L.A., Santa Monica buildings may sit atop quake faults

The cities have approved several construction projects along two well-known faults in recent years without requiring seismic studies.

T

he cities of Los Angeles and Santa Monica in the last decade have approved more than a dozen construction projects on or near two well-known faults without requiring seismic studies to determine if the buildings could be destroyed in an earthquake, according to a Times analysis.

Los Angeles building records show that when officials approved projects, they used outdated information that placed the Santa Monica and Hollywood faults much farther away from the developments.

The structures include a 49-unit apartment complex on the Westside and a three-story office building near the Mormon temple, whose landmark hill was formed by the Santa Monica fault.

State law prohibits construction on top of faults and requires extensive studies before approval of any building within about 500 feet of faults zoned by the state. But the state has not created fault zones for the neighborhoods around the Hollywood or Santa Monica faults, so the cities are not required to enforce the law there.

City officials could have demanded extensive underground digging to determine whether a fault lies under a development before allowing the projects. Instead, they accepted the developers' geology reports and concluded that fault studies were not required.

The failure to investigate the faults heightens questions raised in recent months about whether city and state governments are doing enough to ensure buildings can withstand major quakes. The Times reported this fall that L.A. officials admitted they have been using outdated fault maps. They didn't realize their error until Times reporters pointed it out to them, and they have since begun using newer state maps.

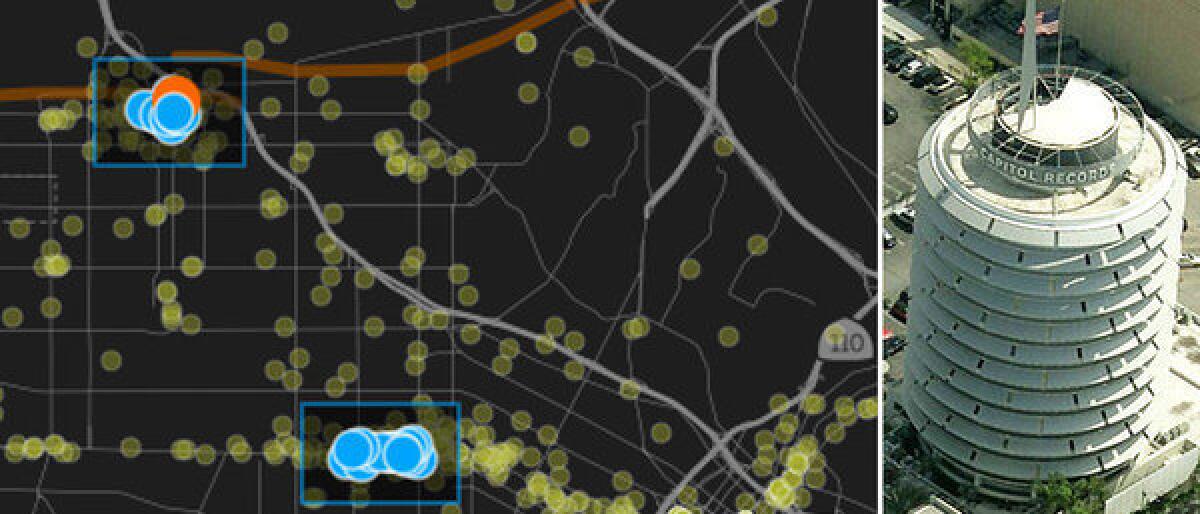

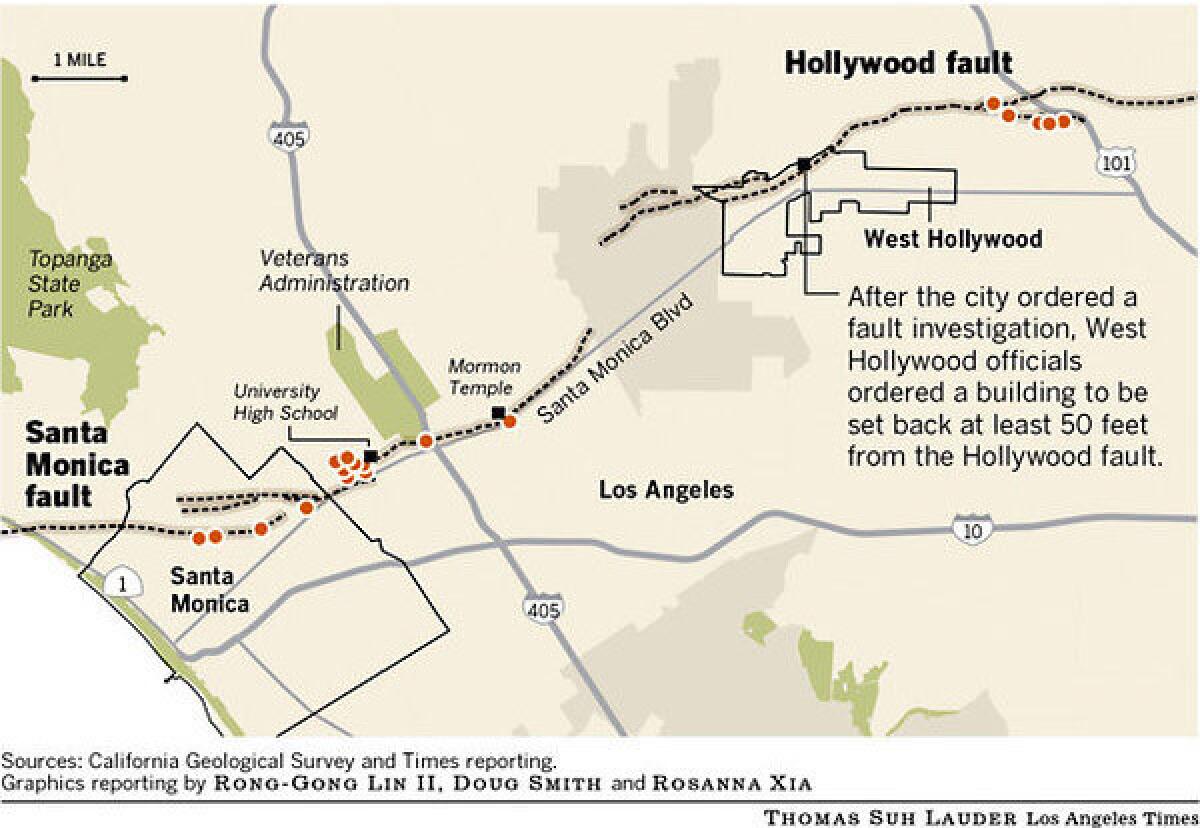

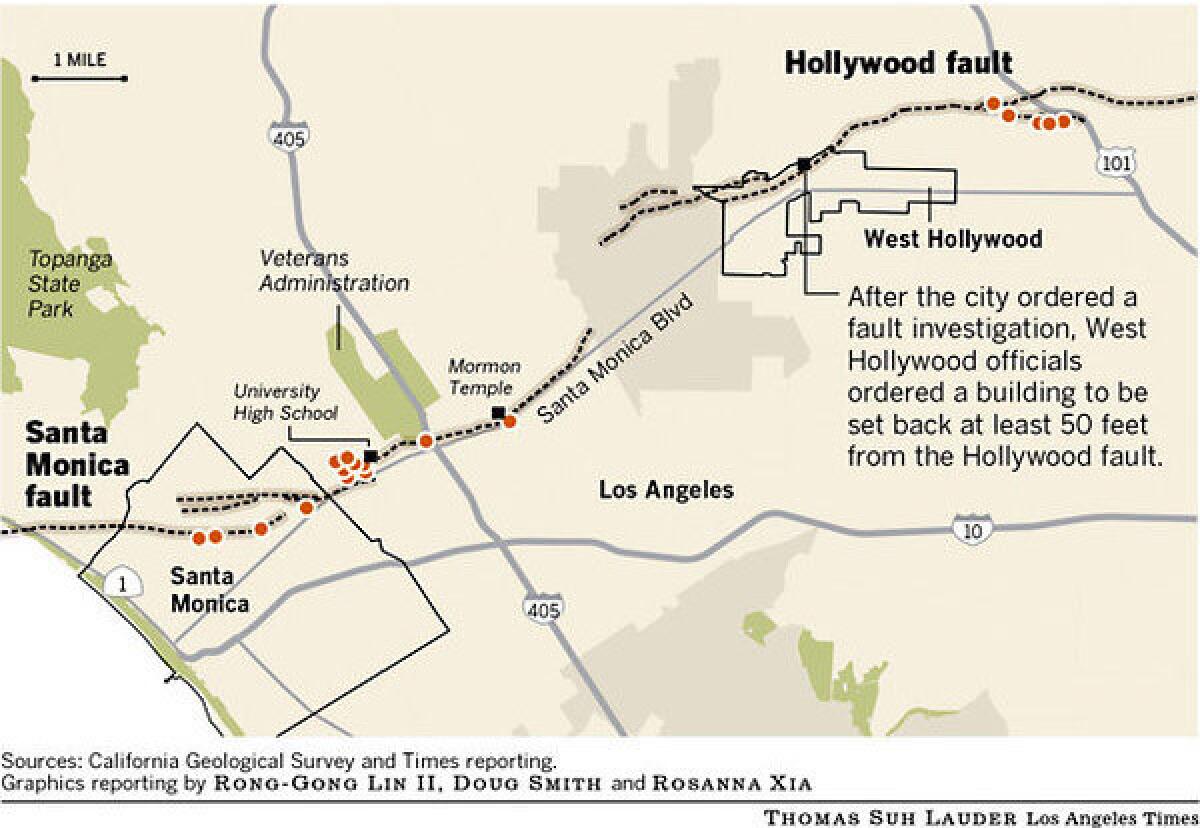

A Times survey found 14 buildings in Los Angeles and four in Santa Monica, shown above with orange markers, constructed close to two active earthquake faults not yet zoned by the state. Budget cuts have stalled regulations on the faults.

The state, meanwhile, still has about 300 fault maps to draw across California. Its program for mapping faults virtually halted in the 1990s because of budget cuts, and there is no timeline or money set aside for completing the work.

The Hollywood and Santa Monica faults pass through some of the priciest real estate in Southern California, running from central Hollywood, through West Hollywood and Beverly Hills and into Westwood and Santa Monica. Scientists have extensively studied both faults for decades. As early as 1997, they produced detailed — and widely available — maps that estimate the paths.

A Times analysis estimated that there are roughly 1,400 buildings on or next to the Santa Monica and Hollywood faults. Many of them were built before the state law banning construction on top of faults was approved in 1972.

Seismic safety experts have long warned that a big earthquake is capable of severely damaging buildings if they are on a fault. During the 1971 Sylmar quake, one side of the San Fernando fault shifted as much as eight feet. About 80% of the buildings along the fault suffered severe to moderate damage.

"Why would one risk constructing multimillion-dollar investments on ground that is known to be of very high hazard, and place in jeopardy the lives of those who inhabit the building?" said John Parrish, the state geologist.

It's critical that you understand where active faults are and, equally important, where they are not."— James Dolan, USC earth sciences professor

The Times analysis focused on projects built along the Hollywood and Santa Monica faults during the 2000s to determine how much construction occurred while the state's mapping program was dormant. Reporters walked and drove along the paths of the faults, compiled a list of recent construction projects approved over the last decade, and reviewed city building records. The survey found 18 projects built along the faults during this period, 14 in Los Angeles and four in Santa Monica.

Los Angeles approved a 49-unit apartment building now under construction at 1301-1317 Brockton Ave. near West Los Angeles. The property sits on a hill near University High School. The hill, created thousands of years ago as one side of the Santa Monica fault pushed up against the other, is often cited by geologists as a prominent example of earthquake activity in Los Angeles.

The developer submitted a report to the city saying the fault was 1.9 miles away from the property. But the most recent state map, released in 2010, suggests the fault could sit directly under the apartments. A representative for the Brockton project did not return several calls or reply to a letter seeking comment.

The city approved the apartments without first requiring underground digging to find out whether the fault ran through the property.

By contrast, the Los Angeles Unified School District began extensive quake tests in the late 1990s. After pinpointing the exact location of the Santa Monica fault, the district ordered the gym and music buildings torn down at University High School, saying they posed too great a risk to students.

Another apartment building under construction near West Los Angeles wasn't scrutinized either. The state's map shows that the Santa Monica fault could be under the site of the four-story, 63-unit structure at 1523-1547 Beloit Ave. But the developer's geology reports, submitted to the city and reviewed by The Times, didn't mention any fault risk.

Apartments being built on Brockton Avenue might sit directly above a fault, a state map suggests.

Apartment project manager Michael Cohanzad said he didn't know the Santa Monica fault was nearby when the property was purchased. He said that the city did not ask for a fault investigation and that the project met all city requirements.

Luke Zamperini, a spokesman for the Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety, said that because the Santa Monica fault doesn't have an official zone designation from the state, no further seismic studies were required.

A few miles to the southwest, officials in the city of Santa Monica approved construction of a Whole Foods Market, which opened in 2003, despite warnings from geologists that the market site on Wilshire Boulevard might sit on top of a fault. The geologists recommended digging across the site to determine whether it is there. City building records show no evidence city officials followed their advice or ordered more investigation.

Ron Takiguchi, Santa Monica's top building official, said the city did not order fault investigations for any of the four projects identified by The Times. The city is diligent about examining earthquake risks and relies on experts in making its decisions, he said.

Marci Frumkin, a spokeswoman for Whole Foods Market, said the company rents the building and is aware of potential dangers.

"We know of the seismic risk and have done extensive retrofitting to the building," she said. She did not provide details.

Building owner Dave Larner said he does not believe the market is on top of the fault, adding: "The building was built to exceed or meet all specifications."

The Times survey found that only one city — West Hollywood — required extensive seismic investigation before allowing construction along a fault. In at least two cases, the city required developers to move the locations of proposed buildings after finding that they would sit atop a strand of the fault.

A 1997 investigation ordered by West Hollywood uncovered the Hollywood fault underneath a proposed five-story development on Sunset Boulevard. West Hollywood ordered the building to be set back at least 50 feet from the fault, city planning official John Keho said.

Government institutions for years have grappled with what to do about structures built on top of faults.

Citing safety concerns, Los Angeles Southwest College demolished two buildings in 1991 that straddled the Newport-Inglewood fault. And L.A. Unified tore down a portion of the downtown Belmont Learning Center after a fault was discovered. The Belmont case triggered a districtwide study of potential fault dangers and led to plans to demolish unsafe buildings at schools on top of a fault, including those at University High. The school district allocated at least $100 million for the projects.

Los Angeles' regulation of development along faults came under increased scrutiny this year from residents and state officials when the City Council approved the controversial Millennium Hollywood skyscraper project on a site very close to the Hollywood fault. The city did require some seismic testing but no underground trenching to determine whether the fault ran under the site.

Amid questions over the safety of the development, the city has now ordered a full trench study and state officials accelerated its zoning around the Hollywood fault, which will be completed by 2014.

USC earth sciences professor James Dolan, whose maps of the Hollywood and Santa Monica faults drawn in the 1990s were later adopted by the state, said extensive seismic research should be conducted before any new buildings are approved near faults.

The Mormon temple, whose landmark hill was formed by the Santa Monica fault.

"It's just common sense," Dolan said. "It's critical that you understand where active faults are and, equally important, where they are not."

Many of those who live and work along the two faults take the potential danger in stride. Some said they feel safe because their buildings are new and constructed in compliance with the latest building regulations.

In the shadow of the Mormon temple, developers built an office complex that, state maps suggest, could be within 300 feet of the Santa Monica fault. The owner said the building complied with all city requirements. Some tenants said they didn't know the fault was nearby but were not overly concerned.

"This building is brand new. We don't feel any danger," said Michael Chau, office manager for Vision Dental. "We don't think about earthquakes, really."

Contact the reporters | Contact the photographer

Follow us on Twitter:

Great Reads from The Times (@latgreatreads)

More coverage of earthquake safety issues

Many older L.A. buildings could collapse in an earthquake

Concrete columns supporting the stairwells of Olive View Medical Center failed because there was too little steel reinforcement. After the 1971 Sylmar earthquake, county officials toured the destruction.

The question is, do we have to have lots of people die in order to make this change?"

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.