Border Patrol agents, facing scrutiny over shootings, have harsh words for their leaders

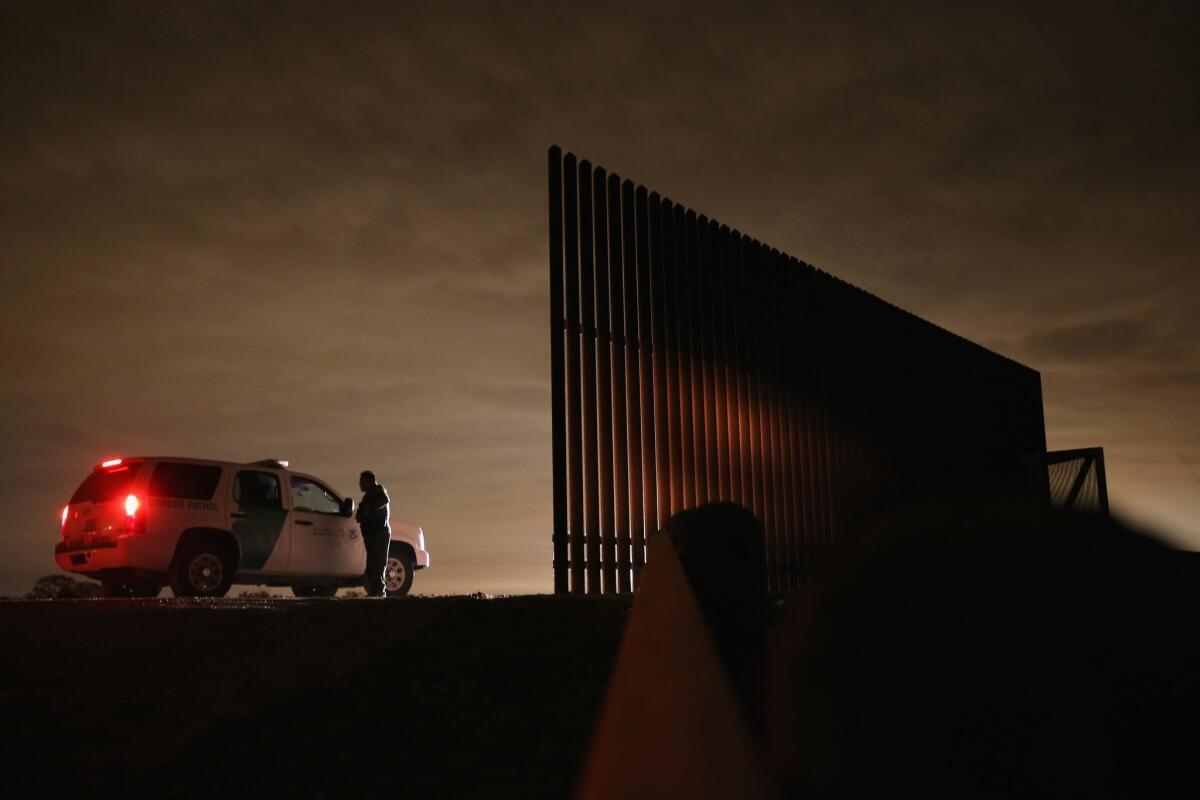

Border Patrol agents near a section of U.S.-Mexico border fence in La Joya, Texas. This week, the union representing agents complained of poor leadership by agency officials.

Rank-and-file Border Patrol agents are furious that they have lost some of their favorite enforcement tools and say that intense public criticism of border shootings has led to a morale crisis.

“We lack the political will to enforce the law and allow our agency to be effective,” said National Border Patrol Council spokesman Shawn Moran in a conference call with reporters Wednesday. The call was coordinated by the union that represents the agents.

Among the most far-reaching and damning accusations from agents working entry points in Arizona, Texas and California was that the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol administration in Washington does not want agents to make drug busts and has taken away their ability to do so.

Shane Gallagher, an agent in the San Diego sector, said roving interdiction patrols — in which agents would stop suspicious vehicles north of the border — were extraordinarily successful at nabbing border crossers with drugs. But those patrols would then create uncomfortable questions for the ports through which the vehicles had just passed, he said.

“Now the port of entry has to explain who was in the primary lane, what actions were taken, if the vehicle was inspected, so you can see there’s a whole host of implications,” he said.

Though rank-and-file agents saw the value in drug interdictions, Gallagher said, agency leadership did not and drastically reduced the number of agents doing such work.

“There was a lot of pressure for us to get out of the [drug] interdiction game,” Gallagher said.

The decision to speak with reporters comes as rank-and-file agents have come under intense criticism for their involvement in fatal cross-border shootings – including the slaying of a 15-year-old boy who was walking home from a basketball game in Nogales, Mexico, when he was hit by a bullet fired by an agent on the Arizona side of the border.

According to records released last month, only 13 out of 809 abuse complaints sent to Customs and Border Protection’s office of internal affairs between January 2009 and January 2012 led to disciplinary action, and last week, the agency’s head of internal affairs was removed from his post.

A Customs and Border Protection spokesman declined to comment Wednesday when reached by the Los Angeles Times.

The agency also handcuffed agents by instituting civil liberties protections for potential targets of investigations at public transit stations or on agricultural land, colloquially known as a “farm and ranch check,” Moran said.

For such checks, Moran said, agents are required to create an “operations plan” and be able to show supervisors some kind of intelligence that connects targets of investigations to potential criminal activity. No longer, he said, can Border Patrol agents simply question random people.

Amid a flood of women and children turning themselves in at the border, agents also criticized administration directives to lend help to neighboring agencies.

The Border Patrol “grew but other agencies didn’t grow,” said Tucson sector Agent Art Del Cueto. “They’ve been butchering our agency to assist other agencies.”

According to Agent Chris Cabrera of the Rio Grande Valley sector in southern Texas, in one hour last week, 80 people, mostly women and children, turned themselves in to the Border Patrol in the Rincon Village area of his sector.

Overall, the agency finds itself holding 500 people in the Rio Grande Valley sector each day, he said, down from 700 people each day last year, when a flood of women and children from Central America overwhelmed the U.S. immigration sector.

Typically, one or two agents are stationed near Rincon Village to get people into a shelter and check them for weapons. Those agents can handle 10 or 15 people at once, Cabrera said. But when scores arrive, the agency must call on other agents to respond.

“You’re leaving large swaths of the area unprotected,” Cabrera said. “You take a few agents from the field, then you take a few more, and before you know it, you’re down to five agents covering a 53-mile stretch of river.”

Agents criticized the Border Patrol as top-heavy, with a ratio of four or five agents per each supervisor, a ratio that the agents said should be closer to 10 agents per supervisor.

Cabrera said the issue isn’t a lack of resources, but the way in which they’re used.

“We do not have what we need,” he said, “to do the job we need done.”

Follow @nigelduara on Twitter.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.