Op-Ed: Earthquakes pose a hazard to much of California’s fresh water

We dodged a bullet this time.

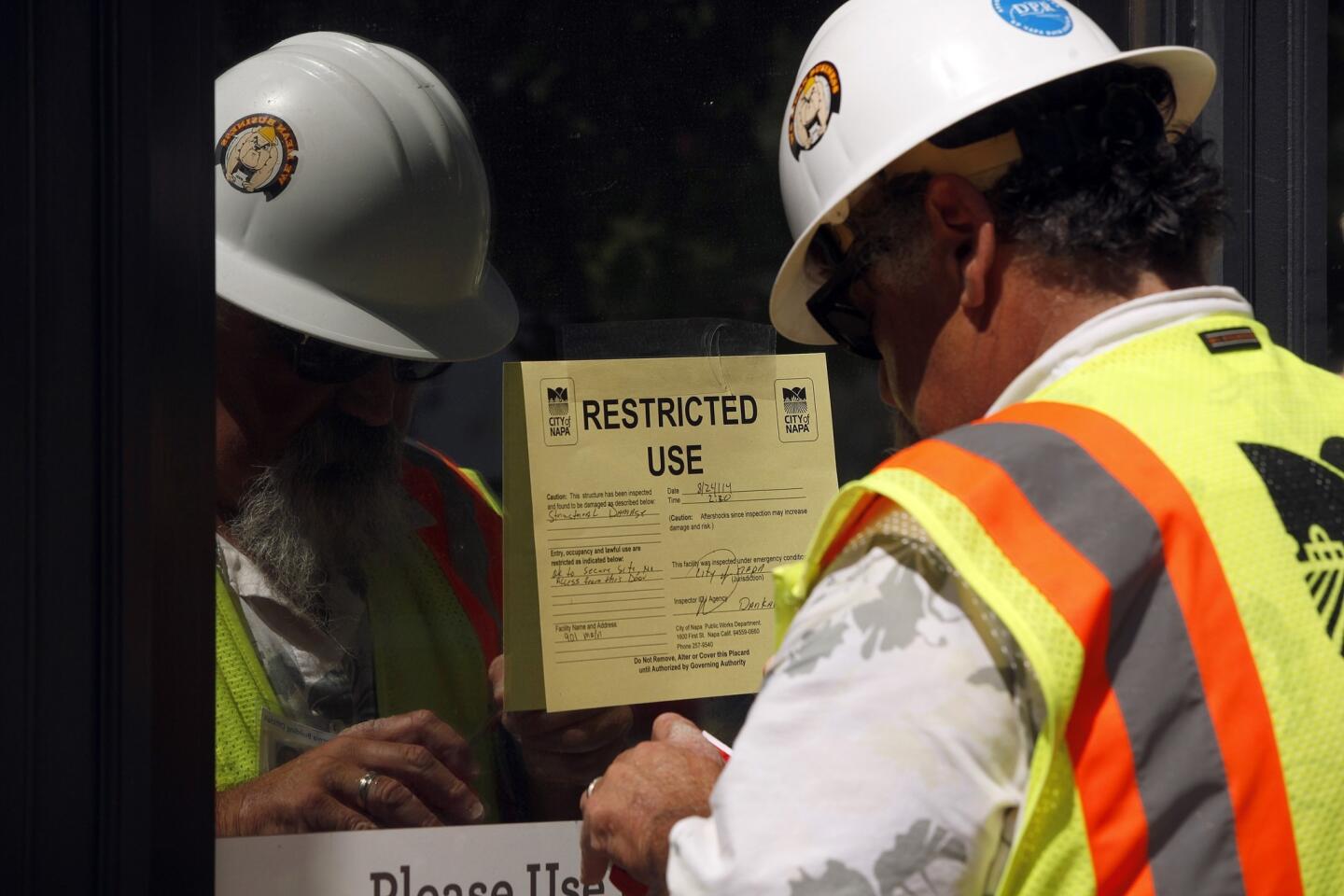

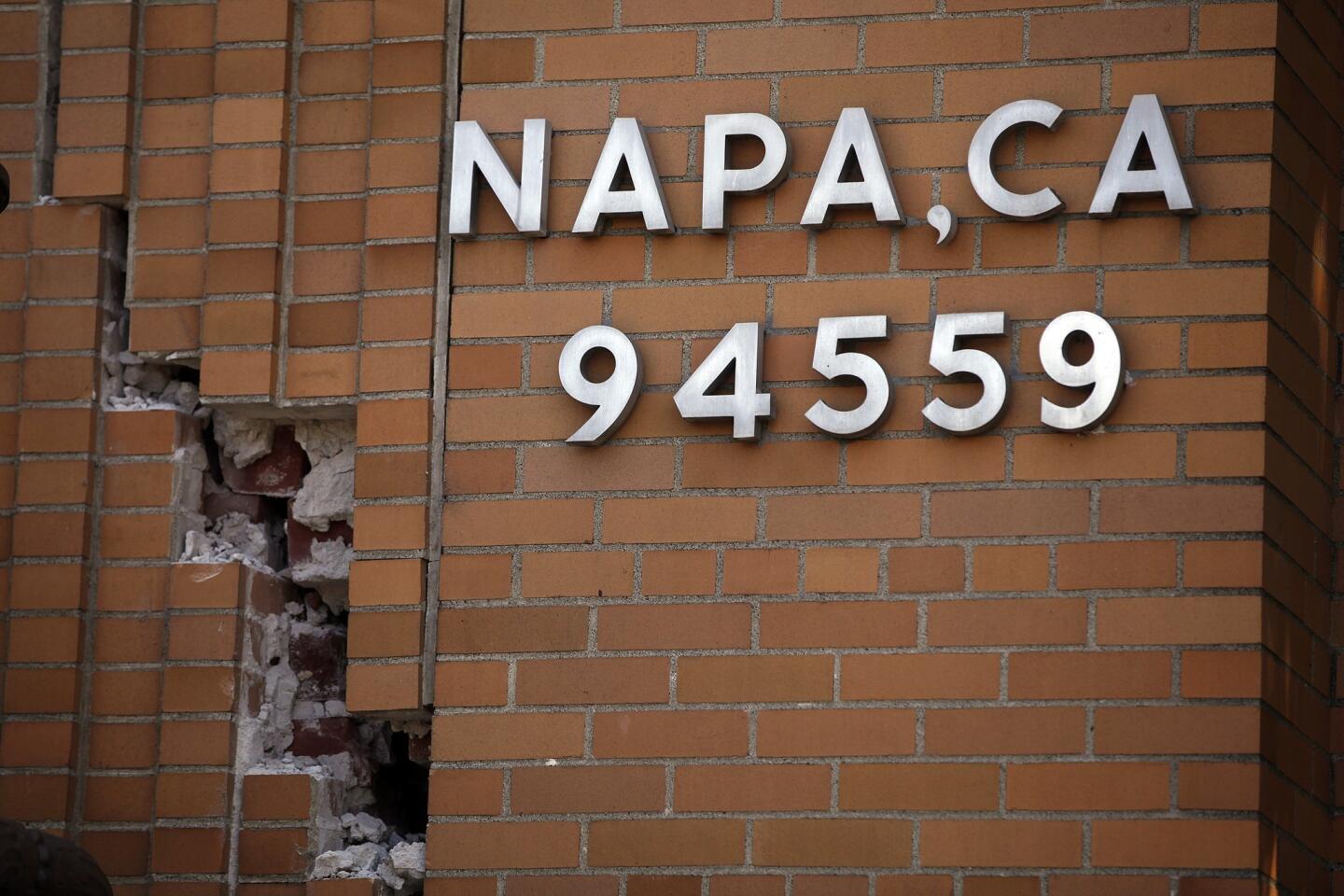

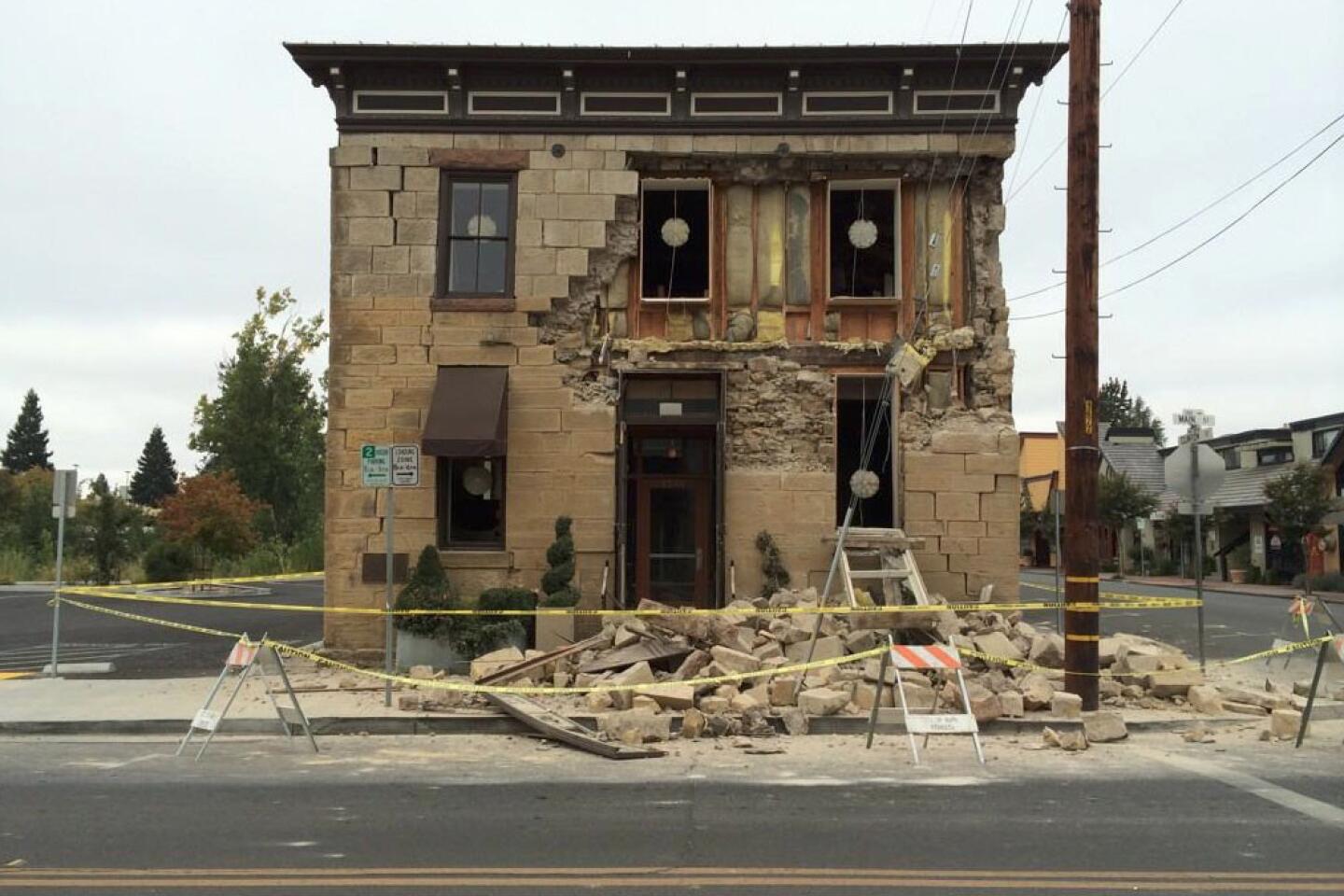

Had Sunday’s magnitude 6.0 Napa earthquake been located a few miles to the southeast, it could have caused a severe shortage of fresh water felt up and down California, exacerbating the effects of our historic drought.

The Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, a short drive from Napa, is the hub of the state’s water distribution system, delivering fresh water to more than 25 million residents and 3 million acres of farmland. Delta water conveyed through a network of levees is crucial to Southern California, the Central Coast, parts of the Bay Area and much of the Central Valley. The drought has significantly curtailed water export, and salt water has intruded into parts of the delta as a result of reduced fresh water outflows.

Islands in the delta are formed by land that has subsided as much as 30 feet below sea level because of the construction of levees around their perimeter and reclamation of delta land for agricultural use. Levee construction began about 150 years ago by dredging soil from adjacent channels, and placing it in an ad hoc manner.

Many of these unengineered levees have only a few feet of freeboard (distance from water level to top of levee) at high tide. A breach of a single segment within a levee system will inundate the interior island. The vast open space within the delta islands exceeds the immediately available volume of fresh water.

Accordingly, simultaneous flooding of multiple islands would draw in saline water from San Francisco Bay, contaminating the fresh water supply for California’s water projects. With insufficient fresh water reserves to flush the salt out of the delta during our historic drought, delta water could remain salty for years.

The findings of engineering consultants and university research show that this catastrophic scenario might very well have occurred had Sunday’s earthquake struck near or beneath the delta.

Strong shaking from a nearby earthquake can cause saturated, loose, sandy soils to behave temporarily like a liquid (a process called liquefaction). Some delta levees are built of, or are founded on, sandy soils vulnerable to liquefaction, and as a result the levees could settle, slump and spread, probably leading to a catastrophic breach.

Exacerbating the risk, many delta levees are founded on peat, soil that is composed of organic material. Peat is highly compressible and soft, and it is known to be capable of shaking strongly during earthquakes. Peat does not experience strength loss like liquefiable sand, but recent research shows that it is vulnerable to settlement after strong shaking, which would reduce freeboard and contribute to the risk of breach.

This is the subject of ongoing research because it is important for engineers to understand the diverse array of hazards that threaten our levees.

Seismically induced failures of levees are not the product of imaginative speculation. They have been observed elsewhere around the world (mainly Japan) where earthquakes, often close to the magnitude of the Napa event, have occurred near major levee systems.

We ignore the potential for seismic failure of levees in California at our peril. We must do all we can to prevent these catastrophic failures from affecting our water supply. Let’s heed the warning that Sunday’s earthquake provides by adopting a long-term solution to the water conveyance infrastructure problem in the delta.

Scott J. Brandenberg and Jonathan P. Stewart are the vice chairman and chairman, respectively, of the UCLA Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.