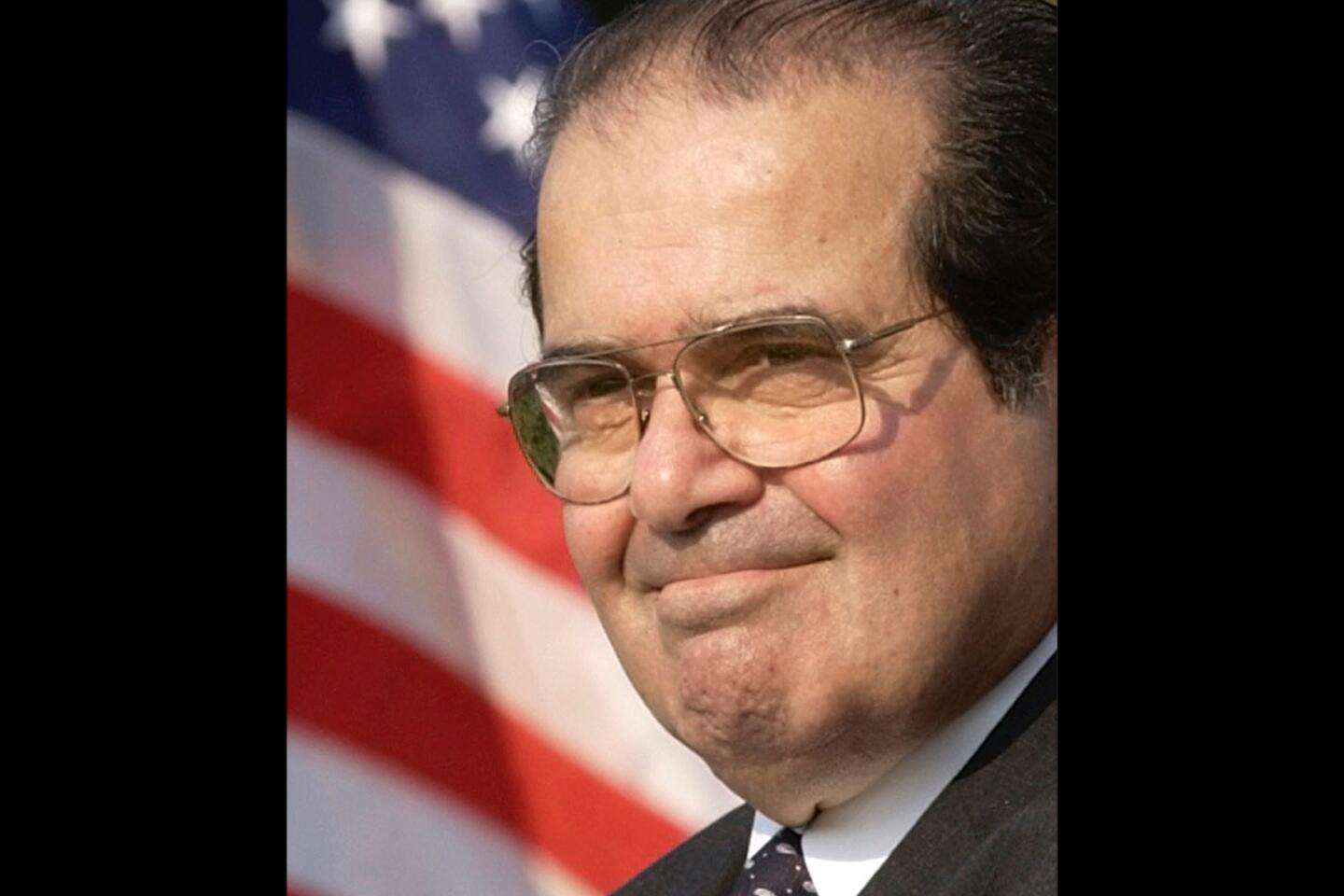

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, an eloquent conservative who used a sharp intellect, a barbed wit and a zest for verbal combat to resist what he saw as the tide of modern liberalism, has died. He was 79.

Scalia died while on a hunting trip in Texas, according to a statement issued Saturday by Texas Gov. Greg Abbott. The death was later confirmed by the U.S. Marshals Service and the Supreme Court.

Scalia was a guest at the Cibolo Creek Ranch, a 30,000-acre retreat of antebellum forts in the Big Bend area of West Texas owned by Houston millionaire John Poindexter.

Scalia had gone to his room Friday night and was found dead Saturday after he did not appear for breakfast, the Marshals Service said.

At about 2:45 p.m. Saturday, people at the ranch summoned a Catholic priest from Presidio, 30 miles away, to administer last rites to the justice, who was a Catholic. “It appeared as though he had passed away in his sleep,” said Elizabeth O’Hara, a spokeswoman for the Diocese of El Paso.

President Obama paid tribute to Scalia as a “brilliant” jurist who “influenced a generation of judges, lawyers and students.” He said Scalia “will no doubt be remembered as one of the most consequential judges and thinkers to serve on the Supreme Court.”

Scalia was a dominant figure at the court from the day he arrived in 1986, and he could be an intimidating presence for lawyers who had to argue there. He had a deep effect on the law and legal thinking through his Supreme Court opinions and speeches. His sharply worded dissents and caustic attacks on liberal notions were quoted widely, and they had an influence on a generation of young conservatives.

1/13

Antonin Scalia, left, with wife Maureen, takes his Supreme Court oath from retiring Chief Justice Warren E. Burger in September 1986.

(Charles Tasnadi / Associated Press) 2/13

President Reagan announced the Supreme Court nomination of Antonin Scalia, left, in June 1986, after Chief Justice Warren E. Burger decided to retire. At right is Justice William Rehnquist, who became chief justice later that year.

(Ron Edmonds / Associated Press) 3/13

In this Aug. 6, 1986 file photo, Supreme Court Justice nominee Antonin Scalia attends a Senate Judiciary Committee during his confirmation hearings in Washington.

(Lana Harris / AP) 4/13

U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Antonin Scalia addresses a Northern Virginia Technology Council (NVTC) breakfast December 13, 2006 in McLean, Virginia.

(Alex Wong / Getty Images) 5/13

Supreme Court Associate Justice Stephen Breyer (L) and fellow Associate Justice Antonin Scalia testifiy before the House Judiciary Committee’s Commercial and Administrative Law Subcommittee on Capitol Hill May 20, 2010 in Washington, DC. Breyer and Scalia testified to the subcommittee about the Administrative Conference of the United States.

(Chip Somodevilla / Getty Images) 6/13

Supreme Court Justices Stephen Breyer (R) and Antonin Scalia (3rd L), escorted by Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-VT) (L), and Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-IA) (2nd L), arrive at a hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee October 5, 2011 on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC. The justices testified on “Considering the Role of Judges Under the Constitution of the United States.”

(Alex Wong / Getty Images) 7/13

Surrounded by security, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia walks October 10, 2005 in the annual Columbus Day Parade in New York City. This is the 61st Columbus Parade which celebrates both the explorer and Italian cultural influence on America.

(Spencer Platt / Getty Images) 8/13

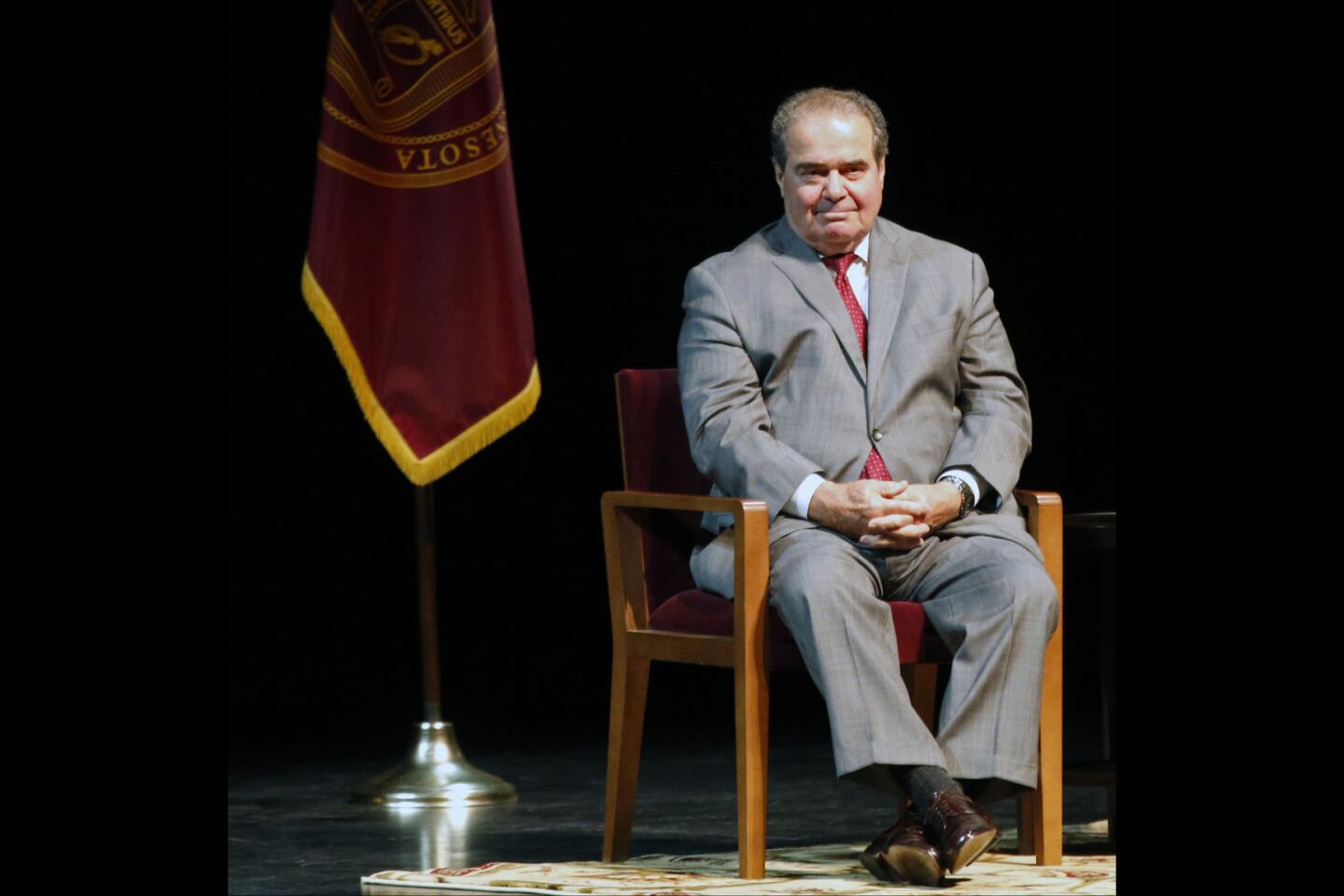

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia waits during an introduction before speaking at the University of Minnesota as part of the law school’s Stein Lecture series, Tuesday, Oct. 20, 2015, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/Jim Mone)

(Jim Mone / AP) 9/13

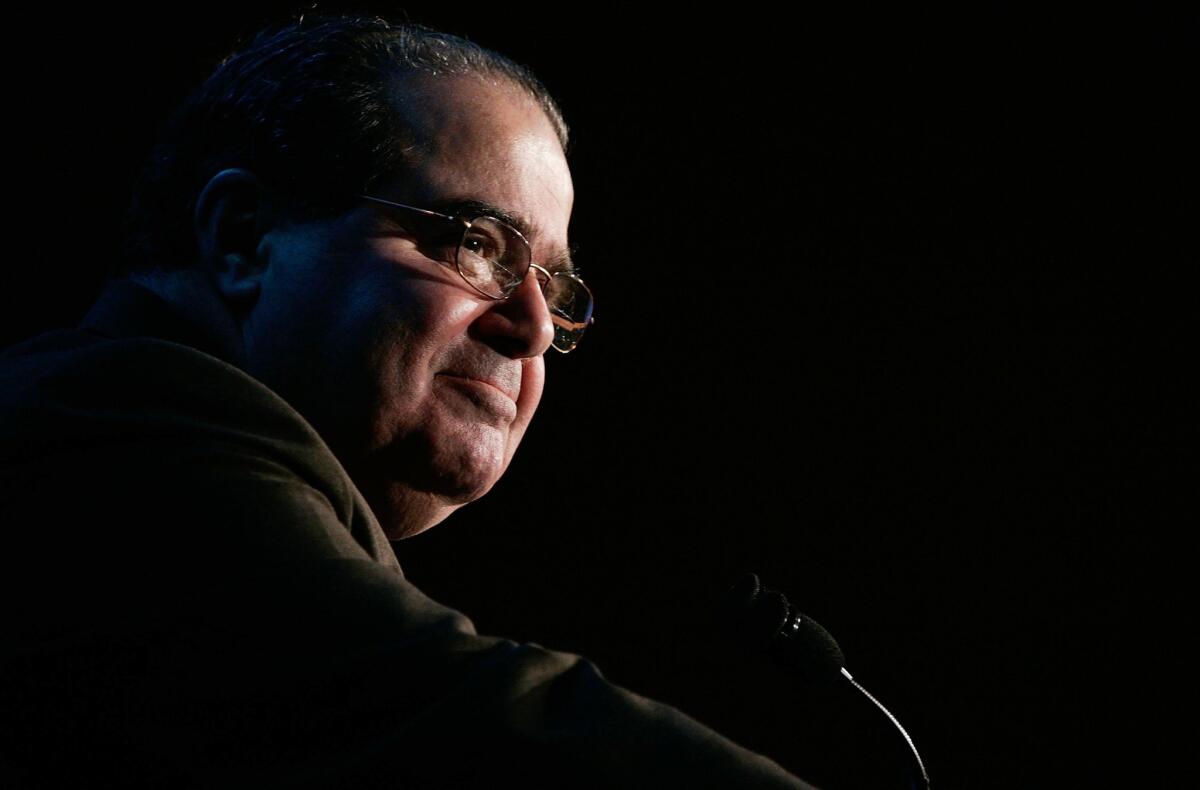

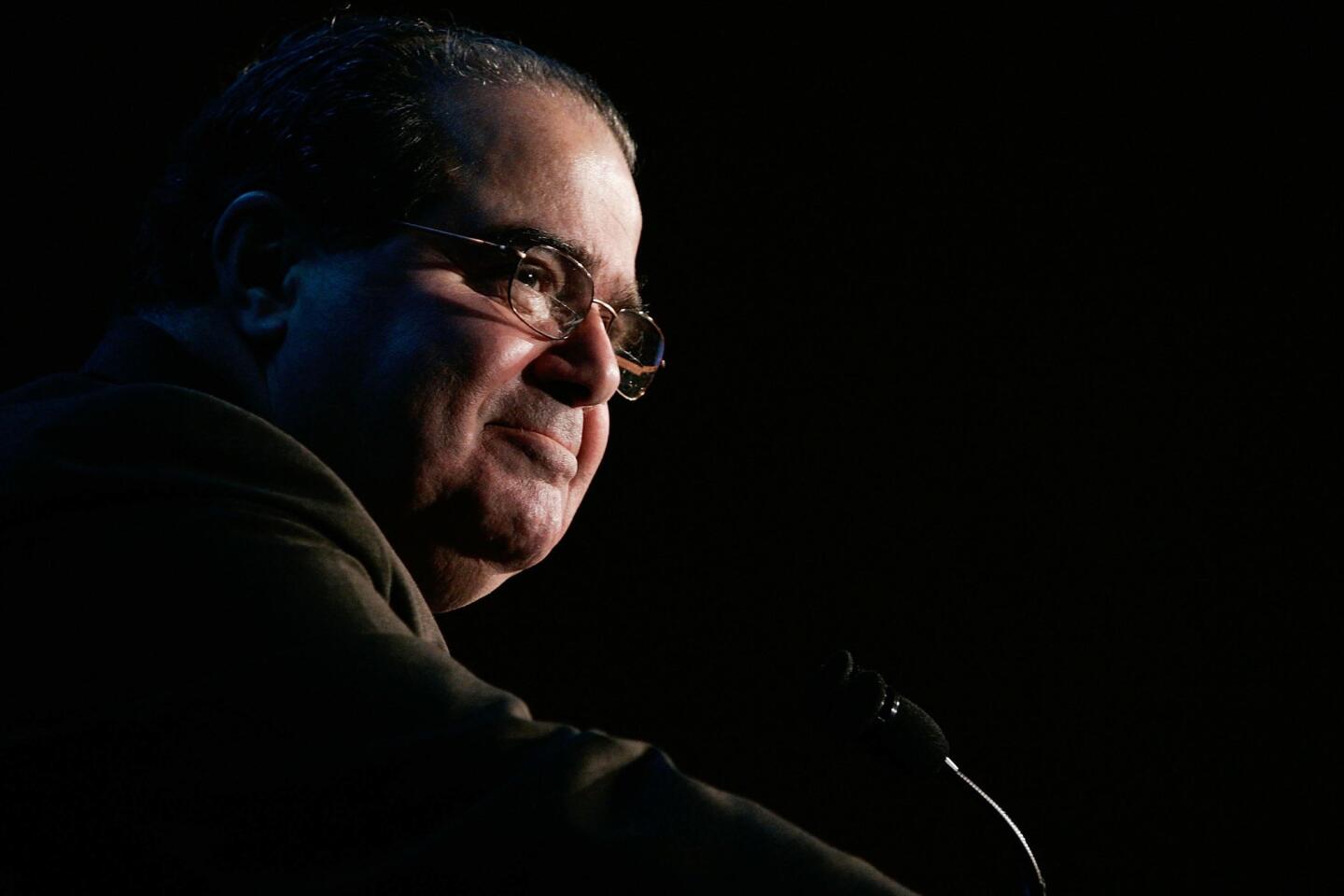

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia during a speech on Feb. 10, 2004, at Amherst College in Amherst, Mass.

(DENNIS VANDAL / AP) 10/13

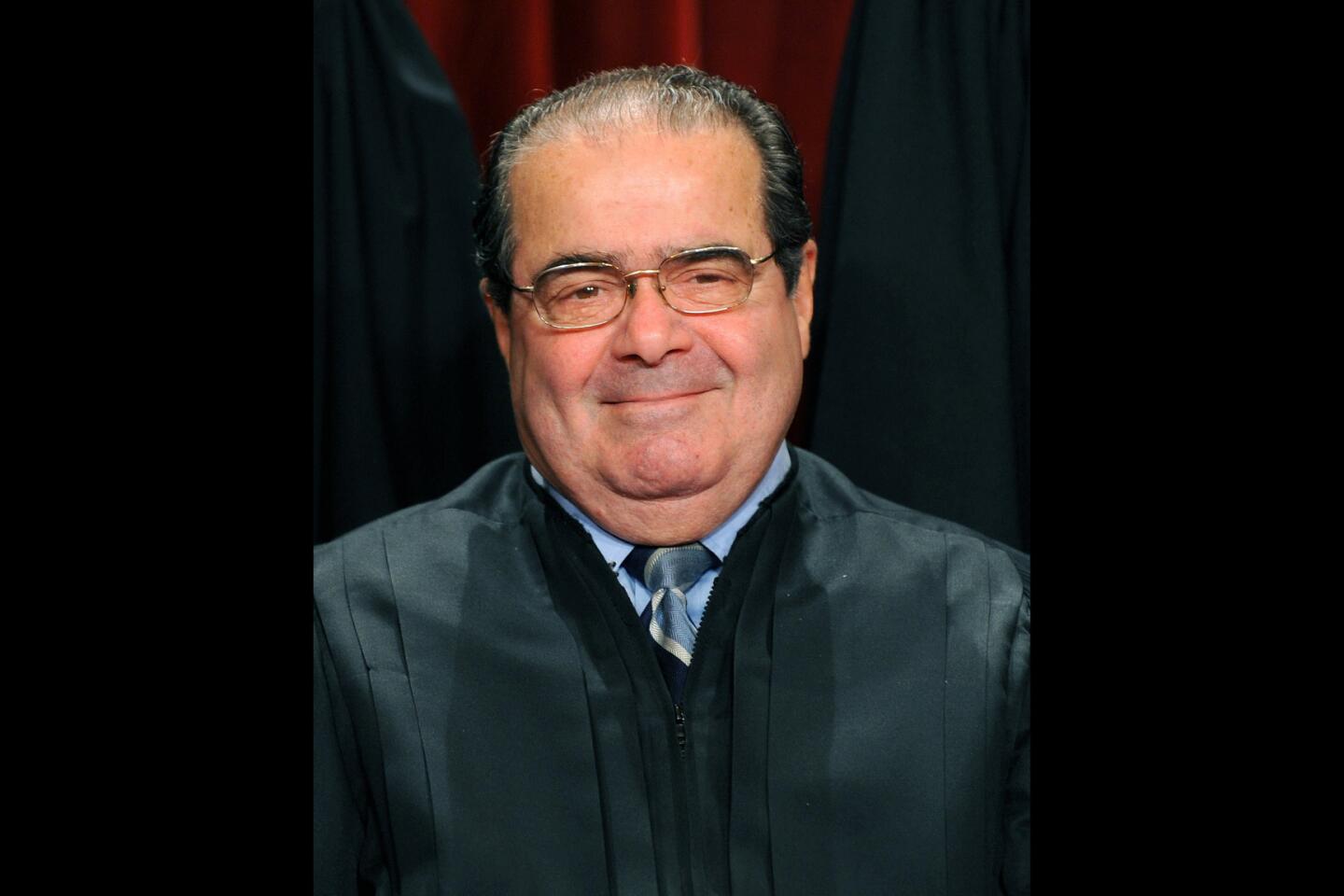

US Supreme Court Associate Justice Antonin Scalia in the court’s official photo session on Oct. 8, 2010.

(TIM SLOAN / AFP/Getty Images) 11/13

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia speaks at the Economics Club of New York in February 2016.

(PETER FOLEY / EPA) 12/13

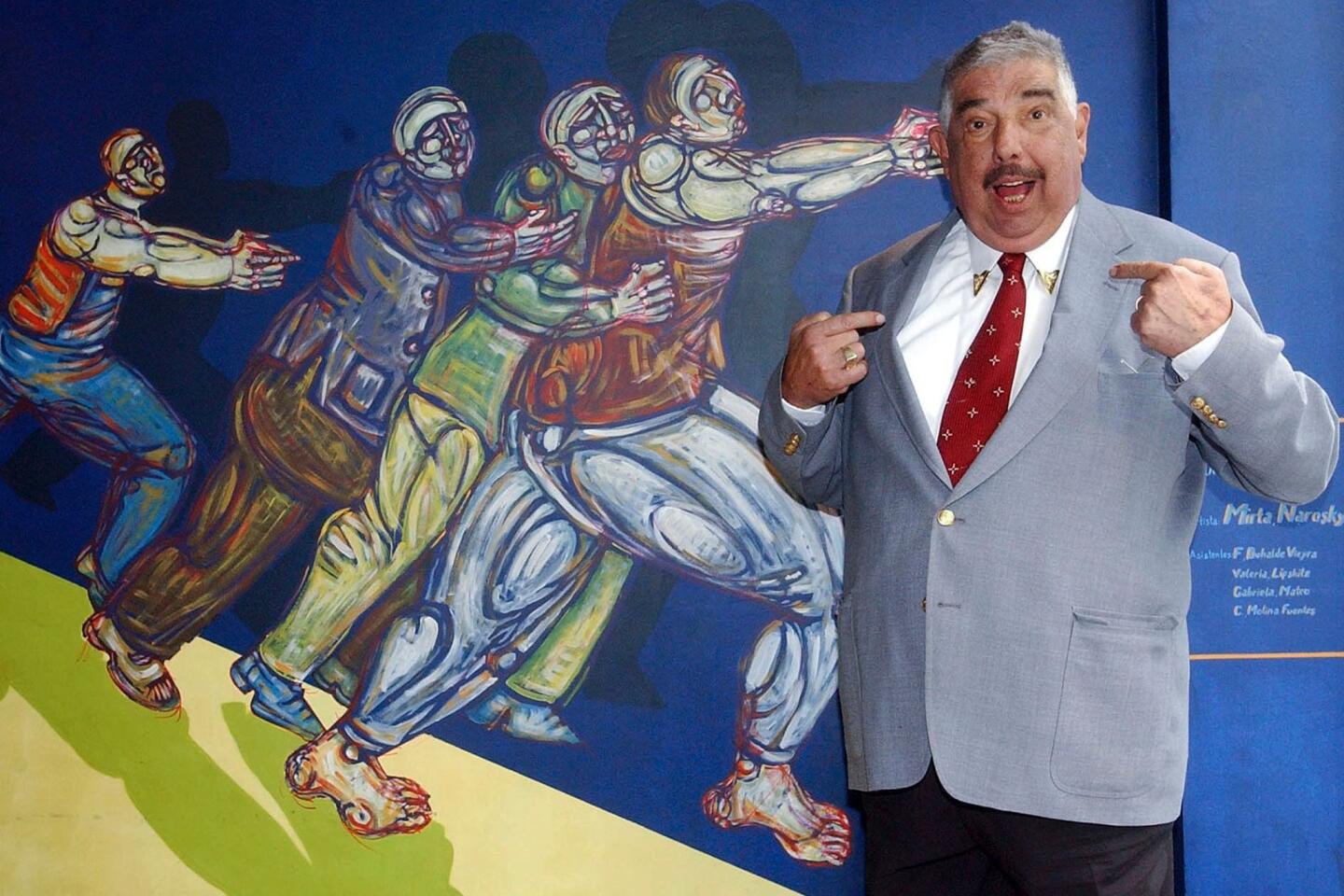

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, playing the role of Chief Justice Melville Weston Fuller, talks to California Atty. Gen. Bill Lockyer, representing part of the counsel for the state of New York, during a re-enactment of the 100-year-old case of Lochner vs New York on Monday, Aug. 29, 2005, at Chapman University in Orange.

(SANG H. PARK / AP) 13/13

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia after addressing an assembly in front of LSU’s Paul M. Hebert Law Center in Baton Rouge, La., on Oct. 24, 2003.

(BILL HABER / AP) But inside the court, his rigid style of conservatism and derisive jabs directed at his colleagues limited his effectiveness. Scalia himself seemed to relish the role of the angry dissenter.

As a justice, he was the leading advocate for interpreting the Constitution by its original words and meaning, and not in line with contemporary thinking. He said he liked a “dead Constitution,” not a “living” one that evolves with the times.

Reaction from political leaders reflected Scalia’s firm commitment to this philosophy.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) lauded Scalia as “a giant of American jurisprudence” who “almost singlehandedly revived an approach to constitutional interpretation that prioritized the text and original meaning of the Constitution.”

Sen. Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) praised the justice as “a brilliant man with a probing mind,” while acknowledging that he “disagreed with him on so many issues.”

Donald Trump, the real estate magnate and reality TV star turned Republican presidential candidate, said Scalia’s “career was defined by his reverence for the Constitution and his legacy of protecting Americans’ most cherished freedoms.”

Former President George W. Bush called Scalia “a towering figure” who “brought intellect, good judgment, and wit to the bench.”

In Scalia’s view, laws can change when voters call for changes, but the Constitution itself should not change through the rulings of judges.

As Scalia saw it, the difficult constitutional questions of recent decades were easy to resolve if viewed through the prism of the late 18th century when the Constitution was written.

“The death penalty? Give me a break. It’s easy. Abortion? Absolutely easy. Nobody ever thought the Constitution prevented restrictions on abortion. Homosexual sodomy? Come on. For 200 years, it was criminal in every state,” Scalia told the American Enterprise Institute in 2012.

If such comments made him sound old, grumpy and out of touch with modern America, Scalia would agree—and see it as a compliment. He said his job was to preserve an “enduring” Constitution.

He also had a comic’s sense of timing. Several law professors studied the transcripts of the court’s oral arguments and confirmed what a court observer would see every day. Scalia’s sarcastic questions and his cut-to-the point comments provoked laughter in the courtroom far more often than any of his colleagues.

In October 2011, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., a former lawyer before the court, marked the 25th anniversary of Scalia’s arrival by saying “the place hasn’t been the same since.”

Before Scalia ascended to the high court in 1986, most of its justices shared the view that the Constitution was a progressive document which promised justice and equality for all. They had interpreted it in the 1960s and 1970s as giving women equal rights -- including a right to abortion -- as forbidding official prayers in public schools, as requiring police to warn criminal suspects of their rights, and for a time, blocking the death penalty as cruel and unusual punishment.

Scalia thought none of these decisions was correct. He said these rulings reflected liberal politics more than a faithful reading of the original Constitution. And he voiced his critique year after year, sometimes in angry dissents and sometimes in sarcastic comments directed at his liberal colleagues.

His tone was mournful at times. “Day by day, case by case, [the court] is designing a Constitution for a country that I do not recognize,” he wrote in a 1996 dissent.

He issued thunderous dissents when the court upheld the right to abortion in 1992 and in 2003 when it struck down the sex laws that targeted gays and lesbians. Then, he accused his colleagues of having “largely signed on to the so-called homosexual agenda … directed at eliminating the moral opprobrium that has traditionally attached to homosexual conduct.”

He predicted the ruling would trigger a national debate over same-sex marriage, and he was proved correct. A few months later, the Massachusetts high court became the first to rule that gays and lesbians had an equal right to marry. A decade later, a majority of Americans agreed gays deserved the right to marry.

During his first two decades on the court, Scalia was known mostly for his dissents. He broke with fellow Reagan appointees—Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and Anthony Kennedy—because they refused to overturn the court’s precedents on abortion, school prayer and the Miranda warnings to criminal defendants about their legal rights.

But after Chief Justice William Rehnquist died in 2005 and O’Connor retired a few months later, Scalia took on a new prominence as a leader of the court’s conservative wing. Roberts, the new chief justice who was a generation younger than Scalia, deferred to him and often assigned him to write the court’s opinion in momentous cases.

In what may have been his most important majority opinion, Scalia spoke for the court in 2008 declaring for the first time that the 2nd Amendment gave Americans a right to own a gun for self-defense. A lifelong hunter, Scalia said the “right to bear arms” had been understood as a fundamental right since the American colonies became independent.

Scalia also played a key role in a series of 5-4 decisions that struck down campaign finance laws and said that all Americans—including corporations and unions—had a free-speech right to spend their money on election ads.

Scalia was an old-school traditionalist. He was fiercely determined to fight a rear-guard battle against modern trends. A Catholic, he and his wife Maureen had nine children, and he insisted they go each Sunday to a church with a traditional Latin Mass. On Saturdays, however, Scalia liked nothing better than hiding in a duck blind waiting for unwary birds to fly overhead.

1/61

Wong’s masterly touch brought a poetic quality to Disney’s “Bambi” that has helped it endure as a classic of animation. The pioneering Chinese American artist influenced later generations of animators. Full obituary

(Peter Brenner / Handout) 2/61

After bursting onto the scene opposite Gene Kelly in the classic 1952 musical “Singin’ in the Rain,” Reynolds became America’s Sweetheart and a potent box office star for years. Her passing came only one day after her daughter, Carrie Fisher, died at the age of 60. Reynolds was 84. Full obituary

(John Rooney / Associated Press) 3/61

George Michael, the English singer-songwriter who shot to stardom in the 1980s as half of the pop duo Wham!, went on to become one of the era’s biggest pop solo artists with hits such as “Faith” and “I Want Your Sex.” He was 53. Full obituary

(Francois Mori / Associated Press) 4/61

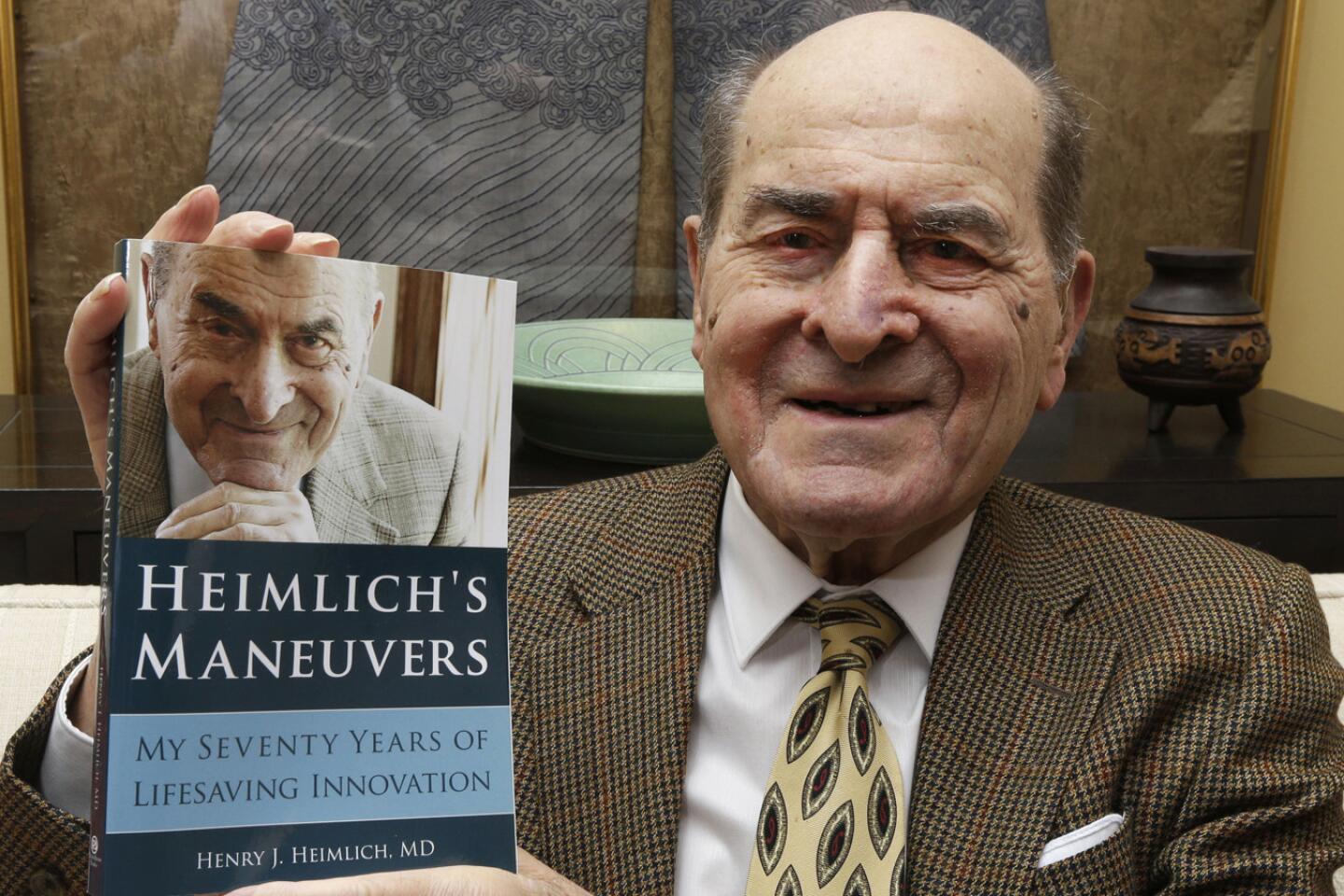

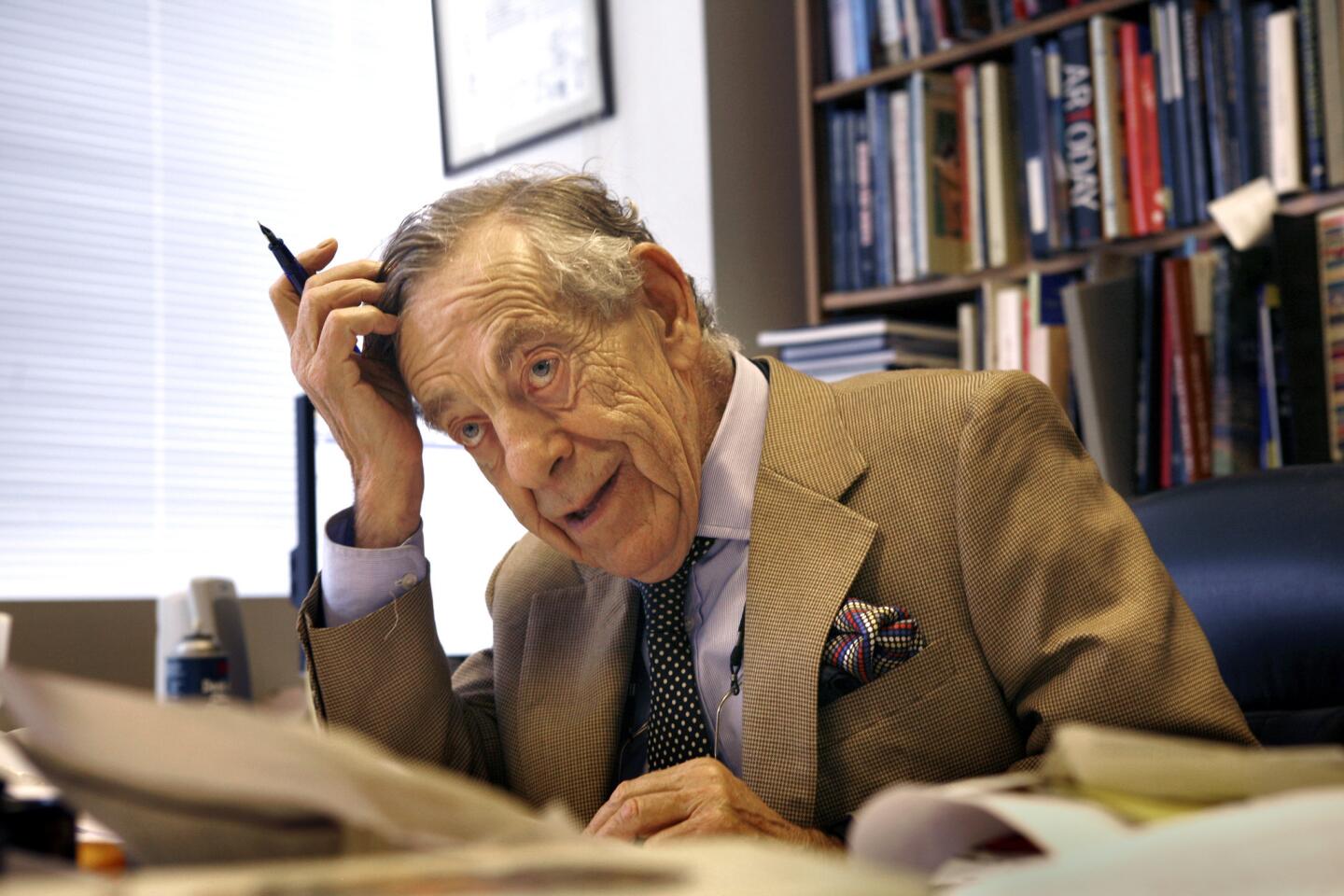

The thoracic surgeon came up with an anti-choking technique in 1974. So simple it could be performed by children, the eponymous maneuver made Heimlich a household name. He was 96. Full obituary

(Al Behrman / Associated Press) 5/61

The hugely popular south Indian actress later turned to politics and became the highest elected official in the state of Tamil Nadu. She was 68. Full obituary

(AFP / Getty Images) 6/61

Best known for her portrayal of Carol Brady on “The Brady Bunch,” Henderson

portrayed an idealized mother figure for an entire generation. Her character was the center of the show, cheerfully mothering her brood in an era when divorce was becoming more common. She was 82. Full obituary

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 7/61

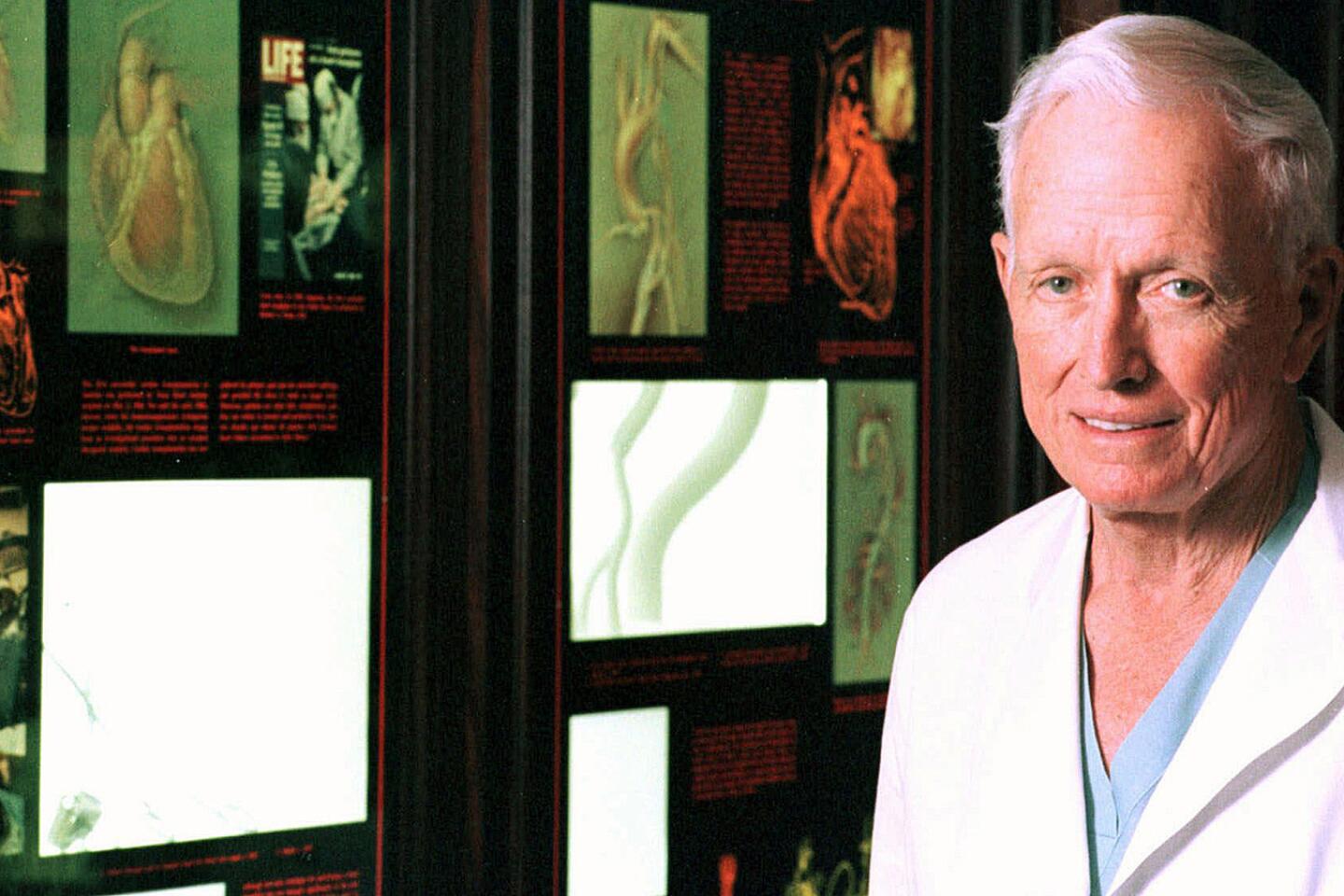

Dubbed “Dr. Wonderful” by the media, the Texas surgeon performed the first successful heart transplant in the United States and the world’s first implantation of a wholly artificial heart. He also founded the Texas Heart Institute in Houston. He was 96. Full obituary

(David J. Phillip / Associated Press) 8/61

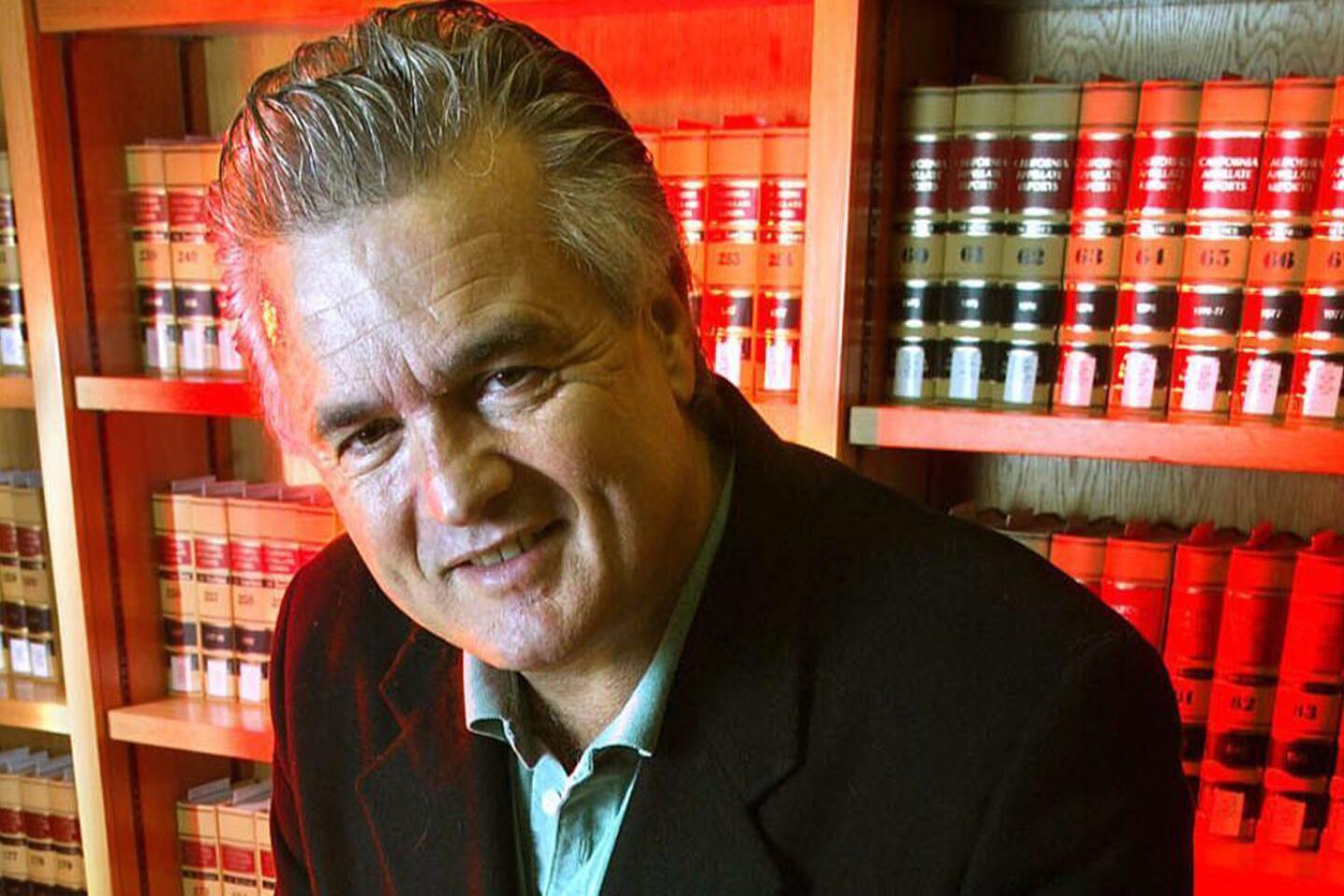

The prominent Los Angeles attorney went from defending his father, a powerful mob boss, to representing celebrities, corrupt businessmen, drug kingpins and the so-called Hollywood Madam, Heidi Fleiss. He was 70. Full obituary

(Ken Hively / Los Angeles Times) 9/61

The award-winning journalist wrote for the Washington Post and the New York Times before becoming an anchor of public television news programs “PBS NewsHour” and “Washington Week.” Her career also included moderating the vice presidential debates in 2004 and 2008. She was 61. Full obituary

(Brendan Smialowski / Getty Images) 10/61

Instantly recognizable for his long white mane and a rich, hearty voice, Russell sang, wrote and produced some of rock ‘n’ roll’s top records. His hits included “Delta Lady,” “Roll Away the Stone,” “A Song for You” and “Superstar.” He was 74. Full obituary

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 11/61

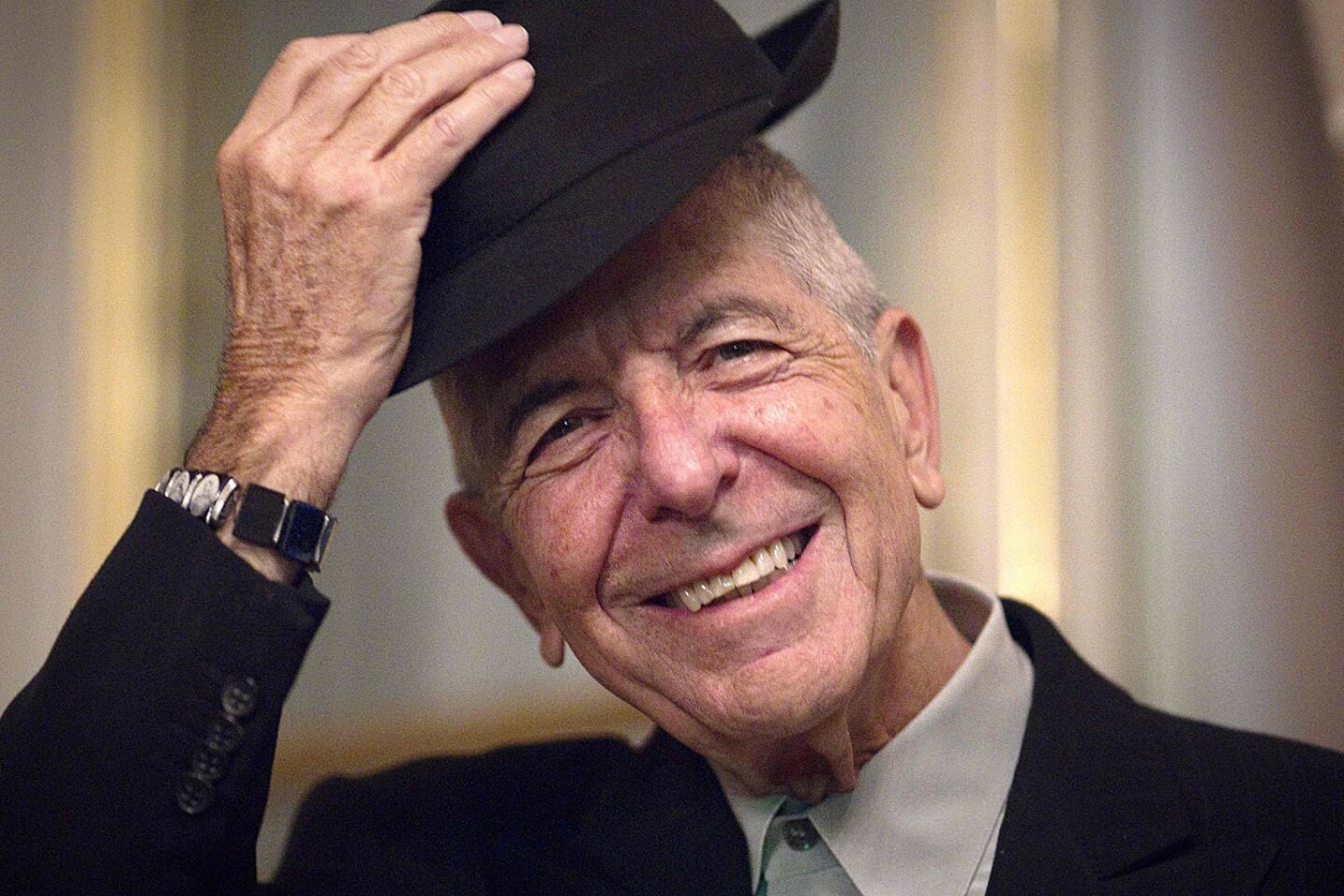

The singer-songwriter’s literary sensibility and elegant dissections of desire made him one of popular music’s most influential and admired figures for four decades. Cohen is best known for his songs such as “Hallelujah,” “Suzanne” and “Bird on the Wire.” He was 82. Full obituary

(Joel Saget / AFP / Getty Images) 12/61

Reno was the first woman to serve as United States attorney general. Her unusually long tenure began with a disastrous assault on cultists in Texas and ended after the dramatic raid that returned Elian Gonzalez to his Cuban father. She was 78. Full obituary

(Dennis Cook / Associated Press) 13/61

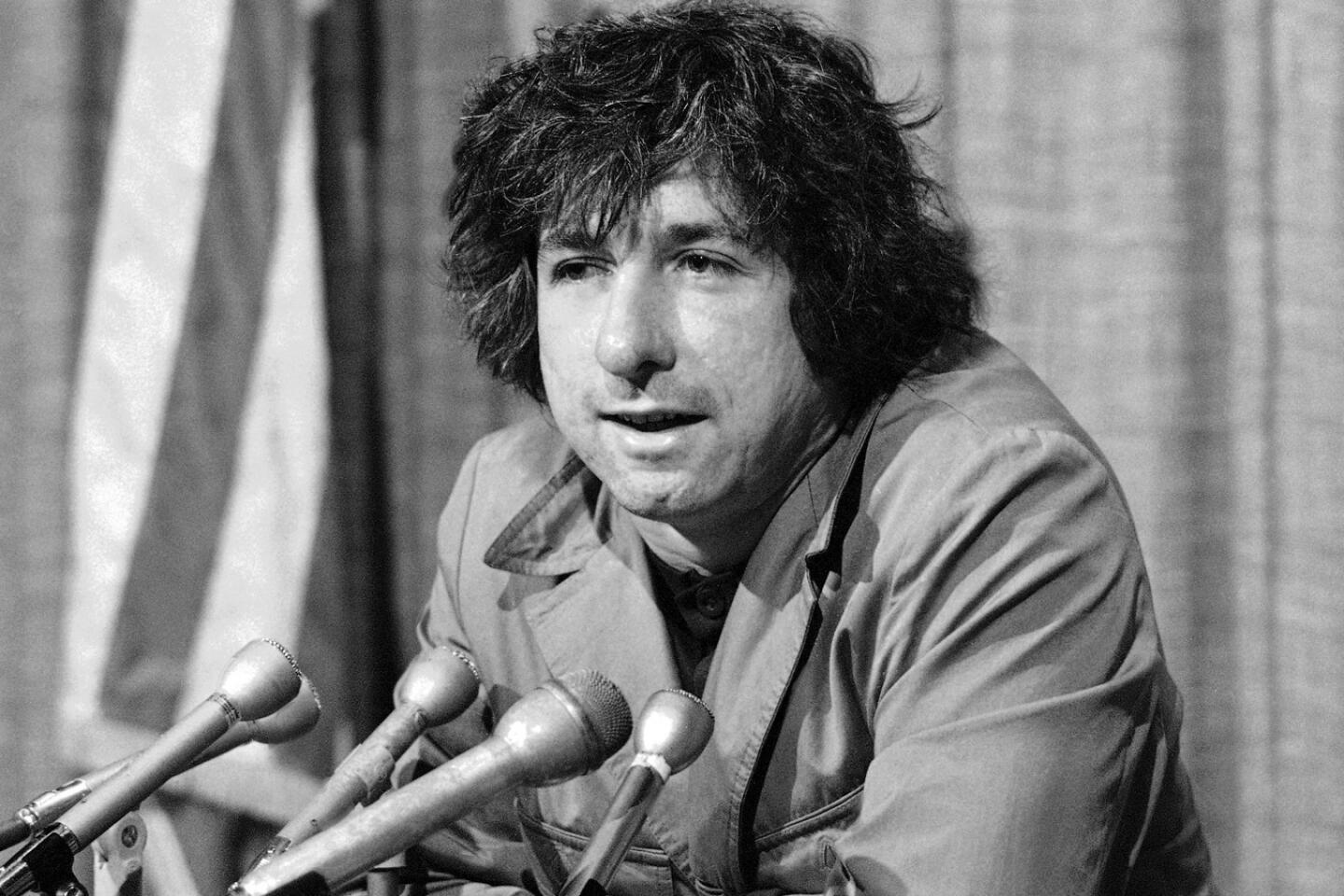

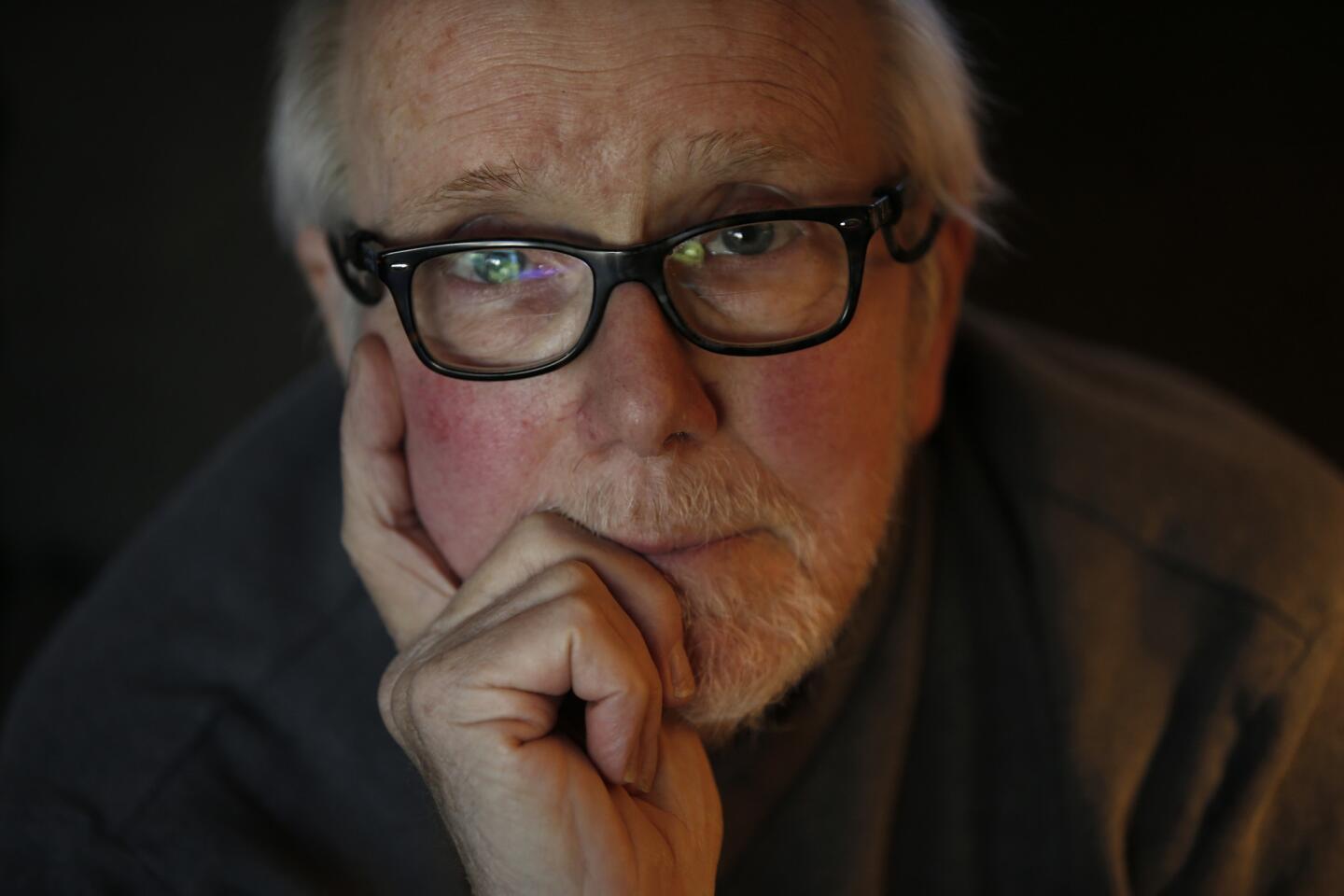

The 1960s radical was in the vanguard of the movement to stop the Vietnam War and became one of the nation’s best-known champions of liberal causes. He was 76. Full obituary

(George Brich / Associated Press) 14/61

Tabei was the first woman to climb Mount Everest in 1975. In 1992, she also became the first woman to complete the “Seven Summits,” reaching the highest peaks of the seven continents. She was 77. Full obituary

(AFP / Getty Images) 15/61

Nixon was the creative force behind the popular soap operas “One Life to Live” and “All My Children.” She was a pioneer in bringing serious social issues, like racism, AIDS and prostitution, to daytime television. She was 93. Full obituary

(Chris Pizzello / Associated Press) 16/61

The former Israeli president was one of the founding fathers of Israel. The Nobel peace prize laureate was an early advocate of the idea that Israel’s survival depended on territorial compromise with the Palestinians. He was 93. Full obituary

(AFP / Getty Images) 17/61

A seven-time professional major tournament champion, Palmer revolutionized sports marketing as it is known today, and his success contributed to increased incomes for athletes across the sporting spectrum. He was 87. Full obituary

(David J. Phillip / Associated Press) 18/61

Known as the Vatican’s exorcist, Amorth, a Roman Catholic priest, helped promote the ritual of banishing the devil from people or places. He was 91. Full obituary

(AFP / Getty Images) 19/61

The American playwright was known for works such as “The Zoo Story,” “The Sandbox,” “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” and “A Delicate Balance.” He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for drama three times. He was 88. Full obituary

(Jennifer S. Altman / For the Times) 20/61

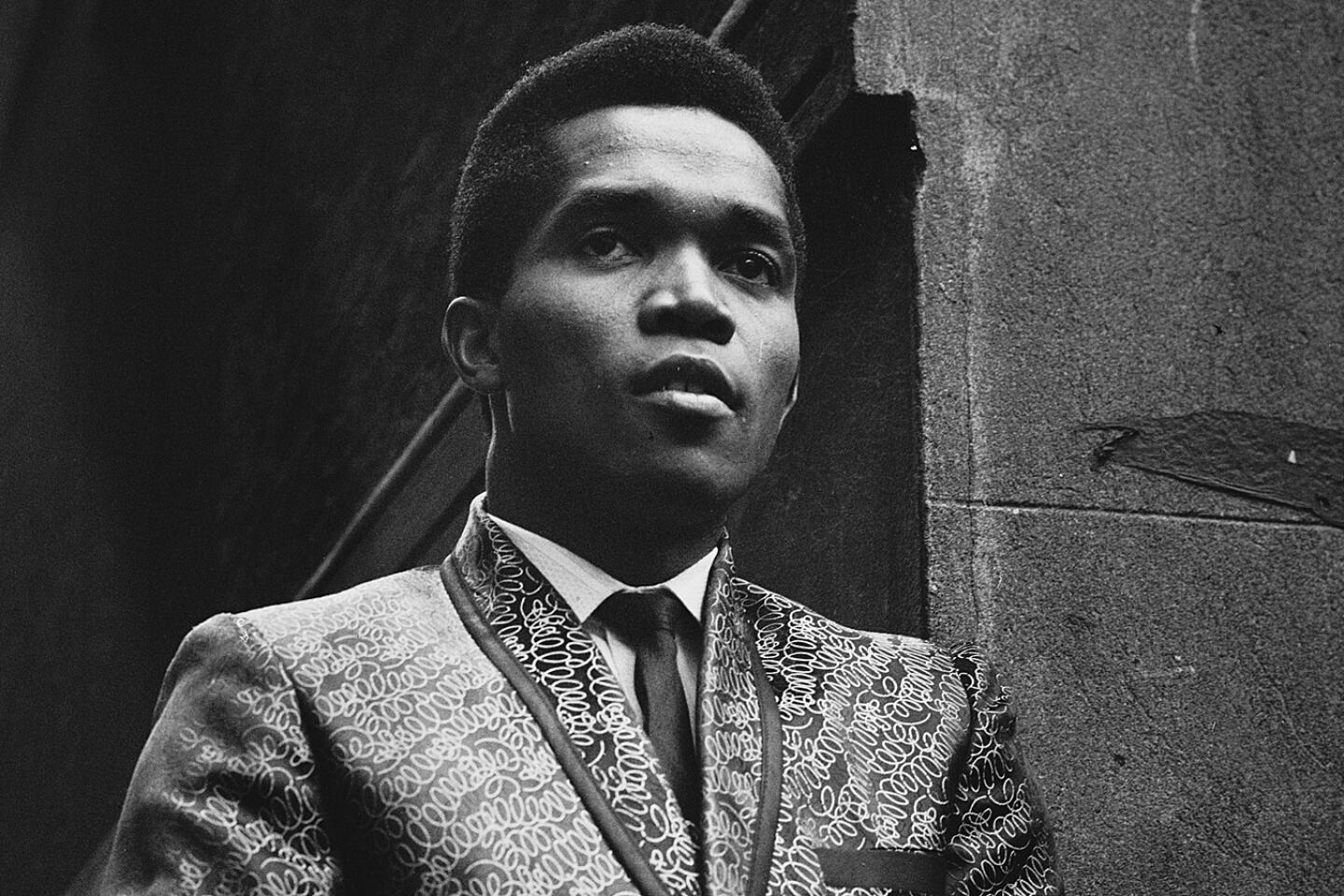

The ska pioneer and Jamaican music legend recorded thousands of records, including such hits as “Al Capone” and “Judge Dread.” He helped ignite the ska movement in England, and later helped carry it into the rock-steady era in the mid-1960s. He was 78. Full obituary

(Larry Ellis / Getty Images) 21/61

Known as “the first lady of anti-feminism,” Schlafly was a political activist who galvanized grass-roots conservatives to help defeat the Equal Rights Amendment and, in ensuing decades, effectively push the Republican Party to the right. She was 92. Full obituary

(Christine Cotter / Los Angeles Times) 22/61

O’Brian helped tame the Wild West as the star of TV’s “The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp” and was the founder of a long-running youth leadership development organization. “Wyatt Earp” became a top 10-rated series and made O’Brian a household name. He was 91. Full obituary

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times) 23/61

Jerry Heller, the early manager of N.W.A, was an important and colorful personality in the emerging West Coast rap scene in the 1980s. Heller was 75. Full obituary

(Lori Shepler / Los Angeles Times) 24/61

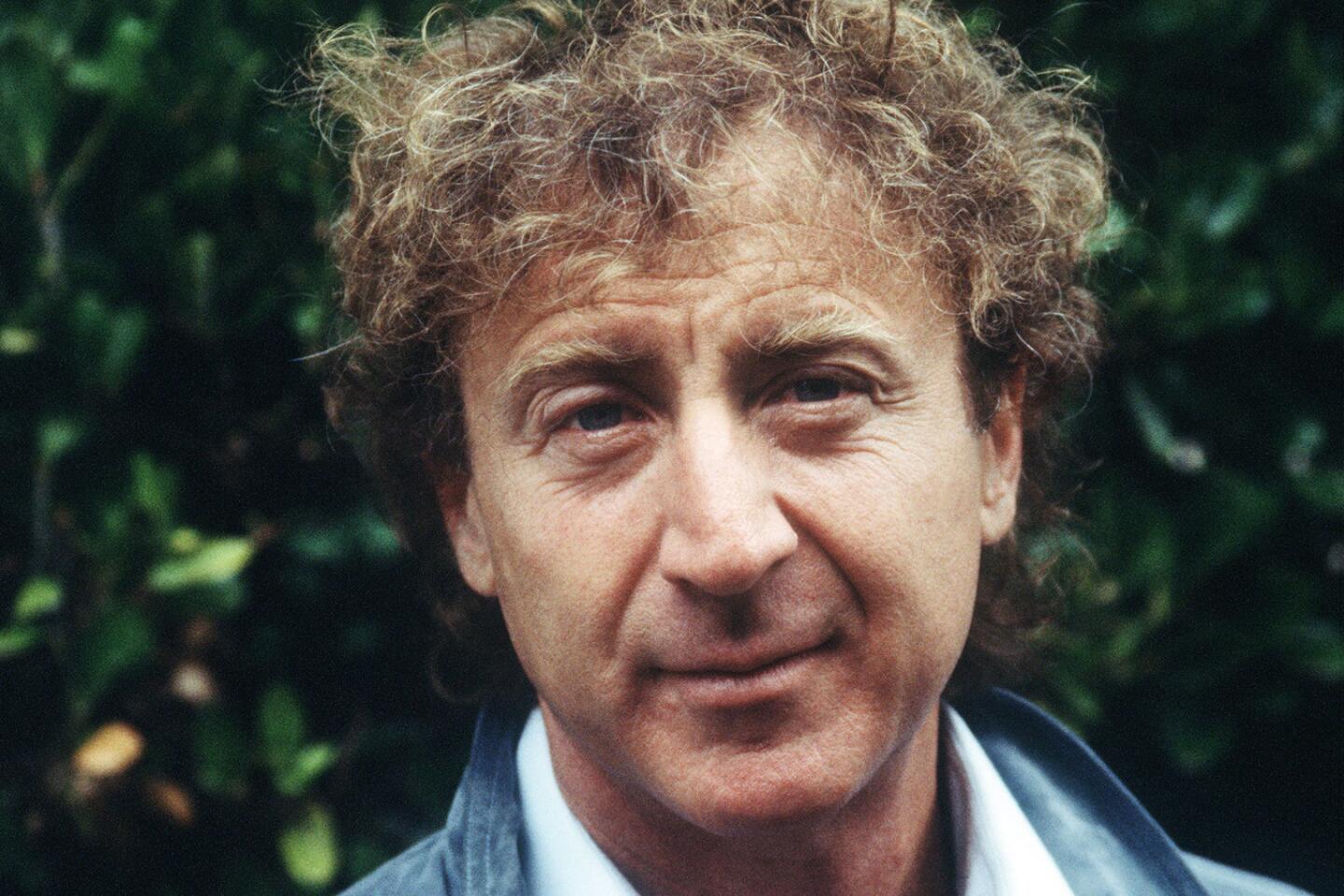

Two-time Oscar nominee Gene Wilder brought a unique blend of manic energy and world-weary melancholy to films as varied as 1971’s children’s movie “Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory” and the 1980 comedy “Stir Crazy.” He was 83. Full obituary

(AFP / Getty Images) 25/61

The beloved top-selling Mexican singer wooed crowds on both sides of the border with ballads of love and heartbreak for more than four decades. He was 66. Full obituary

(Wilfredo Lee / Associated Press) 26/61

Known as the “queen of knitwear,” Sonia Rykiel became a fixture of Paris’ fashion scene, starting in 1968. French President Francois Hollande praised her as “a pioneer” who “offered women freedom of movement.” She was 86. Full obituary

(Thibault Camus / Associated Press) 27/61

The conservative political commentator hosted the long-running weekly public television show “The McLaughlin Group” that helped alter the shape of political discourse since its debut in 1982. He was 89. Full obituary

(Kevin Wolf / Associated Press) 28/61

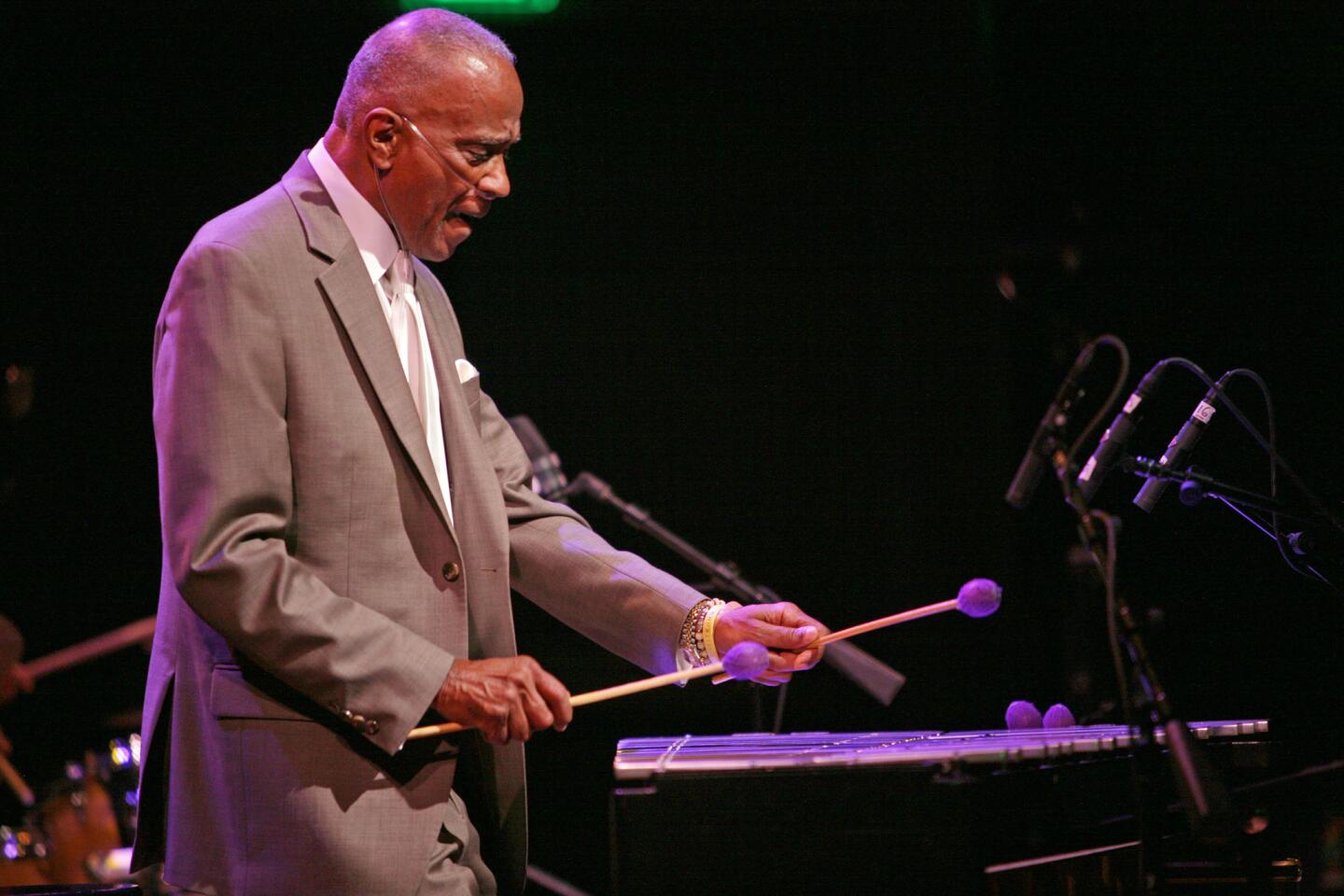

Best-known for his post-bop recordings for Blue Note Records in the 1960s and 1970s, the inventive jazz vibraphonist played with a litany of jazz greats as both bandleader and sideman during a career spanning more than 50 years. He was 75. Full obituary

(Scott Chernis / Associated Press) 29/61

The British actor, who was 3-foot-8, gave life to the “Star Wars” droid R2-D2, one of the most beloved characters in the space-opera franchise and among the most iconic robots in pop culture history. He was 81. Full obituary

(Reed Saxon / Associated Press) 30/61

For many in L.A., Folsom was the face of the Parent Teacher Student Assn., better known as the PTSA or PTA. He served as the official and unofficial watchdog over the Los Angeles Unified School District and wrote about his experiences in his blog. He was 69. Full obituary

(Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times) 31/61

Fountain combined the Swing Era sensibility of jazz clarinetist Benny Goodman with the down-home, freewheeling style characteristic of traditional New Orleans jazz to become a national star in the 1950s as a featured soloist on the “The Lawrence Welk Show.” He was 86. Full obituary

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 32/61

Lowery was a pioneer in efforts to help people suffering from poverty, addiction and mental illness move out of tents and cardboard boxes on Los Angeles’ sidewalks and into supportive housing. She was 70. Full obituary

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 33/61

Nixon, a Hollywood voice double, can be heard in place of the leading actresses in such classic movie musicals as “West Side Story,” “The King and I” and “My Fair Lady.” She was 86. Full obituary

(Rob Kim / AFP/Getty Images) 34/61

The department store heir’s widow was a socialite and philanthropist who hobnobbed with the world’s elite, epitomized high fashion and was best friends with former first lady Nancy Reagan. She was 93. Full obituary

(Evan Agostini / Associated Press) 35/61

The author and teacher was long established as a leading literary figure of Southern California. Her works include “Golden Days,” “There Will Never Be Another You” and her memoir “Dreaming, Hard Luck and Good Times in America.” She was 82. Full obituary

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times) 36/61

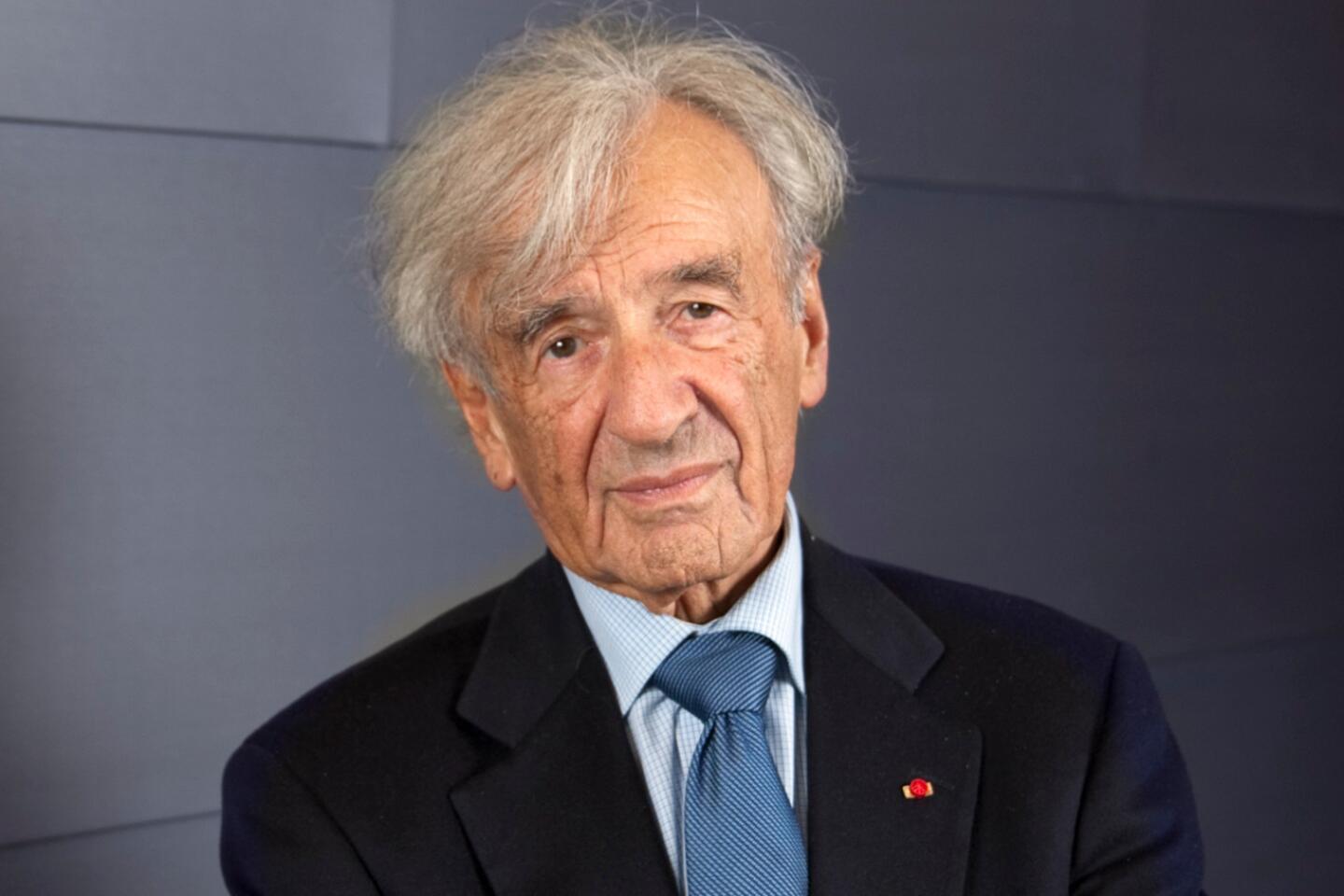

The Nazi concentration camp survivor won the Nobel in 1986 for his message “of peace, atonement and human dignity.” “Night,” his account of his year in death camps, is regarded as one of the most powerful achievements in Holocaust literature. He was 87. Full obituary

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 37/61

One of the greatest basketball coaches of any gender or generation, Summitt spent 38 years as coach of the University of Tennessee women’s basketball team before dementia forced her early retirement. She was 64. Full obituary

(Wade Payne / Associated Press) 38/61

The iconic New York Times fashion photographer darted around New York on a humble bicycle to cover the style of high society grand dames and downtown punks with equal verve. He was 87. Full obituary

(Mark Lennihan / Associated Press) 39/61

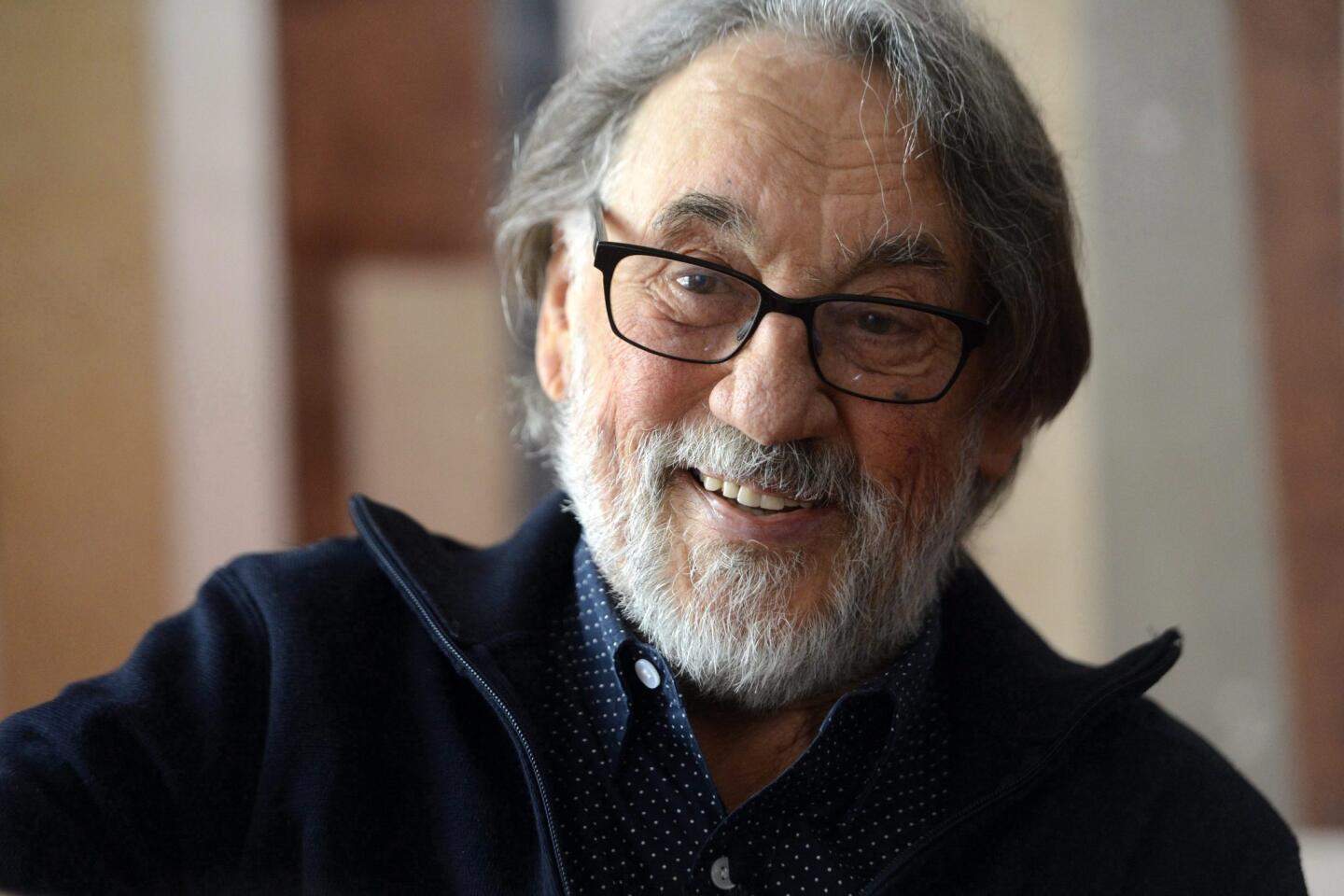

Aguirre was best known for his portrayal of the towering “Profesor Jirafales,” the likable and often disrespected giraffe teacher on the 1970s-era hit show “El Chavo del Ocho.” The screwball comedy helped usher in an era of edgier comedy in Mexico and elsewhere. Aguirre was 82. Full obituary

(AFP / Getty Images) 40/61

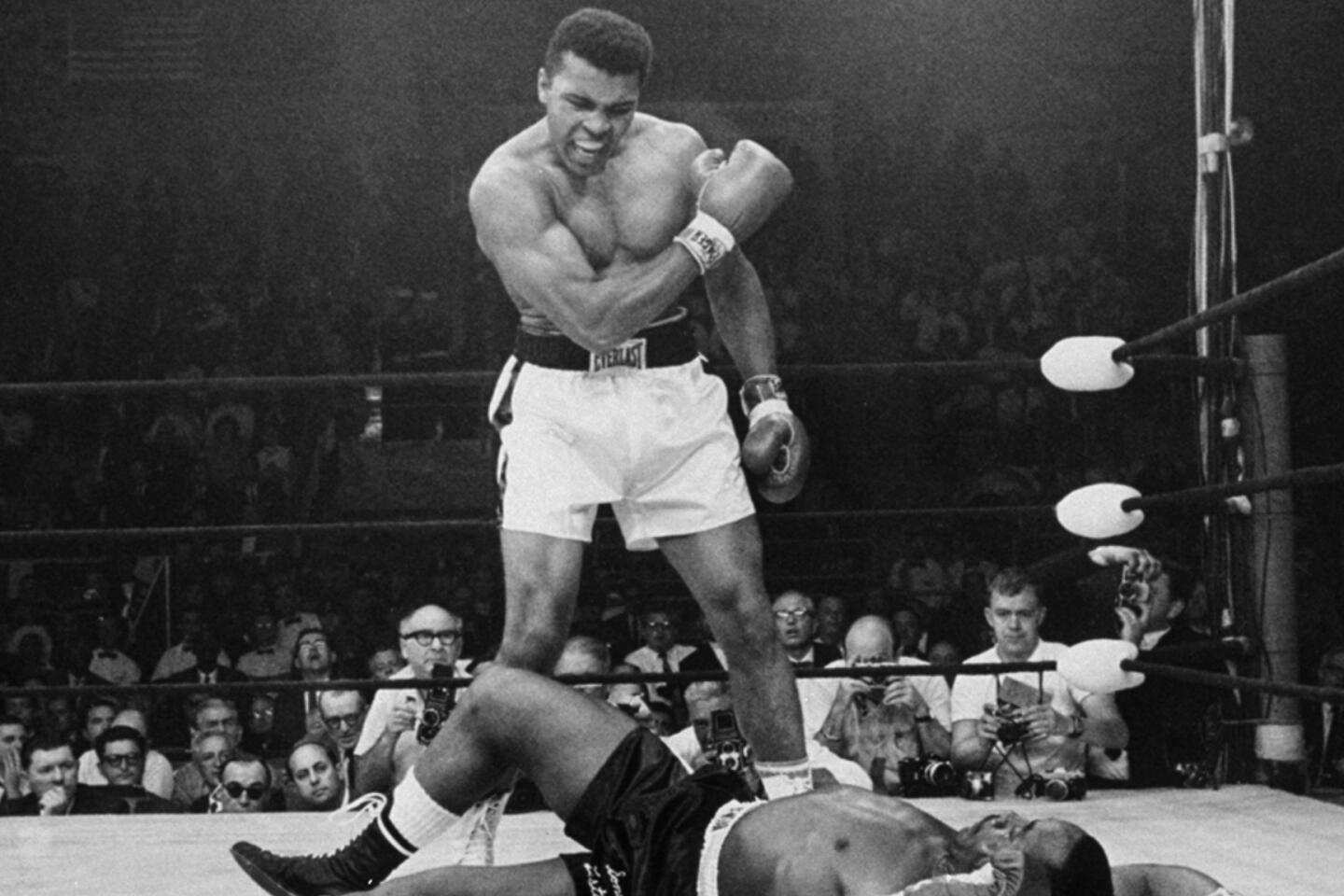

The three-time heavyweight boxing champion’s brilliance in the ring and bravado outside it made his face one of the most recognizable in the world. He was 74. Full obituary

(John Rooney / Associated Press) 41/61

Like Walter Cronkite and Edward R. Murrow, the CBS newsman became part of a group of journalists who set the tone for storytelling on television. He was on “60 Minutes” for 46 years, holding the longest tenure on prime-time television of anyone in history. He was 84. Full obituary

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 42/61

The first African American chief of the Los Angeles Police Department, Williams steadied the agency in the tumultuous wake of the 1992 riots but was distrusted as an outsider by many officers and politicians. He was 72. Full obituary

(Nick Ut / Associated Press) 43/61

Best known for her role as Marie Barone on “Everybody Loves Raymond,” Roberts won four Emmys for her work on that show and one for her work on “St. Elsewhere.” She was 90. Full obituary

(Ken Hively / Los Angeles Times) 44/61

The country music legend sang of his law-breaking Bakersfield youth and penned a stream of No. 1 hits. He owed some of his fame to conservative anthems, including the combative 1969 release “Okie from Muskogee,” which seemed to mock San Francisco’s anti-war hippies. He was 79. Full obituary

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times) 45/61

The acclaimed Native American historian was the last surviving war chief of Montana’s Crow Tribe. President Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009. He was 102. Full obituary

(J. Scott Applewhite / Associated Press) 46/61

Germany’s longest-serving foreign minister brokered an end to the painful 40-year division of his homeland in 1990, but only after persevering for decades through the most tragic and destructive phases of Germany’s 20th century history. He was 89. Full obituary

(Martin Meissner / Associated Press) 47/61

The Iraqi-born British architect was the first woman to win the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s highest honor. She made her mark with buildings such as the London Aquatics Centre, the MAXXI museum for contemporary art in Rome and the innovative Bridge Pavilion in Zaragoza, Spain. She was 65. Full obituary

(Kevork Djansezian / Associated Press) 48/61

The former television talk show host became the first openly gay man to serve on the Los Angeles City Council. He advocated for the homeless, gays and lesbians and other liberal causes. He was 70. Full obituary

(Christina House / For The Times) 49/61

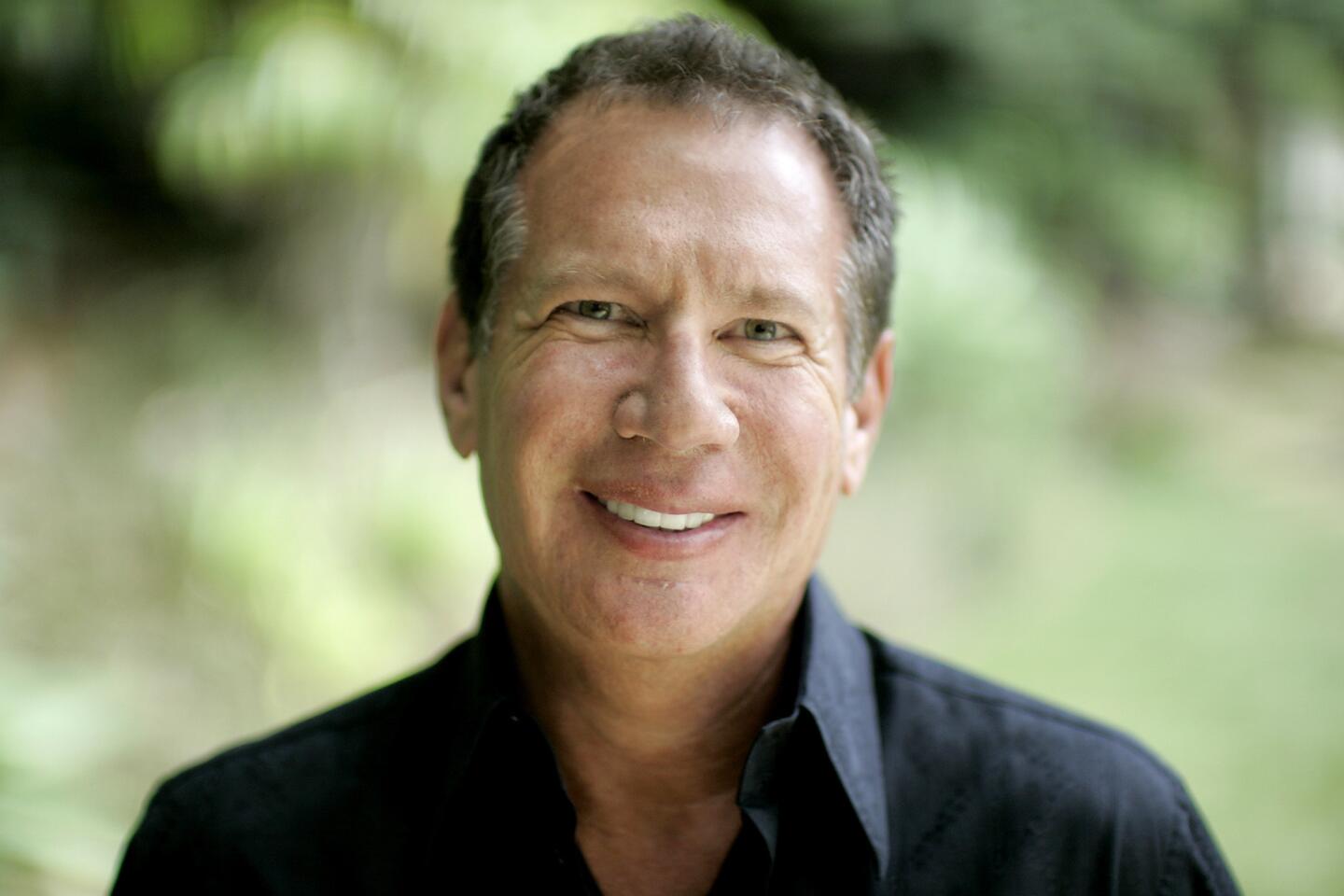

Garry Shandling’s comedic career spanned decades, but he is best known for his role as Larry Sanders, the host of a fictional talk show. His sitcom pushed the boundaries of TV, influencing shows such as “The Office” and “Modern Family.” He was 66. Full obituary.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 50/61

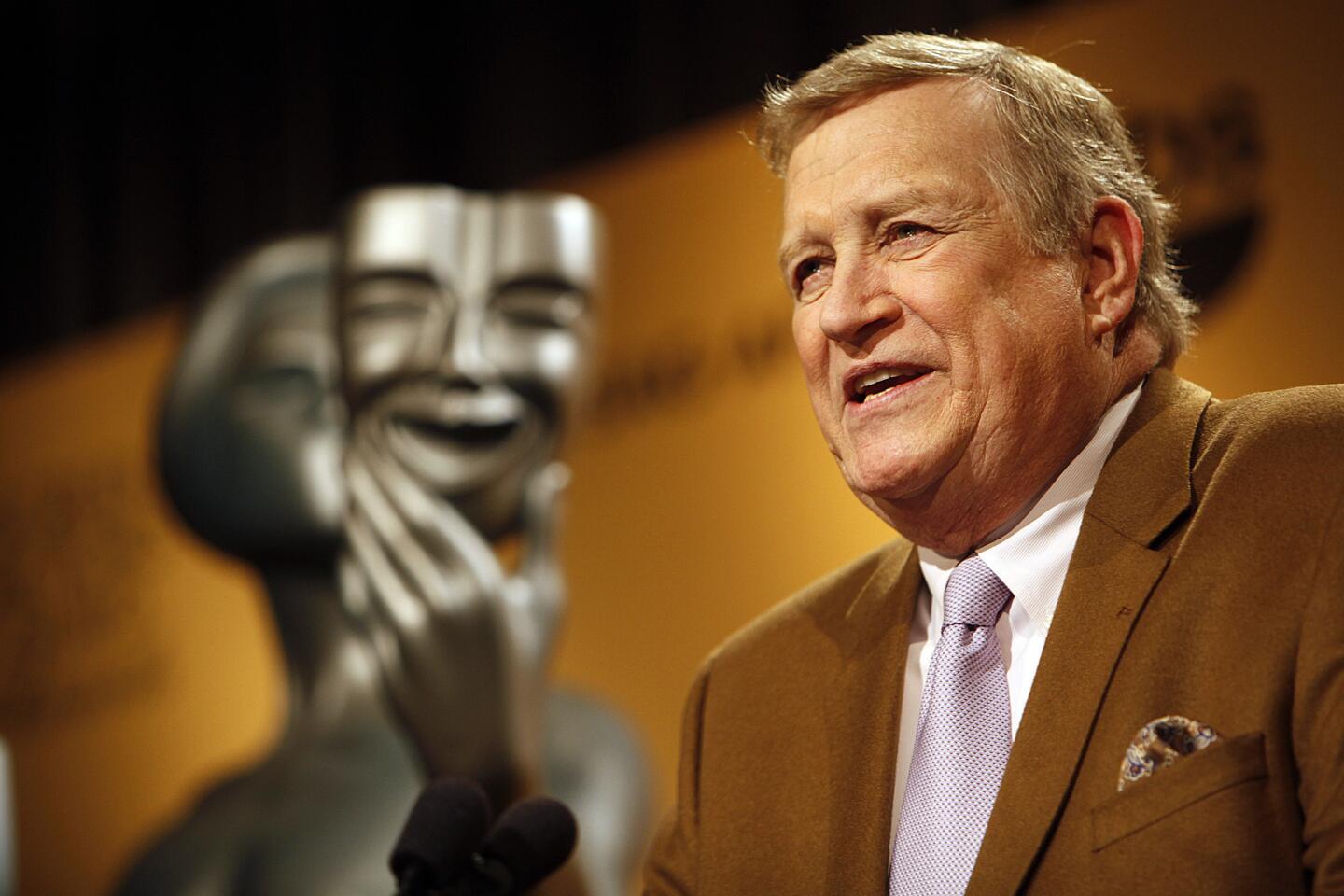

Ken Howard was president of SAG-AFTRA and an actor known for his role on TV’s ‘The White Shadow.’ He championed the merger of Hollywood’s two largest actors unions, which had a history of sparring. He was 71. Full obituary

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 51/61

The longtime Los Angeles radio disc jockey, whose real name was Art Ferguson, hosted the morning radio show for popular and influential station KHJ-AM in the late 1960s and went on to be a key player in the launch of latter-day powerhouses KROQ-AM and KIIS-FM. He was 71. Full obituary

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 52/61

The veteran actor built his early career playing heavies and won an Academy Award in 1968 for his supporting role as the tough Southern prison-camp convict who grew to hero-worship Paul Newman’s defiant title character in “Cool Hand Luke.” He was 91. Full obituary

(Warner Bros. / Getty Images) 53/61

A prolific entrepreneur, Mann over the course of seven decades founded 17 companies in fields ranging from aerospace to pharmaceuticals to medical devices. He was 90. Full obituary

(Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times) 54/61

The Egyptian diplomat helped negotiate his country’s landmark peace deal with Israel but then clashed with the United States when he served a single term as U.N. secretary-general. He was 93. Full obituary

(Marty Lederhandler / Associated Press) 55/61

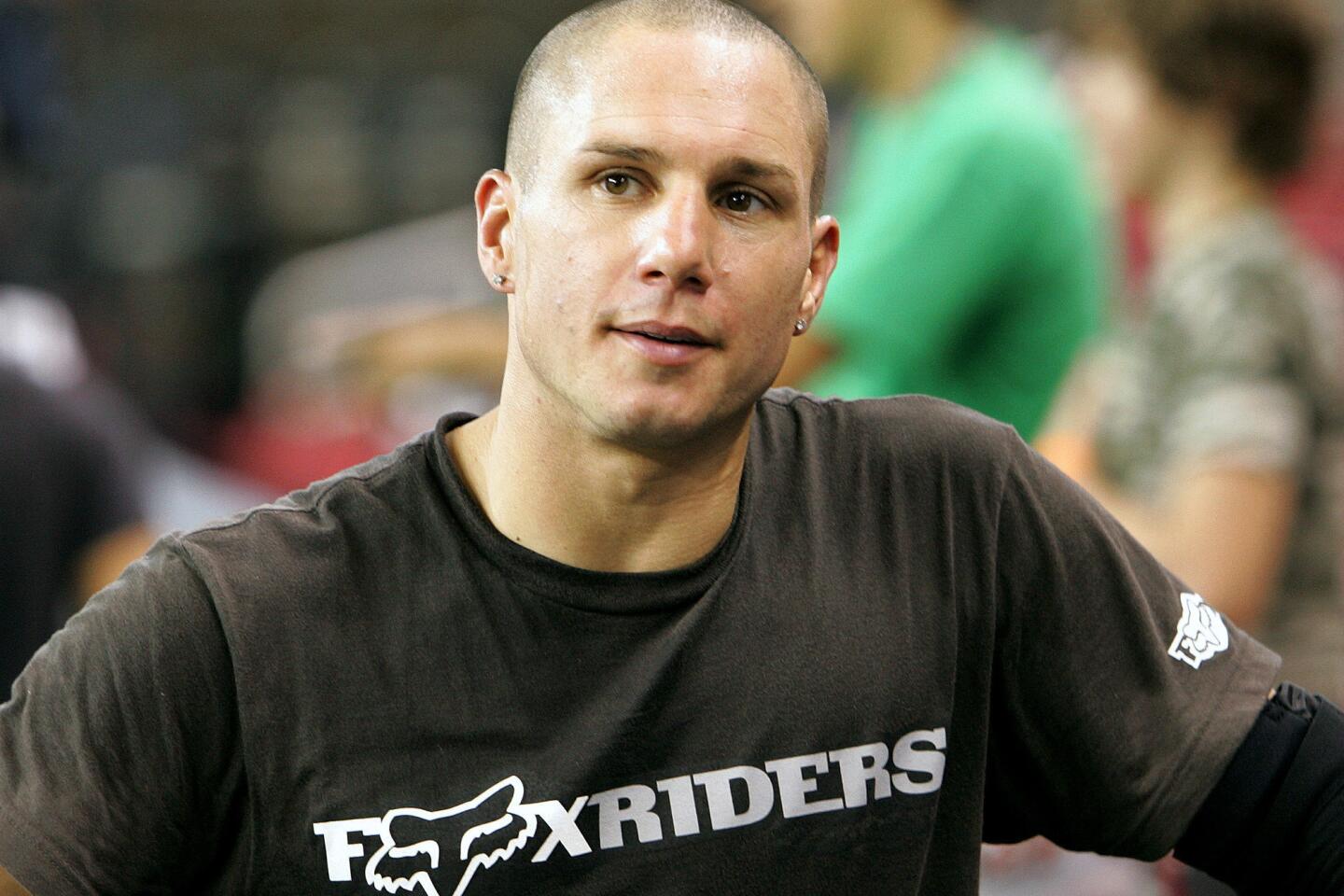

Pro-BMX biker Dave Mirra was one of the most decorated athletes in X Games history. He held the record for the most medals in history with 24. He was 41. Full obituary

(Ed Reinke / Associated Press) 56/61

Maurice White, co-founder and leader of the groundbreaking ensemble Earth, Wind & Fire, was the source for a wealth of euphoric hits in the 1970s and early ‘80s, including ‘Shining Star,’ ‘September,’ and ‘Boogie Wonderland.’ He was 74. Full obituary

(Kathy Willens / Associated Press) 57/61

In a career that encompassed everything from big-budget Hollywood movies to classical theater, Rickman made bad behavior fascinating to watch from “Die Hard” to the “Harry Potter” movies. He was 69. Full obituary

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times) 58/61

The composer and former principal conductor of the New York Philharmonic was known for pushing music lovers and the music establishment to let go of the past and embrace new sounds, structures and textures. He was 90. Full obituary

(Christophe Ena / Associated Press) 59/61

The Academy Award winner was revered as one of the most influential cinematographers in film history for his work on classics including “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” and “The Deer Hunter.” He was 85. Full obituary

(Tamas Kovacs / EPA) 60/61

Gordon helped revolutionize surfing with the creation of the foam surfboard. His polyurethane boards were lighter and easier to ride, making surfing accessible -- which helped popularize the sport globally. He was in his 70s. Full obituary

(Charlie Neuman / San Diego Union-Tribune/ZUMA Press) 61/61

The attorney and almond farmer was known for his battle to stop the $68-billion California bullet train project from slicing up his almond orchards -- part of a deeply emotional land war that has drawn in hundreds of farming families from Merced to Bakersfield. He was 92. Full obituary

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) He was born in Trenton, N.J., on March 11, 1936, the only child of a Sicilian immigrant who became a professor of Romance language at Brooklyn College and a mother who taught elementary school. He was known as “Nino” at home, and he carried the nickname throughout his life.

His family moved to the Queens borough of New York when he was a child. A star student, Scalia won a scholarship to a Jesuit-run military academy in Manhattan, and he recalled for the justices his high school days riding the New York subway carrying a rifle for drill practice. At the time of his Supreme Court appointment, a high school classmate observed: “This kid was a conservative when he was 17 years old. … He was brilliant, way above everybody else.”

However, he was rejected by Princeton University. “I was an Italian kid from Queens, not quite the Princeton type,” he said years later. Instead, he enrolled in Jesuit-run Georgetown University in Washington and graduated at the top of his class as its valedictorian in 1957. He went on to Harvard Law School and graduated in 1960. In Cambridge, he met and married Maureen McCarthy, a Radcliffe student.

Scalia began his career as a lawyer with the Jones, Day firm in Cleveland, but he switched directions and became a law professor at the University of Virginia in 1967. He joined the Nixon administration in 1971 as a mid-level lawyer, and he became head of the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel in August 1974 just as Nixon resigned and Gerald Ford became president. In those jobs Scalia won a reputation as being smart, combative and conservative. He also made influential friends, including Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld.

He left the government and returned to teaching law at the University of Chicago when Democrat Jimmy Carter became president in 1977. But after Ronald Reagan’s election, Scalia’s stock soared. He was named to the U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington. And in 1986, when Rehnquist was named to succeed Warren Burger as chief justice, Reagan chose Scalia to take Rehnquist’s seat.

Despite his conservative credentials, Scalia had an easy time at his Senate hearing. He coolly puffed on a pipe and joked with the senators. When Sen. Howard Metzenbaum, a fiery liberal Democrat from Ohio, noted that the nominee had beaten him on the tennis court, Scalia replied: “It was a case of my integrity overcoming my judgment, senator.” He drew a laugh and went on to win a unanimous confirmation. Years later, Scalia often marveled at his smooth ride in the Senate, and both he and his critics wondered whether he could have been confirmed at all in a more divided Senate.

During much of his tenure, Scalia’s influence within the court was limited to writing powerful dissents. His direct manner and combative style alienated some of his colleagues. He mocked opinions written by O’Connor and Kennedy, describing one of O’Connor’s abortion decisions as “absurd” and “not to be taken seriously.” He called one of Kennedy’s a “tutti-frutti opinion.”

They in turn were often reluctant to go along with Scalia in pushing the law to the right.

However, the conservative justices often came together in major cases, none better known than the 5-4 ruling that ended the recount of paper ballots in Florida and ensured a presidential victory for George W. Bush in 2000. Most lawyers had expected the high court to stay out of the post-election battle in Florida because the vote counting is governed by state law and because federal law says the House of Representatives will decide a disputed presidential election.

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

But acting on an emergency appeal from the Republicans, five justices, including Scalia, ordered a halt to the county-by-county recount in Florida on the grounds it could do “irreparable harm” to then-Gov. Bush. “The counting of votes that are of questionable legality does in my view threaten irreparable harm to petitioner Bush … by casting a cloud upon what he claims to be the legitimacy of his election,” Scalia wrote in the Saturday order.

Three days later, on Dec. 12, 2000, the court issued an unsigned opinion ending the recount, with four written dissents.

For years afterward, Scalia bristled when questioned about the Bush vs. Gore decision. “Get over it,” he replied.

Times staff writer Molly Hennessy-Fiske contributed to this report from El Paso, Texas.

MORE

Live updates: Reactions to Antonin Scalia’s death

Scalia’s death changes balance of high court, alters presidential campaign

From the archives: Obama unlikely to alter Supreme Court ideology with Republican Senate