ICYMI: Here’s why raising the retirement age is a terrible idea

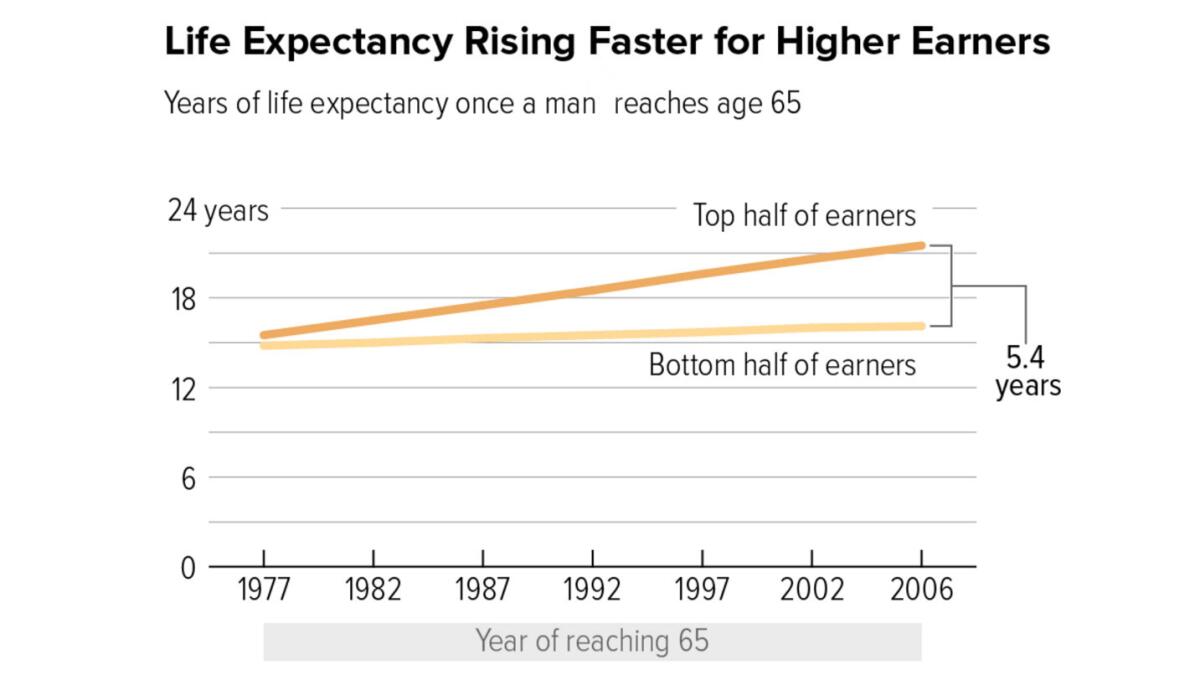

The correlation between life expectancy and income is one of the best-established metrics in American demographics, but seldom is it portrayed as strikingly as in the graphic above, published this weekend by the Health Inequality Project and drawn from a study in the Journal of the American Medical Assn. The chart shows a 15-year gap in life expectancy between the richest and poorest men, and a 10-year gap between the richest and poorest women.

The JAMA paper attributes much of the disparity to higher rates of smoking and obesity, and lower rates of exercise, among poorer Americans. Its authors say they found that access to healthcare and insurance, as measured by the uninsurance rate and Medicare spending, were "not significantly associated with life expectancy for individuals" in the bottom 25% of the income range. But they also acknowledge that the difference in longevity is often "attributed to factors such as inequality, economic and social stress, and differences in access to medical care," and the jury is still out on these theories. Higher rates of smoking and obesity could be artifacts of lack of healthcare services, for instance.

Last January, we explored the implications of this disparity for Social Security, particularly given the popular idea among Republican politicians to raise the retirement age as a solution to its supposed fiscal problems. As the chart shows, that's merely a pathway for the rich to become richer and the poor poorer. We reproduce our original Jan. 25 column below.

----------

As part of its effort to keep the public apprised of the facts underlying policy prescriptions, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities has issued a new primer deconstructing one of the oft-heard ideas to improve Social Security's finances: raise the retirement age.

The brief by CBPP senior policy analyst Kathleen Romig makes clear that this change would be a stealth benefit cut for lower-income workers, wrecking Social Security's progressive benefit structure.

Richer people live longer -- and the gap is growing.

— --Kathleen Romig, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

Superficially, this "fix" seems painless, at least in the form it's generally offered by proponents. The age can be raised gradually and the near-retired (say those now 55 or older) can be exempted. The argument is that older Americans are healthier than ever and working longer, so raising the retirement age may not merely be justifiable, but essential to protect this all-important retirement program.

Plus, there's a precedent. The 1983 bipartisan Social Security reforms raised the normal retirement age, at which full benefits can be collected, from its traditional 65 to 66 for those born in 1943 to 1954, and 67 for those born in 1960 or later.

On the campaign trail, a higher retirement age has been endorsed in one form or another by Jeb Bush, Chris Christie, Marco Rubio, Ben Carson and Ted Cruz, all Republicans. One notable holdout is Donald Trump. Neither of the leading Democratic candidates, Hillary Clinton or Bernie Sanders, favors the idea.

But the proposal has all the flaws of a blunderbuss approach to an issue that cries out for painstaking care. The basic problem with raising the retirement age for Americans is that all Americans are not alike. The differences in life expectancy are closely tied to economic status, education and race.

Indeed, the divergence in longevity between America's richest and poorest workers is widening. "Richer people live longer — and the gap is growing," Romig observes. "Higher-earning men can expect to outlive lower-earning men by more than five years." This gap was almost nonexistent as recently as the late 1970s. (See graph below.)

To put it another way, as did a study released last year by the National Academy of Sciences, among men born in 1930 who reached the age of 50, those in the top 20% of household income had a 45% chance of living to 85, while those in the lowest 20% had only a 27% chance. Thirty years later — that is, for men born in 1960 and therefore turning 56 this year — the chances of living to 85 after reaching 50 had risen to 66% for those in the top 20% of income, while for those at the bottom, the probability had barely budged.

More disturbingly, the life expectancy of some Americans, especially women in the bottom 40% of household income, have been noticeably shrinking. The National Academy of Sciences found that women in that economic group born in 1930 who reached the age of 50 had a roughly 44% chance of living to 85; those born 30 years later had only a 35% chance. For women at the top of the household income scale, however, the chance of living to 85 rose from 60% to 77%.

The implications of this trend for Social Security are inescapable. Through its benefit structure, which provides lower-income workers with a higher benefit proportional to their earnings than it gives higher-income workers, Social Security redistributes wealth from rich to poor. That's fairly well understood. What's less well understood is that it also redistributes from those who die young to those who die older, since the latter collect benefits for a longer period.

The authors of the National Academy study, who included such retirement sages as Peter Orszag and William Gale, pointed out that Americans have tended not to see the latter inequity as unfair because it's "not predictable" — some people will live long, others will die young, "but mostly we do not know which people are which."

But that's changing. The developing trend gives us a better idea of which people are which — and those reaping the benefits are those who already are heavily advantaged in our society. The trend in life expectancy, the authors assert, could "undo much of the redistribution embedded in the benefits formula" that gives lower-income workers a better stipend in retirement.

This implication is simply ignored by those who declare that raising the retirement age is a simple fix for Social Security. It's just the opposite — it's an erosion of the program that works exactly counter to the goals it should be serving.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.