Op-Ed: Algeria votes -- but for what?

Though the votes have not yet been counted in Thursday’s presidential election in Algeria, the result is all but decided: President Abdelaziz Bouteflika will win a fourth term.

Bouteflika’s long reign is unprecedented (and unconstitutional), and so is the nature of the election. The ailing and frail 77-year-old Bouteflika had not made a single public or televised campaign appearance until this month’s meeting with U.S. Secretary of State John F. Kerry, in which Bouteflika looked more dead than alive.

Indeed, one critic, novelist Yasmina Khadra, calls Bouteflika’s government a “zombie regime.” The president — a functionary of the National Liberation Front, the party that has owned Algeria since its independence in 1962 — is entrenched, propped up by generals and an uneasy status quo.

The question is, how long will the government manage to impose scripted elections on a population ready for the risks and rewards of an unscripted future?

Clearly, North Africa and Europe have a vital stake in Algeria’s stability and reliability. With its immense oil and natural gas reserves, Algeria is the European Union’s third-largest energy supplier, no small matter given Europe’s rocky relations with another energy supplier, Russia. Moreover, Algeria has the region’s largest economy, its largest population and its largest and best-trained army.

All of which contributed to Kerry’s photo op in Algeria: Bouteflika’s may be a zombie regime, but it’s our zombie regime.

Tellingly, this sentiment is shared by a number of older Algerians. Yes, Bouteflika had scarcely appeared or spoken in public since he suffered a stroke last year. But he remains the man who ended the “Black Decade,” the civil war that began in 1991 when the government canceled elections that an Islamic party was poised to win. By the end of the decade, 100,000 to 200,000 civilians had been killed.

Upon taking office after an election scarred by irregularities, Bouteflika stared down hard-liners within his own military and offered immunity to the Islamic militants if they would turn in their weapons and renounce terrorism.

“I do not think that we need a winner and a loser,” he declared. “Every drop of blood shed every day in Algeria is an Algerian drop of blood.”

Historian James Le Sueur describes what followed as a Pax Bouteflika. Powered by oil revenues and courted by the George W. Bush administration in the wake of 9/11, Bouteflika’s government gained international stature to go along with its domestic stability.

As one elderly Algerian who plans to vote for Bouteflika explained, “Even if he is old and sick, he brought peace and prosperity to the country.”

Both the peace and the prosperity, however, are fragile.

Not only does the question of Islam in political life still loom large, but there are also deepening ethnic tensions between Algeria’s Arab and Berber communities.

As for prosperity, little of it filters beyond le pouvoir (“the power”), the corrupt collaboration of the ruling party, the army generals and the secret police. They are steeped in petrodollars, while Algeria’s youth have been left high and dry: 25% of university graduates cannot find jobs.

During the Arab Spring, Algeria stood out for the tepidness of its demonstrations. It was as though the political liberalization in the late 1980s that led to the Black Decade immunized Algerians against hope for a true democracy.

Now Bouteflika’s run for a fourth term has reinforced passivity as much as protest. As one young Algerian in Paris told the journal Jeune Afrique, the election can change nothing: “The game is decided in the locker room.”

As a result, the presidential campaign has been as trivial as it is tragic.

After aborting his own run for president, Khadra published a noir novel, “What Are the Monkeys Waiting For?,” about a female cop investigating the gruesome murder of a young woman. The trail leads to Hamerlaine, an octogenarian ruler who embodies everything gone wrong in a state that has denied Algerians “the right to happiness in their own country.”

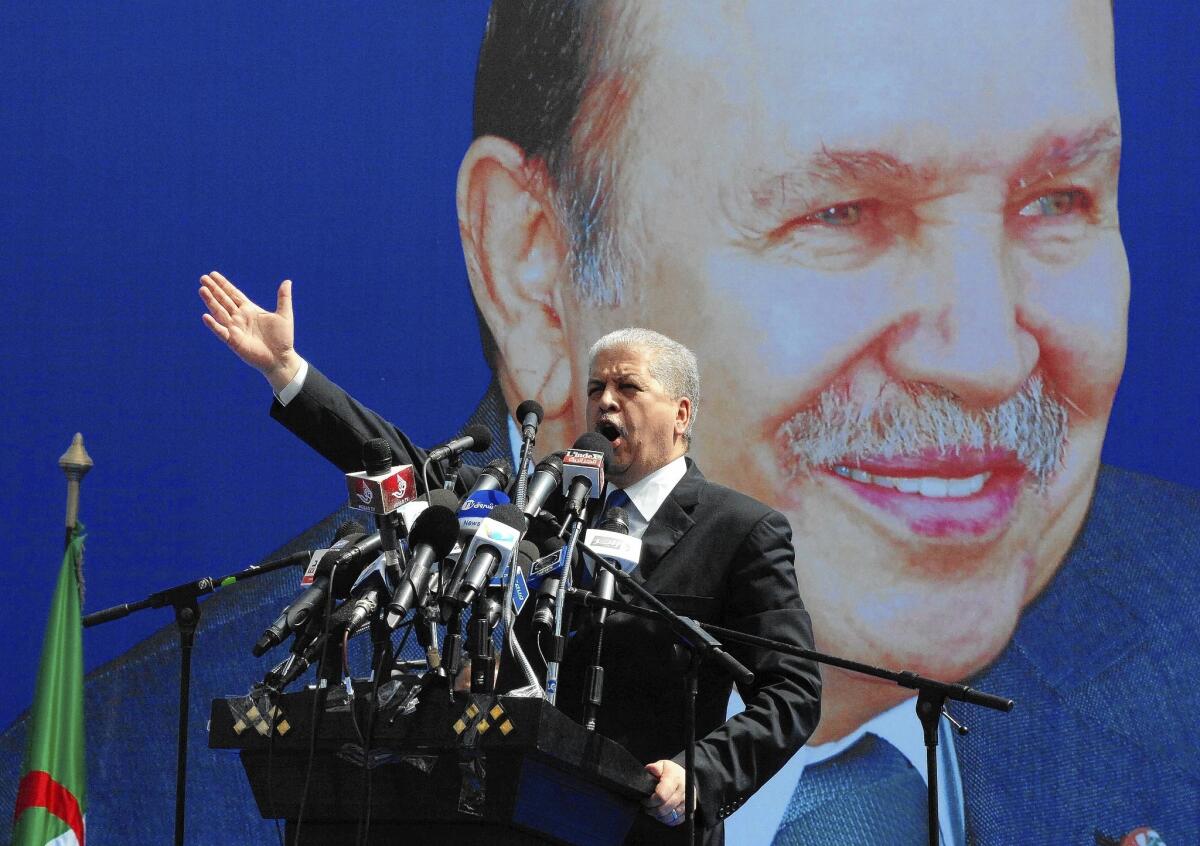

Campaign appearances by Bouteflika’s surrogates are poorly attended; some have been canceled for lack of bodies. At the same time, the one popular protest movement, Barakat (“Enough!” in an Algerian dialect), has had its greatest success among the Berbers, long alienated from the regime. Elsewhere, especially outside the cities, it is hardly known.

Bouteflika’s main opponent is Ali Benflis, whose reformist rhetoric is undermined by the fact that he, like Bouteflika, is a National Liberation Front careerist.

Indeed, for the Algerian writer Boualem Sansal, all of the candidates are little more than “hares” trained and kept by the state: They give the appearance of a race but could “just as easily stay at home.” The voters may well do exactly that Thursday.

In the contest between the power and the people, the outcome of the election may be foregone, but not the future. As the country’s most celebrated writer, Albert Camus, would remind Algeria’s youth: Although there is no reason to hope, that is no reason for despair.

Robert Zaretsky is a professor of French history at the University of Houston and the coauthor of “France and its Empire Since 1870.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.