Status of Philae lander uncertain after historic comet landing

The European Space Agency says researchers are still trying to pinpoint the status of its Rosetta probe after it successfully landed on a comet for the first time.

Philae, a mobile laboratory the size of a washing machine, landed on comet 67P deep in space Wednesday morning, but it is still unclear exactly what happened during and immediately after its landing.

"We have landed at the right place. It's also the right comet, don't worry," ESA Director-General Jean-Jacques Dordain joked to a crowd of reporters Thursday evening. But not much more was known about how the lander touched down.

Infographic: Rosetta probe's mission, step-by-step

"It's complicated to land on a comet. It's also, as it appears, very complicated to understand what has happened during this landing.... We still do not fully understand what has happened," said Stephan Ulamec, the Philae lander manager. Ulamec said some initial data from the lander suggest that it may have bounced off the surface of the comet and come back down again, turning slightly. "So maybe today, we didn't just land once, we even landed twice," he said at a news conference.

The agency made space exploration history with even just the one landing. Humanity had slammed spacecraft into comets before, but it had never gently landed on one. Scientists launched the mission to better study the makings of comets, which they believe date back to the earliest days of the solar system.

Photos: Rosetta probe's historic landing on comet

Philae separated from the Rosetta orbiter at 12:35 a.m. PST Wednesday, after a decade of being attached to the spacecraft. Photos transmitted from the main Rosetta spacecraft shortly after it detached included a parting shot of Philae heading toward 67P, and another that shows the lander shrinking from view. It took the lander about seven hours to complete its journey toward the comet, which it had been circling for months.

When it was about two miles away, Philae's cameras snapped a close-up of the comet's surface. Paolo Ferri, the Rosetta mission director, says all the data point to a "very precise first landing" that was "very close to the originally planned" landing site.

The Rosetta probe overcame several potential pitfalls to land on the comet's surface. Even a minute miscalculation in its speed could have meant missing a safe landing, and scientists had no way of steering the probe once it separated. The operation also relied on flawless communication between the two spacecraft, only one of which could send signals to Earth.

The landing was not entirely smooth, however. Two harpoons that were supposed to tether Philae to the comet did not fire, the agency confirmed, and scientists are looking at options to refire them, an operation that in and of itself could be problematic.

This comet-landing expedition has been in the works since 1993, when the European Space Agency green-lighted the project and began designing and building the spaceship and lander with a certain comet in mind. But when engineers found a problem with one of the rockets on the spacecraft, the launch was postponed, and a new target, comet 67P, was chosen.

The Rosetta orbiter spent 10 years chasing 67P through space and has been escorting the comet on its journey toward the sun for the last three months. It will continue to fly with it through 2015, collecting data on what the comet looks like, what it's made of and how much water it's spewing into space.

Rosetta launched in March 2004, traveling through space for seven years until the European Space Agency team put it into a three-year hibernation to conserve energy.

Then, on Jan. 20, alarm clocks on the craft woke it up to prepare it for landing. It has been orbiting the comet since early August, scanning its surface and trying to pick the best landing site.

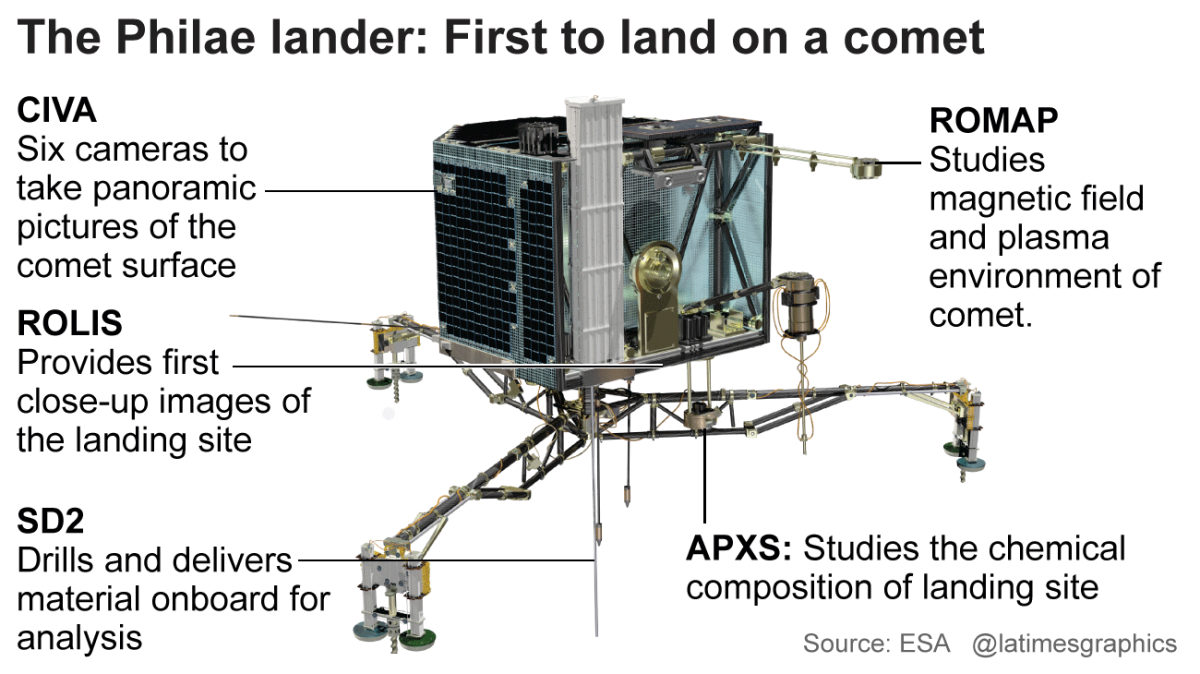

The lander is expected to provide some of the best images yet of a comet’s nucleus, and sensors on its underside are designed to gather data on the texture of the comet’s surface.

The plan for the historic landing called for three mechanical screws on the Rosetta orbiter to start to turn about 1 a.m. PST Wednesday. The Philae lander then detached from Rosetta's side and began a 14-mile free-fall to the surface of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

That free-fall was slow going. The gravity of the mountain-sized comet is just 1/60,000 the amount of gravity on Earth. Scientists estimated it would take the lander between seven and 10 hours to make it to the comet's surface.

On the surface, Philae was to send out two harpoons to keep it from bouncing off. ESA confirmed Wednesday that those harpoons did not deploy, although agency officials said the lander was in great shape and they were looking for ways to refire the harpoons.

Mark Bentley, a scientist with the Austrian Academy of Sciences and a lead investigator on the Rosetta project, tweeted Wednesday that deciding whether to refire the harpoons is "tricky." Because the comet has such low gravity, it is possible the lander could recoil when the harpoons are fired.

Philae sent a message to the Rosetta orbiter to let it know how and where it landed. From there Rosetta relayed the information to Earth, which took 28 minutes to arrive, crossing 300 million miles of space. The message spurred cheers at the command center in Germany.

Scientists had warned that there was a very real chance that the Philae deployment would fail. To function properly, the lander needs to land upright. Unfortunately, the surface of comet 67P is strewn with boulders, and if it had landed on one of those, it could topple.

Scientists are hoping the Rosetta mission will provide answers to a host of scientific questions, such as what comets are made of, if they are responsible for bringing water to the early Earth, what their interiors are like, and why their surfaces are so inky black.

Researchers believe that embedded in the nuclei are materials from the very earliest days of the solar system, and that it is possible the ingredients for life were originally brought to Earth by comets.

Ulamec said scientists are now working hard to interpret the data gathered so far from Philae. Communication with the lander has been cut off for now, as it performs a planned maneuver. Scientists should know more Thursday morning, he said.

But Dordain said he already considers the mission a success. "I don't need to look at computers or data that I don't understand," he said, looking toward Ulamec and Ferri. "When they are smiling, that means it was a success."

UPDATE

Nov. 12, 2:49 p.m.: This article was updated to add information provided by Paolo Ferri, the Rosetta mission director, as well as other details about the comet landing.

The first version of this article was published Nov. 11 at 7 p.m.