‘Pavement’s’ sincerity outshines the cheeky ‘Rocco’ in dance

Bar business wasn’t so hot at REDCAT on Saturday night a half-hour before the show. The crowd had already lined up waiting for the doors to the theater to open. Word had gotten out that early birds would get ringside seats for “Rocco.” The dance by Emio Greco and Pieter C. Scholten from Amsterdam takes place in a boxing ring and was inspired by the classic Italian film “Rocco and His Brothers.”

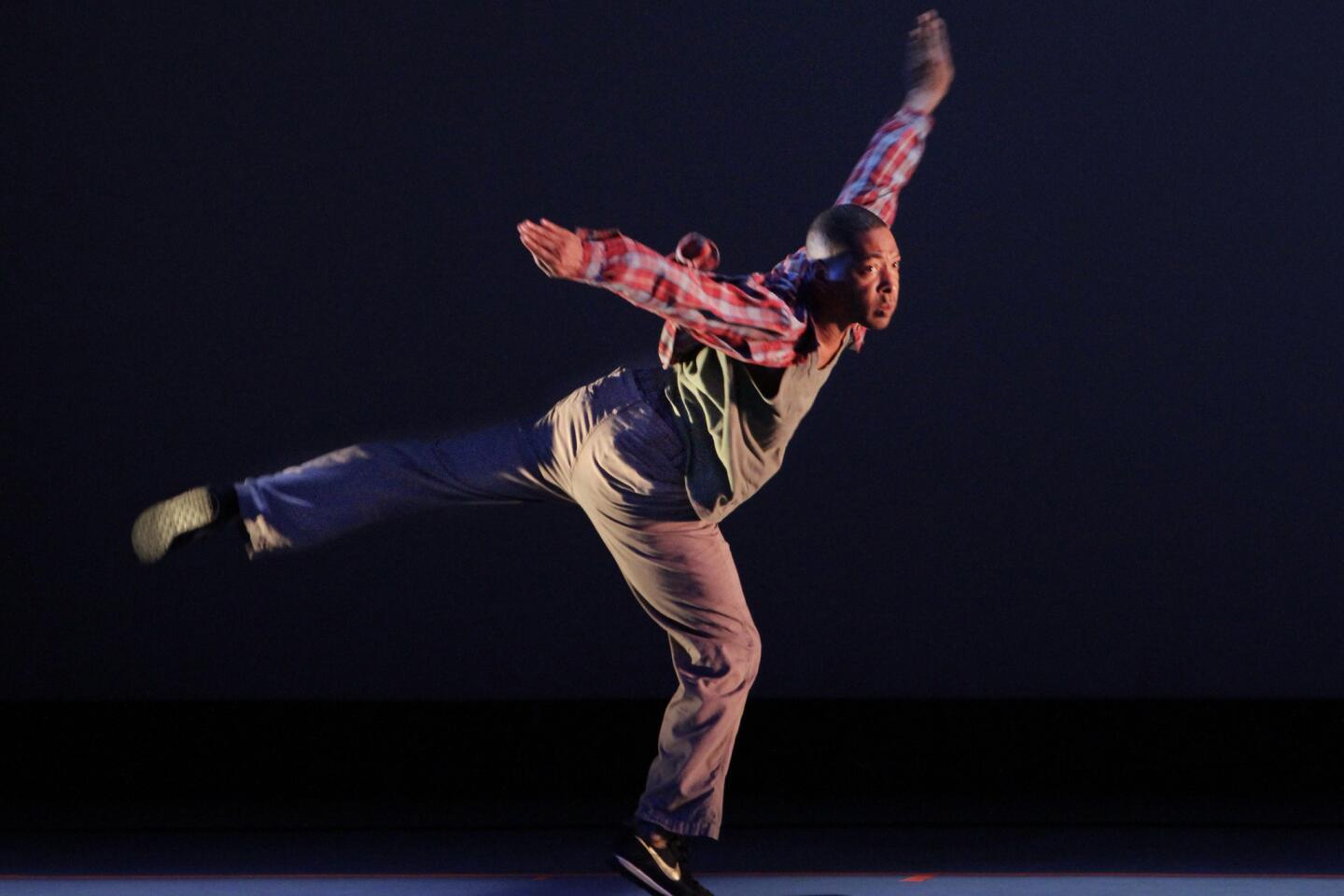

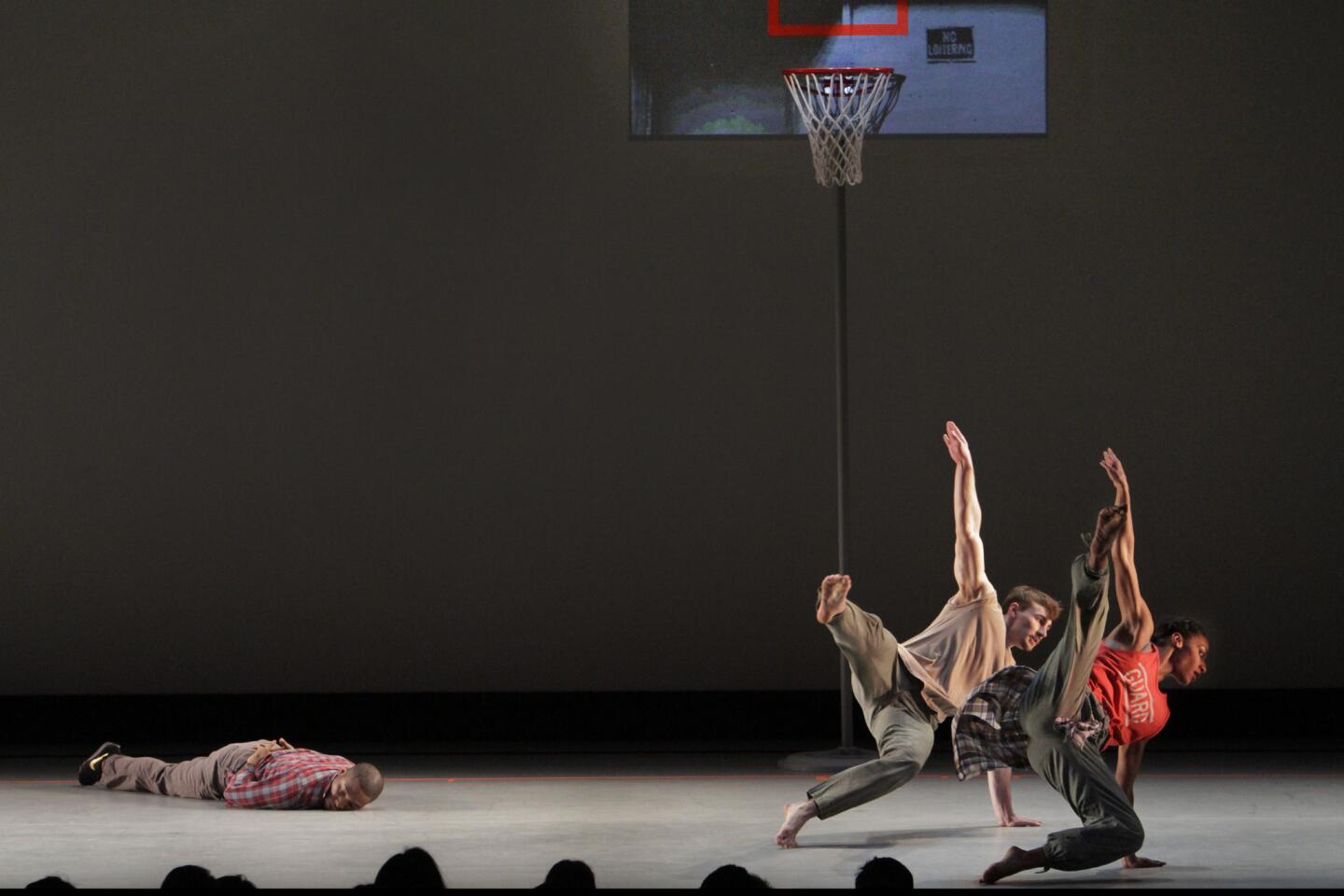

Three nights later the Campbell Hall stage at UC-Santa Barbara was transformed into a basketball court for “Pavement.” Kyle Abraham’s dance, inspired by the film “Boyz N the Hood,” was given its West Coast premiere on UCSB’s Arts & Lectures series.

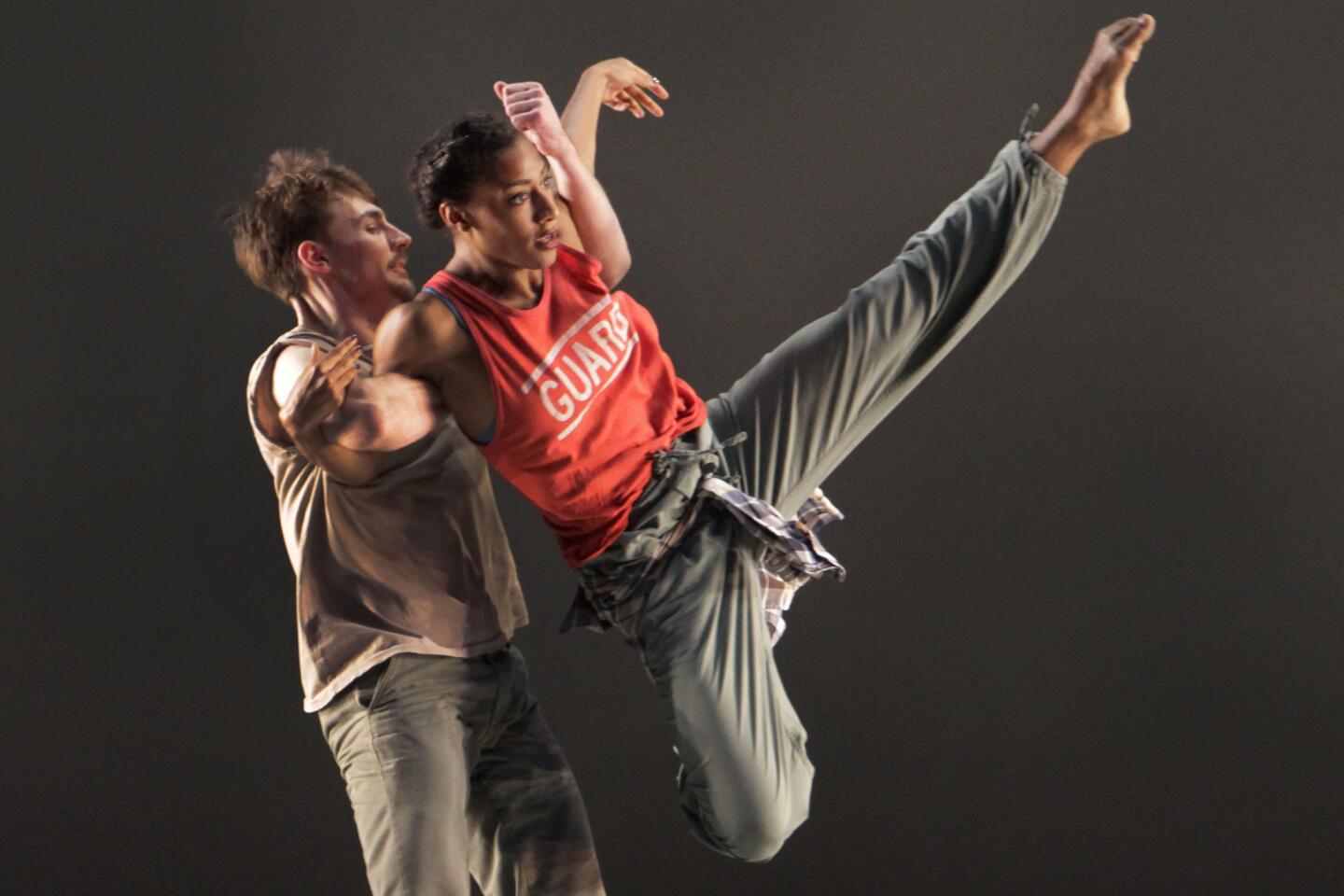

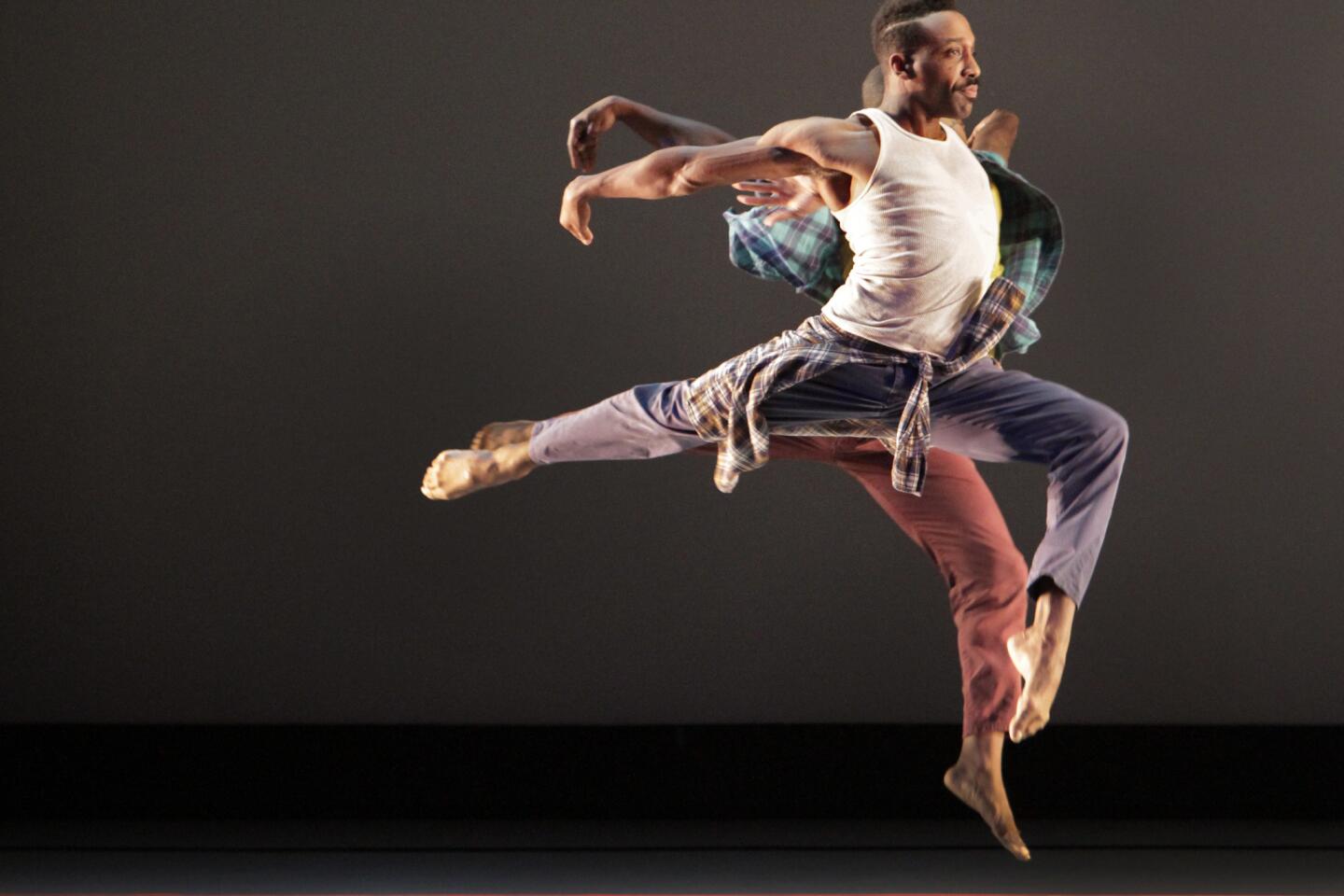

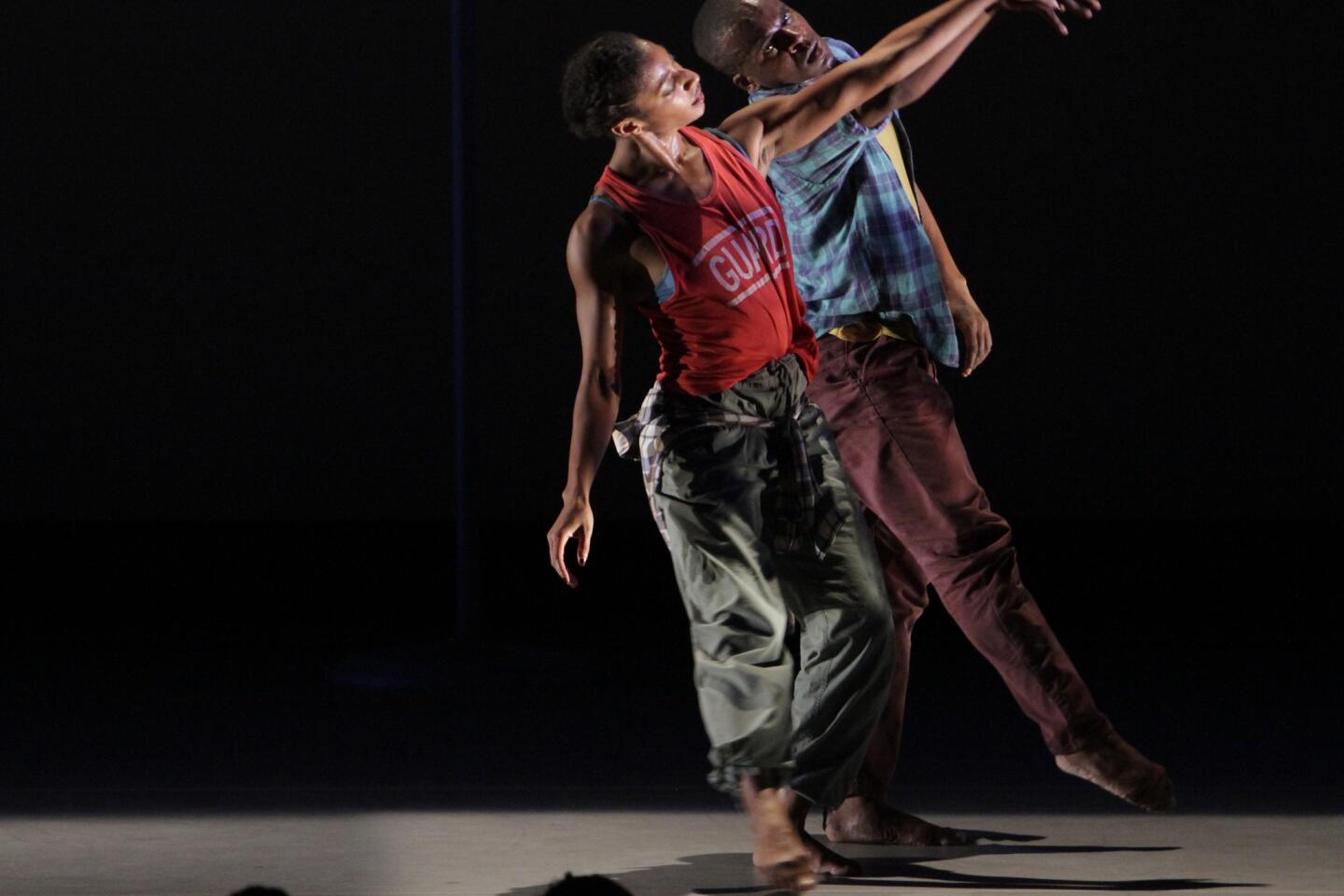

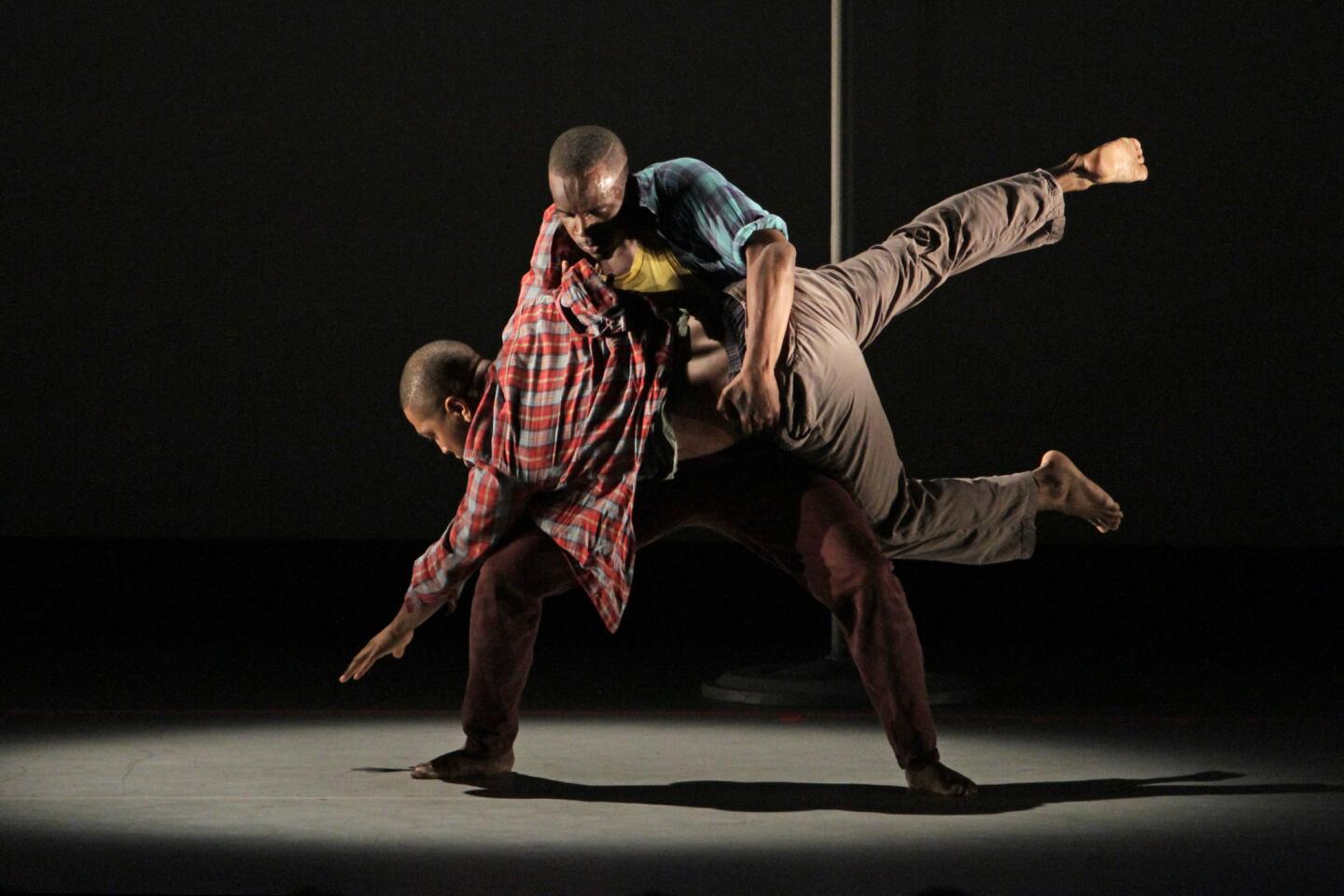

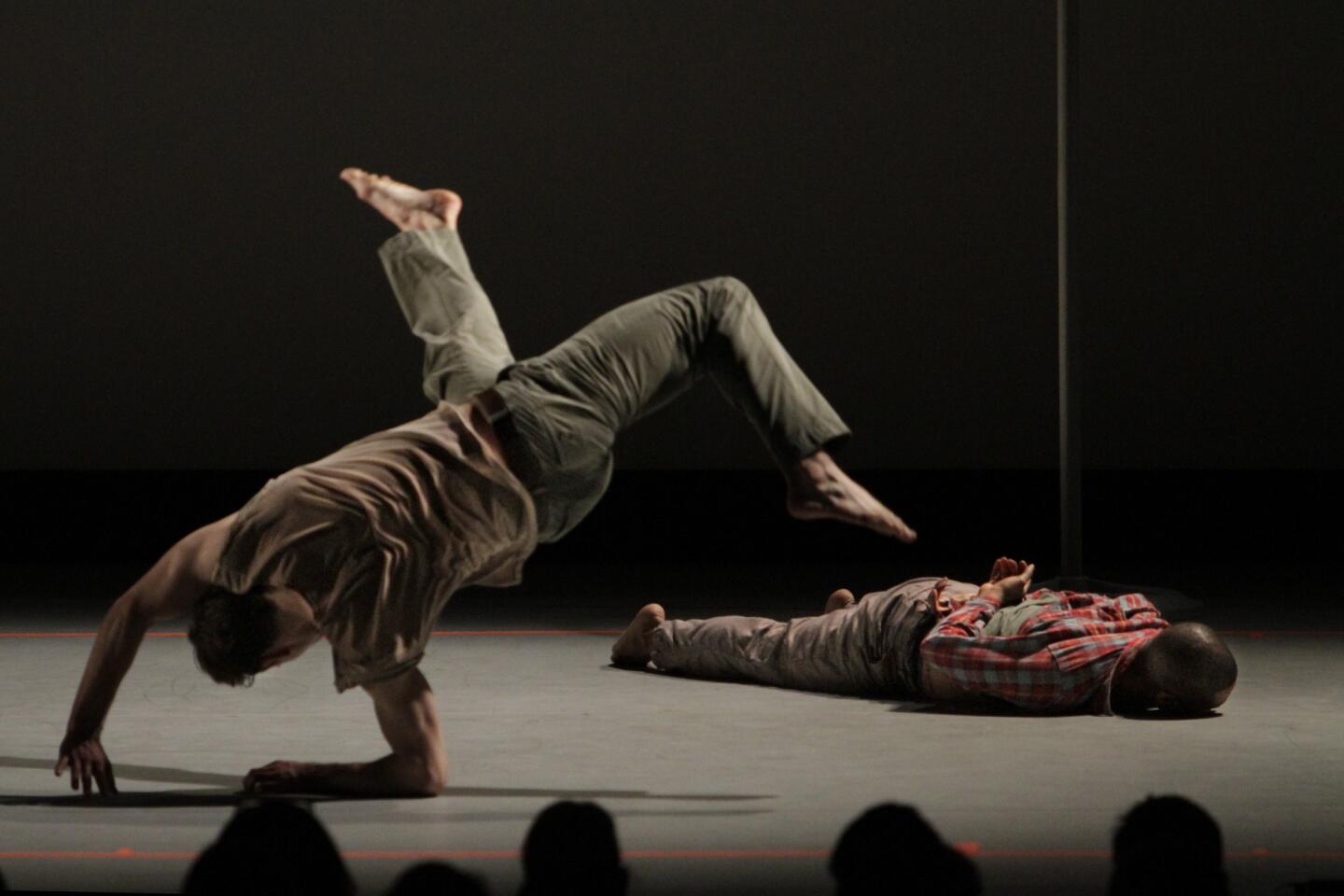

Both dances dealt with brothers, be they familial or racial. The two companies, ICKAmsterdam and Abraham.In.Motion, featured brilliantly athletic performances, physically and emotionally draining, with chaotically eclectic movement.

PHOTOS: ‘Pavement’ by Kyle Abraham

Each dance relied on an equally eclectic recorded score in which electronica or hip-hop was intercut with Baroque music and romantic pop. Each piece lasted just under an hour. Each event attracted a large and keen young audience. Oh, and both works were made in 2012.

So is sports-based, movie-based, pop-Baroque dance dealing with social breakdown a hot new international trend?

Not exactly, in that Greco and Scholten bring a different sensibility and cultural attitude to “Rocco” than does Abraham to “Pavement.” What proved interesting about the coincidence, though, was how far more effective Abraham’s earnest approach seemed in relation to the caustic cheekiness of Greco and Scholten.

If there is a trend, it may be that irony has gotten old. And that Abraham, who was a recipient of the 2013 MacArthur Fellowship and deemed the hottest new New York choreographer, really does have something fresh to offer.

Unlike “Pavement,” which is a meditation on “Boyz N the Hood” and street life in L.A.’s Crenshaw district, little of Luchino Visconti’s 1960 film, about four brothers from the south of Italy who move to Milan where two take up boxing, is evident in “Rocco.”

CRITICS’ PICKS: What to watch, where to go, what to eat

The impetus for “Pavement” was the profound effect that “Boyz” had on Abraham when he saw it as a teenager in Pittsburgh and attempting to make sense of what it meant to be growing up as a black American male in 1991. The origins of “Rocco,” on the other hand, were as a dance sequence for a theatrical production of “Rocco and His Brothers” that never materialized.

“Rocco” then became a kind of abstracted “Rocco.” Four dancers stand in for the four Italian brothers but are almost meant to represent, according to the choreographers, “brotherly love in all its facets: the good and the bad, the devil and the angel, the androgynous and the incestuous, Cain and Abel, Romulus and Remus, Laurel and Hardy.”

That’s a lot of cultural baggage, and you would have to dig deep to uncover any of it. “Rocco” begins with two boxers in mouse suits running through the audience maniacally. They’re homoerotic mice who later strip to glittery camp costumes and perform a campy routine lip-syncing to a tacky French chanson.

The main contenders, two boxers in trunks, are shadow boxers—– mirroring each other’s jerky, shaking, bounding, falling, flailing, flitting movements, exhaustively and exhaustingly. Their endurance is impressive. Emotions are momentary. Eventually they wear themselves out, and what we are left with is weariness.

The set for “Pavement” is a court with a basketball hoop on which film of tenement buildings can be projected. Much movement in “Rocco” has the quality of postmodern cliché, and Abraham is, if anything, less original in his dance language. But the contexts are new. In Abraham’s case the old is not tired but becomes original when irony is replaced by ambiguity.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

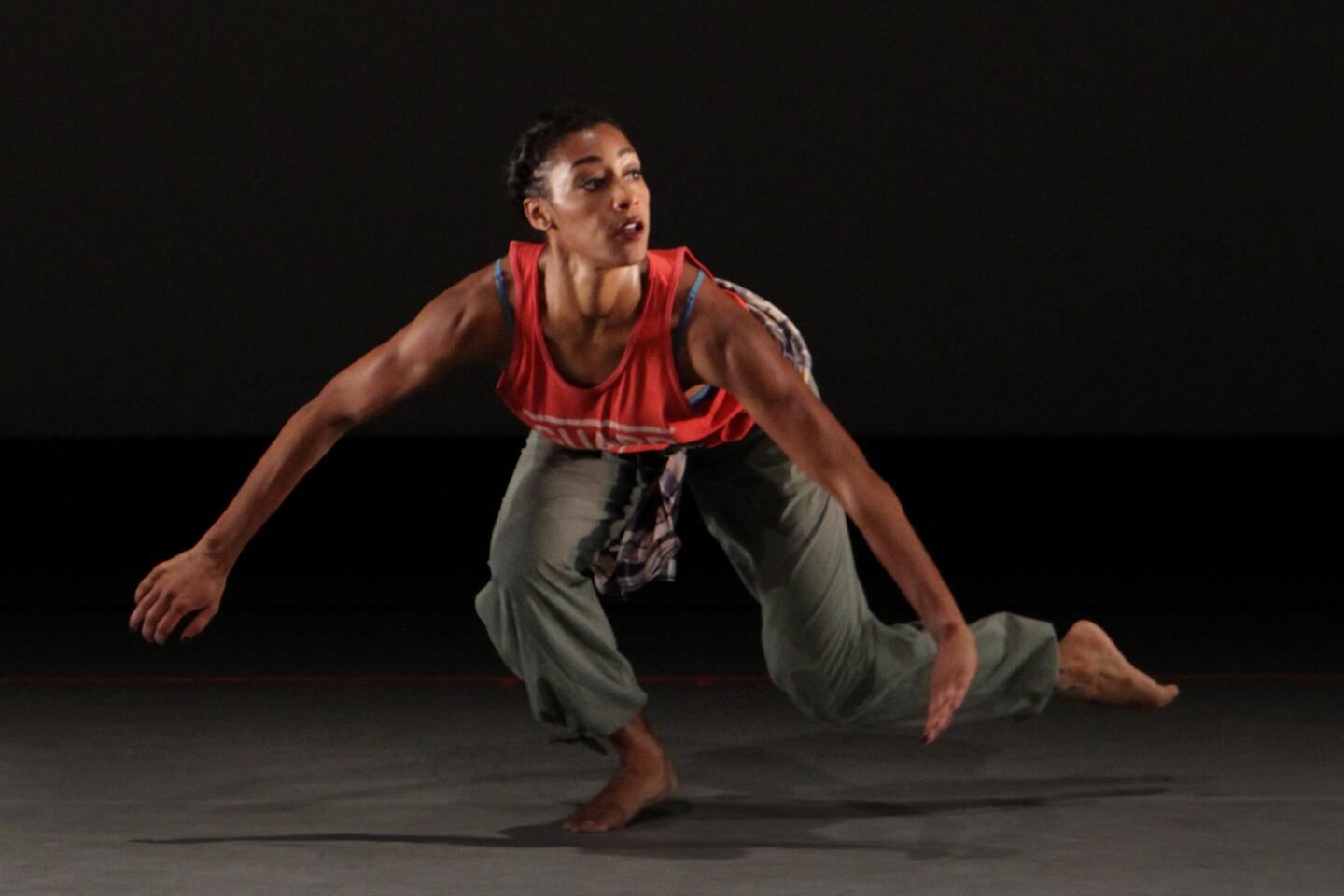

Abraham contemplates the urban situation of the black male with a disconcerting yet natural ebb and flow. Relationships are simply not quantifiable. His company includes three black male dancers (Abraham being one), two white males and a single woman (black). Gender and race are conditions of fluidity. Who’s a brother? What’s a brother? These things are neither explicit nor consistent.

The center of “Pavement” is Abraham’s radiance onstage. He creates a kind of glow that reflects on all he comes in contact with. He mixes movement styles with an effortless-seeming smoothness and grace present even — and especially — when the dance turns violent.

Bits of “Boyz N the Hood” find their way onto the court either through excerpts of the soundtrack of the film or the dancers themselves employing street language. The score is full of musical and cultural disconnects. Abraham has a fondness for countertenors singing Caldera and for Sam Cooke. Sweetness and anger must contend. Often a body lies long onstage. At the end, with Britten’s “Peter Grimes” heard through the loudspeakers, the court holds piles of bodies (the “tiramisu moment,” one of the dancers joked in a post-performance conversation with the audience).

Abraham’s genius, though, is to find the elusive slot where various cultural references, and where high art and low, are not, like these boyz (and girl) in the hood, at odds with society or with themselves. This is the elusive slot where the spiritual can slip in, barely sensed, but changing everything. Rather than weariness, “Pavement” paves the way for new life.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.