Best of 2015: 2015’s peak sonic moments unfold at Poland’s Unsound fest and L.A.’s ‘9800’

Kode9

The year had a beginning. And in that moment, there was only one album I could listen to — D’Angelo’s “Black Messiah,” the soundtrack for my last winter in New York. Moving to L.A., though, erased much of what came before. When I think of 2015, the start date is a data glitch, reset to Sept. 1, when I moved to Angelino Heights and began hearing the city.

In November, I went to see Kendrick Lamar at the Wiltern. I showed up five minutes after the show had started, and walked straight into a throng of people waving towels and twisting and yelling out Lamar’s lyrics before he could. As much as I liked the show, none of the music was as intense as the immanent proof of so many people around me being present for the same thing at the same time.

The peak of my live music year, as in 2014, took place thousands of miles away from Los Angeles at the Unsound festival in Kraków. This didn’t happen twice in a row just because I am a sucker for music that sounds like amplified document shredders played in abandoned factories (though I am). Unsound has spread its remit wide, and when I went to Poland in October I found traces of America.

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour >>

RP Boo and Jlin, producers representing two generations of Chicago’s influential footwork scene, provided peak moments for me and many of the people who were only traveling a few miles to see the shows. Crowds in Kraków had no cool-factor problems — when it was time to go nuts, they went nuts, just like Lamar’s fans. Even better, I rarely had to strain to see through the tall grass of iPhones being held up.

Some of the best Unsound shows took place in a small, delicate theater in the Manggha Museum, which opened in 1994. The museum’s exhibitions are built from the collection of a local Polish collector who loved Japanese art. Its construction was funded by Polish film director Andrzej Wajda, the Japan Railway Workers’ Union, and their respective governments, a touching international alliance, especially now.

Guitarist Raphael Roginski, who has previously modified Eastern European folk and historical pockets of Jewish music, made one of the year’s most uncanny records. “Plays John Coltrane and Langston Hughes African Mystic Music” is a triple-filtered brew. The Langston Hughes bit is clear — on the album, vocalist Natalia Przybysz interprets Hughes poems like “Walkers With the Dawn” over Roginski’s guitar, with the words unmodified. What Roginski has taken from Coltrane is not obvious, though. His version of “Blue Train” suggests Coltrane’s well-known motif for only about two notes, and then slides off the map.

In his solo performance at Manggha, Roginski spoke a hybrid language. He plays a Gibson ES-335, a semi-hollow electric guitar common to jazz and rock ensembles. His modifications are just one unidentified pedal, the use of a capo and the insertion of a small piece of either paper or plastic — think skinny bookmark or long confetti — between the strings near the bridge. Combined with his finger picking, what Roginski produced bears little resemblance to the sound of Coltrane’s saxophone, and a very strong relationship to the trill of a West African kora with the tone of something muted like the mbira (thumb piano). His playing was rough, virtuosic, shaded, ecstatic and precise, summoning a lost volume of songs. A musician who grew up in Germany and Poland, whose father gambled and spoke Yiddish, he interpreted two African American visionaries and made it sound like a blend of several African traditions.

See more of Entertainment’s top stories on Facebook >>

Belgian producer and sound engineer Yves De Mey delivered one of the festival’s most restrained electronic sets at Manggha. De Mey is from no particular camp, in the best sense. His 2009 album, “Lichtung,” is a placid and stately blend of buzzes and rattles moving around slow electric guitar figures and what might be an organ. It’s music that could have been made without computers. His set at Manggha was utterly different, a blend of live synthesis and samples that suggested a descendant of club music slowed down and edited by a producer with exacting taste. His music was full of air and patience, never speeding up or building to any obvious climax. Surrounded by acts leaning on blown-out noise, De Mey suggested an intervention, an implicit proposal that producers listen more closely to their own work. I asked several people why I hadn’t heard of someone so good. Bill Kouligas, head of the exquisite PAN label, said, “He just doesn’t play the game.”

In 2015’s last quarter, local color was fairly intense. The Motown on Mondays night, run by DJ Expo and held at the Short Stop bar in Echo Park, was consistently strong. One of the biggest recent guests was Prince Paul, De La Soul producer and New York legend. For whatever reason, I danced harder at a night in September that was billed as a tribute to Soul Train, though the DJs went through all the stations of funk and soul in three hours, whether or not Don Cornelius was involved.

The Low End Theory, long one of the area’s most relevant nights, kept Wednesdays busy at the Airliner. In November, London’s Kode9 — known, when writing, under his born name Steve Goodman — appeared to play selections from his new album “Nothing,” accompanied by the Chicago footwork crew the Era. It was the kind of cross-generational combination that sounds optimistic on paper and then exceeds expectations. Scottish fortysomething producer creates music rooted in both dubstep’s echo and footwork’s chatter, hovering between the two at around 140 beats per minute. He shows up in L.A., with a crew of American dancers half his age, and somehow they all do their thing. And it worked. The lines blurred for a second and it was hard to sort out exactly where we were or what kind of music we were hearing.

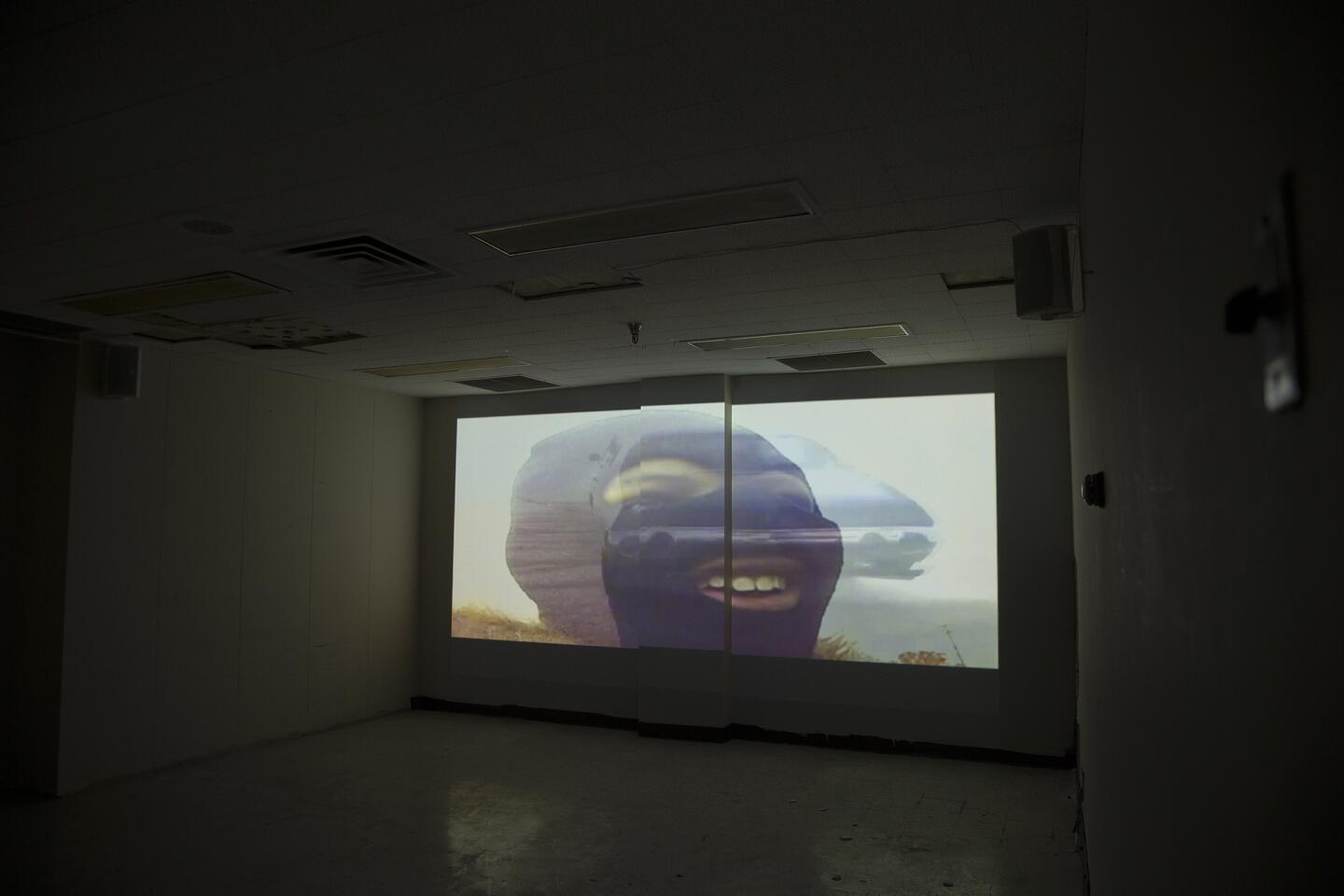

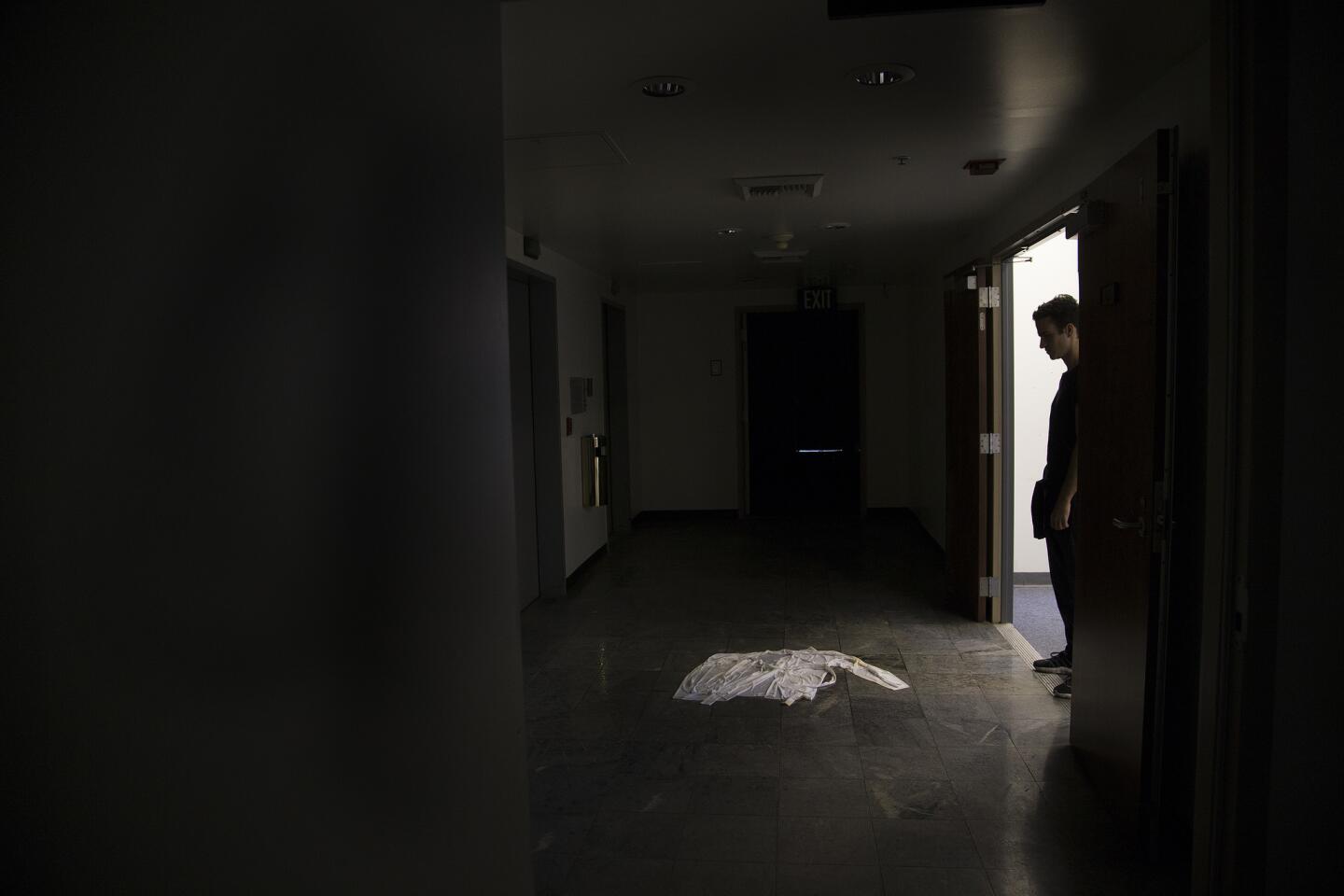

That disorientation was part of maybe my favorite single sound event, which wasn’t musical. For two weeks in October and November, an abandoned building at 9800 Sepulveda Blvd. was taken over by a baseball team of artists, organized by curator Shyan Rahimi. The building, designed in 1964 by Welton Becket, was originally intended to be part of LAX. From the outside, it’s a punchboard of tall half-rounded windows, with all-white cladding. Carlye Packer, one third of the Encyclopedia Inc. research project, pointed out to me that while Becket’s facade nods to the arcs and swooshes of Googie L.A. architecture it looks an awful lot like the Palazzo della Civiltá Italiana, built for Mussolini, and one of fascism’s better known architectural moments.

Inside, all the power bids are dead. Aside from the wood paneling and marble on the ground floor, the building is a monument to office malaise, floor after floor of wall-to-wall carpeting and toxic-looking dust. There were bits of detritus not yet cleared out that worked as their own found art: a 1995 copy of Byte magazine; a pile of rusted keys; acoustical tiling piled up like failed Christmas decorations.

On the fifth floor, curator Mara McKevitt brought out the ghosts with “A Gateway to Tomorrow,” a phrase borrowed from Becket’s original plans for the entire complex. In 18 abandoned offices, as many artists were both there and not there. Instructed to provide a recording of what they would do with the room if they were there, the contributors created a conference call from beyond. The rooms were no less ugly than before, lighted with the same fluorescent tubes that were there 20 years ago. Each audio source was stored in a small MP3 player connected to a pair of cheap desktop speakers. Some artists chose not to talk out their ideas, sending in recordings of looped music or noise.

The remaining voices, simply by virtue of using language, took the foreground and created an exquisite corpse of unrealized office worker dreams. “Full Apple box, half Apple box, quarter Apple box, 25-foot extension cord, 50-foot extension cord … Ziploc baggies and I would kind of neatly arrange them onto the wall of room R … my idea for the space, and this is a large imagining, I think, is first, I would demolish everything inside the building except for my room — and the foundational supports. Obviously.”

Twitter: @sfj

---------------------------------------

FOR THE RECORD

Dec. 22, 7:30 p.m.: An earlier version of this story stated that Steve Goodman, known as Kode9, is English. He is Scottish.

---------------------------------------

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.