Women, take back the Web! The sex abuse, threats are out of control

Are women disproportionately targeted for sexualized abuse on the Internet?

And if they are, can anything be done?

Yes, and maybe.

In a long, nuanced essay that has sparked a national conversation about the gendered nature of Internet threats, writer Amanda Hess used her own experience as the target of a relentless, abusive cyberstalker to explore why it is that women are so often savaged and threatened with sexual and other kinds of violence when they post, tweet and otherwise hold forth on the Internet.

“Why Women Aren’t Welcome on the Internet” appeared earlier this month in Pacific Standard. Of course, notes Hess, men are abused online too. It’s just that women, as she demonstrates over and over, are far more likely to be cyber brutalized:

“Just appearing as a woman online, it seems, can be enough to inspire abuse. In 2006, researchers from the University of Maryland set up a bunch of fake online accounts and then dispatched them into chat rooms. Accounts with feminine user names incurred an average of 100 sexually explicit or threatening messages a day. Masculine names received 3.7.”

She blows to bits the idea that the Internet is a self-contained virtual world whose borders do not bleed into the real world. She chronicles her own missed workdays, court appearances and expenses related to keeping her stalker at bay.

And she relates the story of Jessica Valenti, a popular feminist author and founder of the blog Feministing, whose work in the last seven years has prompted a flood of threats:

“When rape and death threats first started pouring into her inbox, she vacated her apartment for a week, changed her bank accounts, and got a new cell number. When the next wave of threats came, she got in touch with law enforcement officials, who warned her that though the men emailing her were unlikely to follow through on their threats, the level of vitriol indicated that she should be vigilant for a far less identifiable threat: silent ‘hunters’ who lurk behind the tweeting ‘hollerers.’ The FBI advised Valenti to leave her home until the threats blew over, to never walk outside of her apartment alone, and to keep aware of any cars or men who might show up repeatedly outside her door. ‘It was totally impossible advice,’ she says. ‘You have to be paranoid about everything. You can’t just not be in a public place.’ ”

But the threats don’t “blow over.” If you are a high-profile woman, this is the price of admission to the public conversation.

If you happen to be among the legions of women writing about politics – in the last election cycle, the press sections of some candidates’ planes and buses were dominated by women – you will find yourself under relentless attack by inflamed readers. The political stakes are so high, the partisan dysfunction is so intense, and on the Internet, inhibitions are so low. It’s a bad combo.

I confess I was somewhat skeptical that anything much has changed for women who dare speak their minds just because the medium is relatively new. The cretins have always been out there. As a newspaper columnist in the days before websites, I regularly received threats through good, old-fashioned snail mail. Lots of times, readers would take the time to clip my columns, deface them, then return them to me in a stamped envelope. Somewhere in my files, I still have an example. Someone drew horns on my head, a mustache over my lip and scrawled “Satan’s Little Whore” across the top. (The column was about gay rights.)

Later, the nasty stuff would arrive electronically.

Just last week, I got an email from someone calling me the C-word, preceded by the word “animal.” It is often suggested to me that I be raped or killed or dismembered. During the last presidential campaign, I was invited to kill myself any number of times. Surprisingly often, these missives come with fully identifiable addresses. People don’t even feel the need to hide their identities.

On Monday, in a New York Times opinion piece, “Life as a Female Journalist: Hot or Not,” journalist Amy Wallace, who has come in for her share of online abuse, recounted what happened to New York Times reporter Amy Harmon after she wrote about the struggle of a newly elected Kona city councilman to separate fact from emotion as his island debated a ban on genetically engineered crops. He concluded, Harmon reported, that some GMO opponents ignore science. An anti-GMO group, unhappy with the story, pasted Harmon’s face on a bikini-clad body and posted a photo of her on its Facebook page, holding hands with Monsanto’s chief executive. As Wallace wrote:

“So a few journalists get heckled, you may be thinking. Why should we care? Here’s why: This kind of vitriol is not designed to hold reporters accountable for the fairness and accuracy of their work. Instead, it seeks to intimidate and, ultimately, to silence female journalists who write about controversial topics. As often as not, even if they’ve won two Pulitzers, as Ms. Harmon has, these women find their bodies — not their intellects — under attack.”

I don’t know about silencing. I think it’s more about the perverse pleasure that comes from hating on someone you disagree with. It’s a metaphorical slap in the face, a punch in the nose. Haters gotta have someone to hate on.

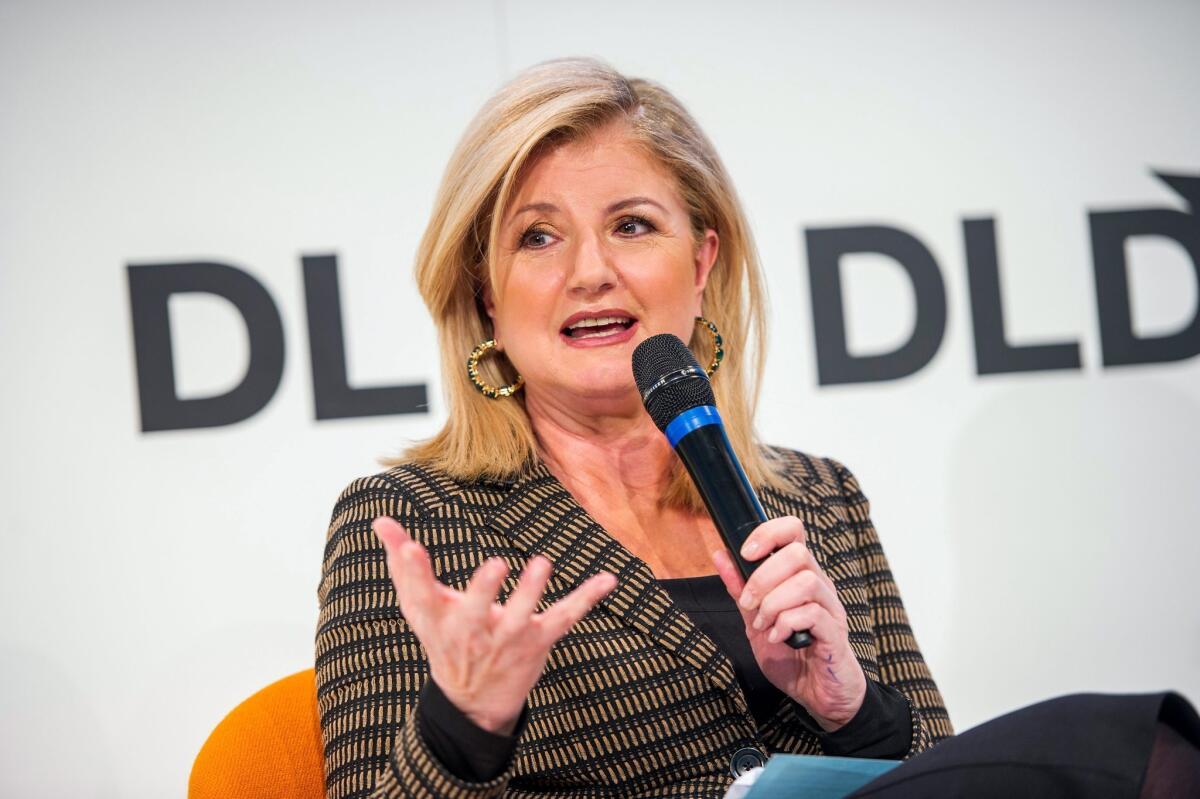

The late Andrew Breitbart, of all people, taught me that retweeting hateful tweets was an effective way to defuse their power. How did he learn to let the vile stuff roll off his back? By watching his one-time boss, Arianna Huffington, now one of the most powerful women on the Internet. She never let the haters get her down, he said.

Still, this discussion is not about hurt feelings, thin skins or getting a better sense of humor. It’s about stopping, or at least slowing, a certain kind of gender terrorism.

Hess finds hope in the work of Danielle Keats Citron, a University of Maryland law professor whose innovative 2009 Michigan Law Review article argued that recognizing “cyber gender harassment” for what it is, rather than trivializing it, is a critical first step in changing a culture that descends into misogyny with the tap of a computer key.

Citron advocates a new “cyber civil rights agenda.”

Women, take back the Web!

ALSO:

Chris Christie: Scandals are not my fault

Tone-deaf Sarah Palin says Obama plays race card

Twitter: @robinabcarian

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.