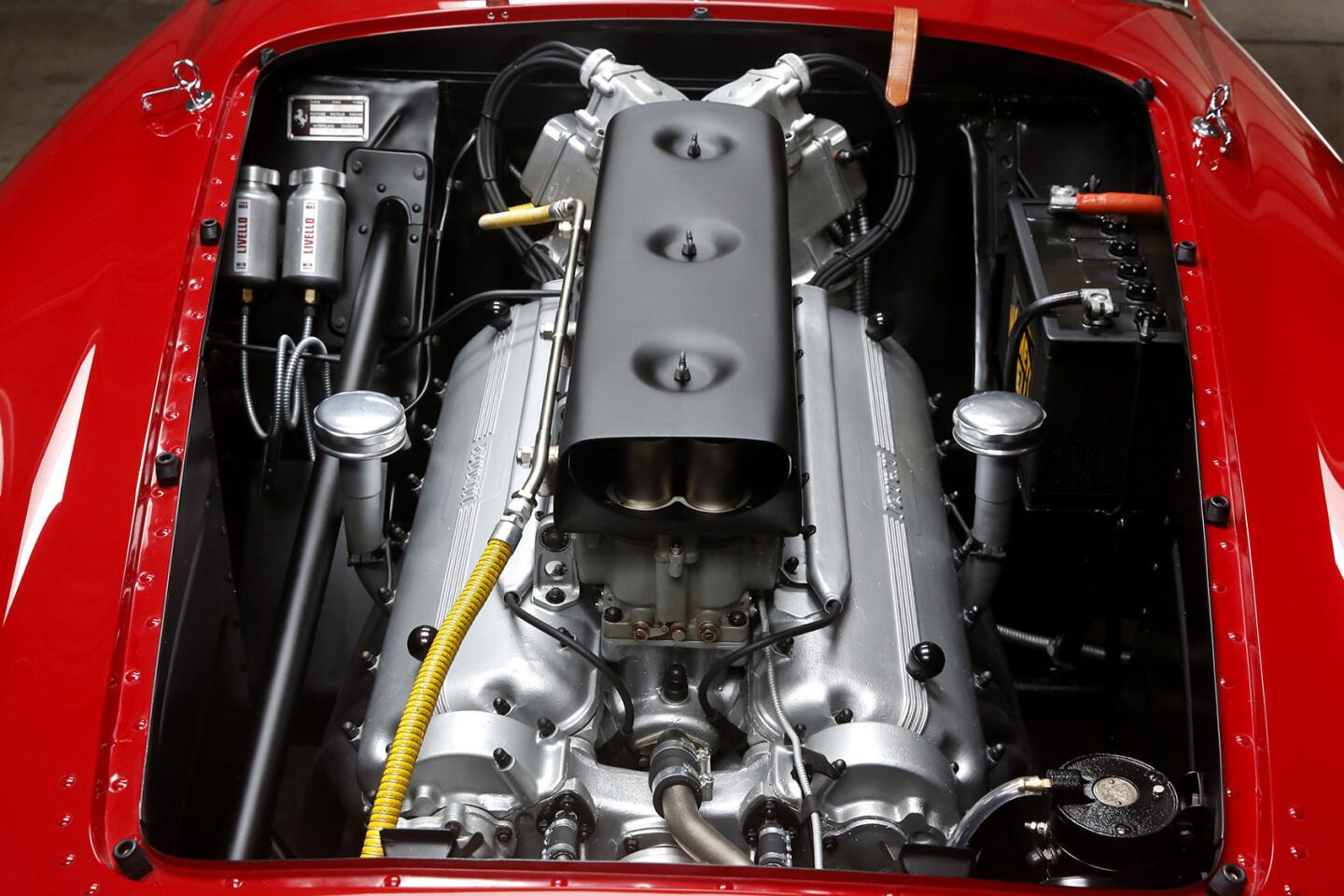

The final phase of the 375MM’s restoration began. The frame was rebuilt, the engine reassembled. The body was repaired, the paint reproduced.

Betz’s son Brooke, who now does much of the work on the partners’ cars, estimated the men put $400,000 into the engine alone, and at least $1 million in other parts.

After more than four decades, the car was showroom ready — Ferrari-red paint gleaming, 12-cylinder motor firing, chrome wire wheels shining. The wood of the steering wheel, the leather of the seats and even the leather straps of the hood latches were restored to factory perfection.

In early 2014, the two men decided it was time to sell. They were ready to liquidate the collection they’d spent almost five decades assembling.

“When you’re 75, and your partner is 83, you can’t have a 30-year plan,” Betz said.

In August, the two men put the 375MM on a flatbed truck and shipped it to Monterey, where during the annual Car Week it would go up for sale at an event conducted by the Mecum auction house.

Peters and Betz had reason to be optimistic. The week had already seen some record-breaking sales. A 1962 Ferrari 250 GTO had sold for $38.115 million — the highest price ever paid for a car at auction.

That hot, dry afternoon, the partners, along with Brooke, watched as collectors feverishly bid for their car — and then stopped before reaching the sellers’ stated minimum. The top offer came in at just under $5.8 million.

It was tempting, but not enough.

A tired-looking Peters, wearing jeans, suspenders and sandals, stroked his wispy white goatee. Betz, in baggy shorts, sneakers and trifocals, sighed and shrugged his shoulders.

“In terms of what we’ve spent, we would have been way ahead,” he said. “But we’ve owned it for 46 years, and $5.8 million just won’t do it.”

::

Back in Orange, where the partners store the 375MM and six other classic cars left in their collection, Peters and Betz continued to get inquiries. An unidentified collector had made an offer for the 375MM, but was unable to find buyers for the cars he needed to sell to raise the money. Another offered the same price, but couldn’t finish the financing.

The men seemed almost relieved.

“The good news is that we like the car well enough to keep it,” Betz said.

The car did look pretty good, all fixed up, sitting in the garage, Peters said, and selling their restored cars always came with “a little twinge.”

“You put your heart into these cars,” he said. “You remember what they were.”