Parents in Mexico wait, and hope, as mass graves probed

Angry, desperate parents on Monday demanded the safe return of 43 missing university students, even as officials indicated that at least some were probably killed and dumped in mass graves.

Twenty-eight bodies were recovered from a string of hidden pits over the weekend outside the city of Iguala in Mexico’s Guerrero state, and authorities were working to identify them through DNA and other tests.

The students, all of them freshmen, went missing Sept. 26 after they were attacked by Iguala police. They constituted about one-third of their school’s first-year class.

Many of the parents, who gathered at the university, refused to accept that their children were dead, and they blamed their disappearances on the state government.

“We will not rest until we find them,” one bereaved father in a baseball cap said of his missing son. He declined to give his name out of fear. “We are desperate people capable of doing anything to find our children,” he said before breaking down in sobs.

Manuel Martinez, a spokesman for the families, announced plans for a nationwide march Wednesday, which he vowed would “paralyze” Mexico. “We know they were taken away by police,” he said. “We want them back alive.”

Guerrero state prosecutor Iñaky Blanco said the investigation thus far had established that a police officer ordered the students detained and that a local drug boss ordered them killed. A total of 30 people, most of them police but not the two giving orders, have been arrested.

Blanco said two of the suspects had confessed to killing 17 students and burying them in the graves. There was no immediate explanation for the discrepancy in numbers.

The bodies had been placed on top of branches, and some had been doused with gasoline and burned, according to accounts from people who participated in the search.

In Iguala, a banner appeared, purportedly signed by a drug gang, demanding the release of the arrested police. Later, the federal government dispatched its new gendarmerie to Iguala to assume security control of the city, relieving from duty the remaining local police, disarming them and occupying city hall.

The motive for what could be a mass killing of the students remains mysterious.

Many relatives said they were convinced their children were taken to punish the school, a special type of rural institution for poor students and a bastion of revolutionary political activity.

What is clear is the depth of corruption in local police and government. Guerrero Gov. Angel Aguirre said drug traffickers had infiltrated many of the state’s municipal police forces, and often work in cahoots with local city halls.

Yet the capture and killing of 43 students would be extreme.

The mayor of Iguala took a leave of absence in the wake of the disappearances, and then vanished. He is being sought for questioning along with the city’s police chief.

With outrage mounting in Mexico, President Enrique Peña Nieto went on national television Monday and promised a “profound investigation” to find out what happened and bring the guilty to justice.

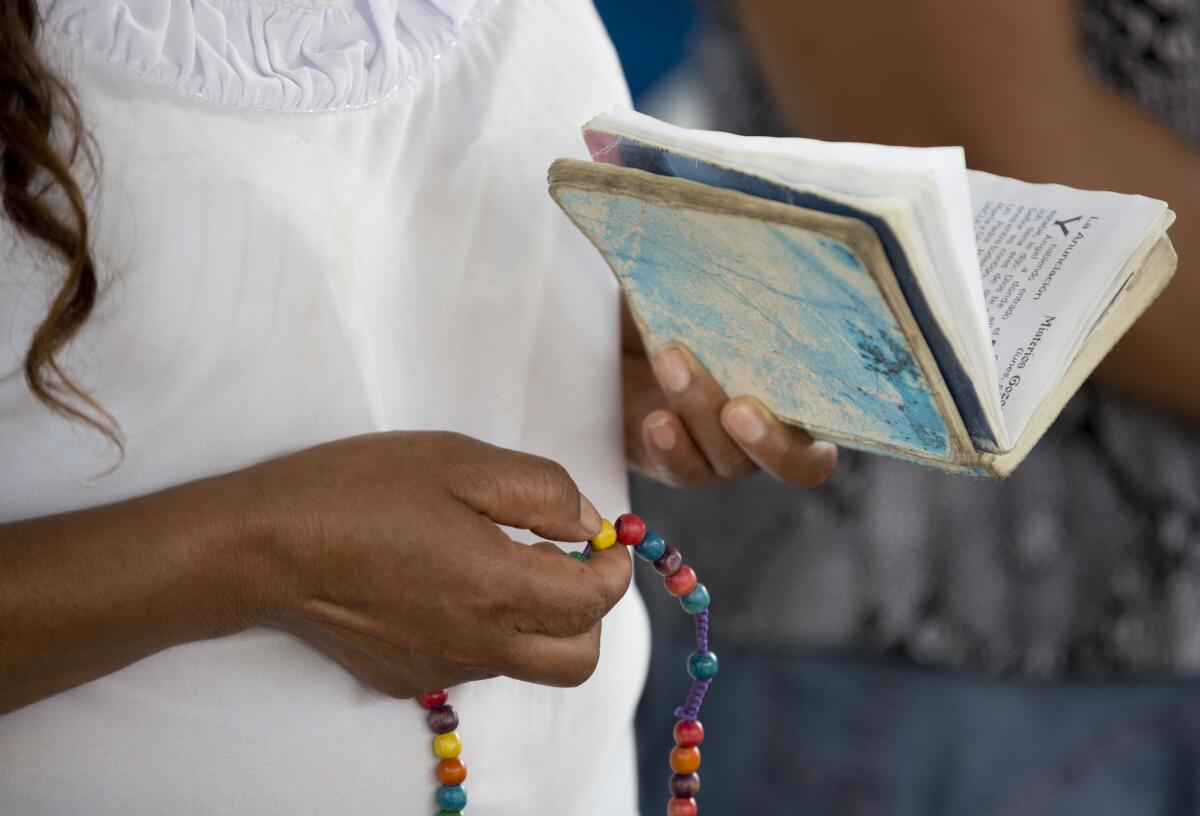

That was no comfort to the families and classmates who gathered in a tree-lined courtyard at Escuela Normal Rural (Normal Rural School) in Ayotzinapa.

“These are not the first forced disappearances and executions that we have had to deal with,” said a member of the group, Javier Monroy, listing the turbulent history of Guerrero, one of Mexico’s most violent states because of drug traffickers, guerrilla insurgencies, a vigilante movement and the normalista students who often clash with authorities.

“We are governed by a society of drug traffickers,” Monroy said.

“What they do is they criminalize protest,” said another father, who also declined to give his name. “They go after students, and the real delinquents are in the government.”

Reflecting the depth of mistrust, the families and their supporters said they would not accept the government’s identifications of the bodies. They have asked a renowned team of Argentine forensic investigators to conduct tests, which they expect to begin in about two weeks.

For Jose Luis Luna, 21, and many young people like him, the “normal” university is the only opportunity for higher education that impoverished children of campesinos are likely to have.

He begged his mother to let him attend, she recalled Monday. “He just wanted to study. We are very poor and he just wanted to help his family get ahead,” the mother, Macedonia Torres, 50, said. She is a widow and earns a little money selling corn and peanuts. Jose Luis was her youngest. He is among the 43 missing.

“I was afraid to let him go off to school,” Torres said, weeping. “And look what happened.”

Follow @TracyKWilkinson on Twitter for more news from Latin America

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.