Fears of unrest cloud Afghanistan as election dispute drags on

As Afghanistan’s disputed presidential vote nears an uncertain conclusion, fears are mounting that post-election unrest could threaten the fragile political order that the United States has struggled for 13 years to help build.

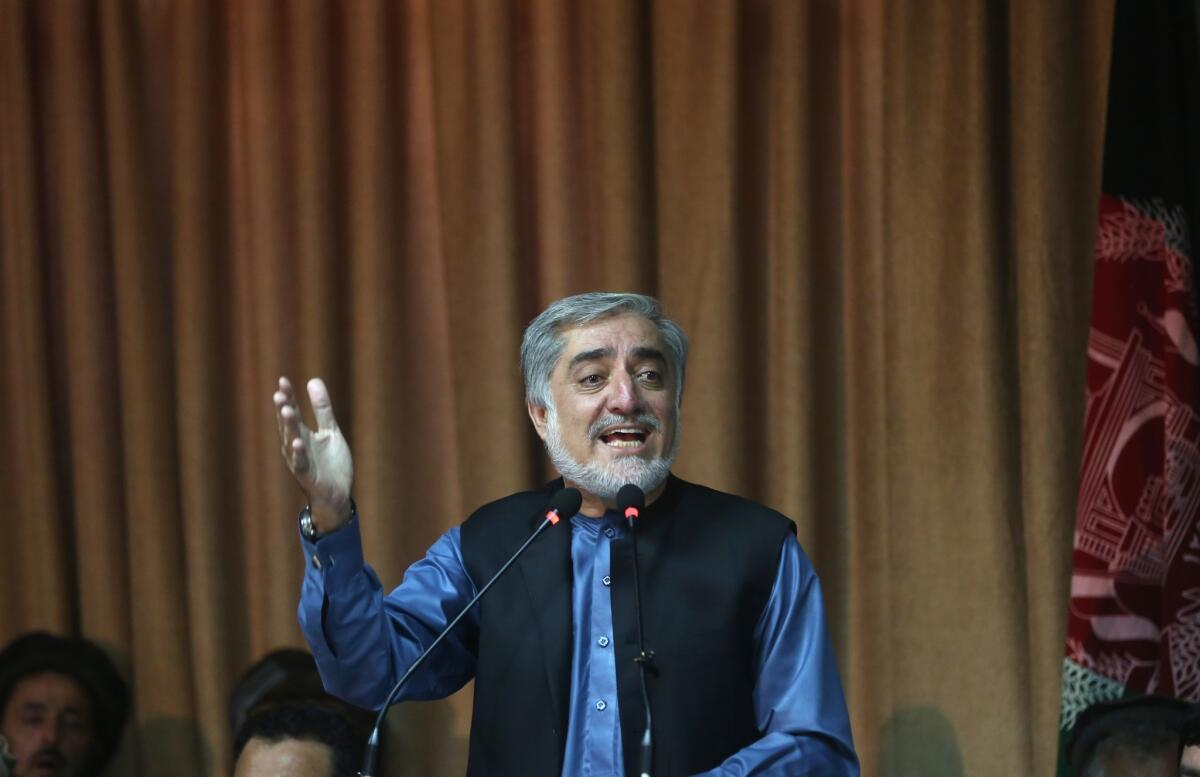

Recent developments have raised questions about the ability of Abdullah Abdullah -- the one-time front-runner who has alleged a conspiracy to rig the results against him -- to pacify supporters if he, as expected, is declared the runner-up.

The concerns have increased as he has clashed with rival Ashraf Ghani over the details of a power-sharing proposal, brokered by the Obama administration, in which the new president would cede some decision-making authority to a chief executive from the opposing camp.

Last week, at an event commemorating the slain Afghan resistance commander Ahmed Shah Massoud, Abdullah had to calm angry supporters heckling a 92-year-old former president who endorsed Ghani. At a busy Kabul intersection named for Massoud, a crowd of protesters chanted, “Death to Ghani!”

Two days later, a group massed outside the United Nations offices carrying signs disparaging the chief U.N. diplomat in Afghanistan, who has overseen a controversial election recount. The protest has prompted outrage from the world body.

One of Abdullah’s running mates, Mohammed Mohaqeq, said over the weekend that if a power-sharing deal isn’t reached, or is seen as being too favorable to Ghani, the Abdullah campaign might not be able to restrain dissatisfied backers.

“We will try our best to manage and control the people not to go the wrong way,” he said at his home in western Kabul. But he added: “What the people’s reaction will be is unpredictable at this point.”

The candidates met Monday with outgoing President Hamid Karzai for the latest round of talks, still reportedly at odds over the authority to be held by a chief executive. Abdullah envisions the holder of the newly created post as having the power to appoint cabinet ministers, including those responsible for security forces, while Ghani believes it should be an advisory position reporting to the president.

As talks have dragged on since Secretary of State John F. Kerry announced the plan in July, many Afghans express fear that tensions could explode into the streets.

“Of course there will be violence,” said Solaiman, a 26-year-old tailor in Kabul, who goes by a single name.

Abdullah said last week that he would not accept the results of the U.N.-supervised audit, which he contended has not eliminated fraudulent votes cast in favor of Ghani in a June runoff election between the finalists. U.N. officials said Sunday that the audit was completed, and Afghan election authorities are expected to announce the results within days.

Zabihullah Jaffari, a painter, said Afghans have waited too long for the candidates to reach an equitable agreement, while unemployment and other economic problems have worsened.

“If they don’t come to an agreement, the poor people who have been out of work for months will have no choice but to take to the streets,” said Jaffari, 46.

The election has taken on an ethnic dimension because Ghani, like Karzai, is a member of the Pashtun community, Afghanistan’s largest, and his running mate, Abdul Rashid Dostum, is a former Uzbek militia leader. Abdullah is more closely identified with the Tajik minority and also enjoys support from the Hazara community.

Some analysts believe that even if ethnic divisions worsen, the rival camps will try to avert major violence –if only to protect their considerable economic interests.

“The potential for a violent rupture between the rival camps poses an enormous risk, but it still seems unlikely to escalate out of control,” said Graeme Smith, Afghanistan analyst for the International Crisis Group. “The powerful men who are now negotiating their places in the next government are very wealthy. Many of them own large parts of Kabul, and I doubt they want to see the capital burn.”

Earlier this month, Atta Mohammad Noor, a key Abdullah ally who is governor of the northern province of Balkh, warned of sweeping street protests if the talks failed to produce a satisfactory outcome. On Monday, Juma Khan Hamdard, governor of Paktia province in the east, who supports Ghani, warned against attempts at destabilizing the country.

“We want to clarify that we are not pro-crisis but if some people intend not to accept the final results and attempt to push Afghanistan towards crisis, we are ready to defend our votes at any cost,” Hamdard said in a statement.

Scattered violence attended last week’s events in memory of the 2001 death of Massoud.

Abdullah, a former spokesman for the Tajik militia commander during the war against Soviet occupation, urged supporters to refrain from violence But a demonstration in Kabul’s Massoud Circle, near the U.S. Embassy, quickly turned angry.

Officials announced later that gunfire in Kabul celebrating Massoud’s memory had killed a 21-year-old man and injured five others.

Last Friday, after pro-Abdullah demonstrators chanted slogans against the head of the U.N. mission in Afghanistan, Jan Kubis, the mission tweeted that it had “grave concerns related to direct threats and verbal attacks against the U.N.”

Mohaqeq, the Abdullah running mate, denied that the campaign was involved in the protest, saying he learned of it later from Facebook.

“What people do,” Mohaqeq said, “is up to them.”

Latifi is a special correspondent. Staff writer Bengali reported from Mumbai, India.

For more news from Afghanistan, follow @SBengali on Twitter

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.