Astronomers’ findings point to a ninth planet, and it’s not Pluto

The scientist who killed Pluto says there may be nine planets in the solar system after all.

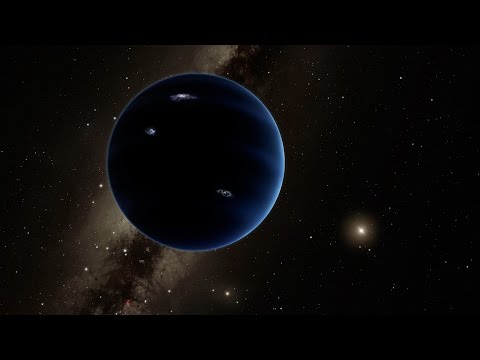

Caltech astronomer Mike Brown and his astrophysicist colleague Konstantin Batygin say they’ve found compelling evidence that a giant planet orbits the sun in the dark, distant badlands far beyond Neptune.

This so-called Planet Nine, described Wednesday in the Astronomical Journal, is about 10 times more massive than Earth and takes 10,000 to 20,000 Earth years to circle the sun, according to their calculations. For the sake of comparison, Neptune makes its round trip in 165 years.

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

If its existence is confirmed by powerful telescopes on Earth, Planet Nine would rewrite our definition of the solar system and help solve some mysteries about its violent past.

“In more than 150 years, we have the first observational evidence that the planetary census of the solar system is incomplete,” said Batygin, the study’s lead author. “We’re truly living in a special time.”

Scientists have long wondered whether a “Planet X” exists in the dim regions far beyond the gas giants Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, which led to Pluto’s discovery in 1930. Their musings took on a new tone in March 2014, when a pair of astronomers announced that they’d discovered a brand-new dwarf planet. The body, known as 2012 VP113, lies in a region beyond the Kuiper belt, a giant ring of icy and rocky debris whose most famous resident is Pluto.

It wasn’t the only such object: Sedna, an icy 600-mile-wide rock discovered in 2003, also boasted this far-out orbit, and it seemed to be making its closest approach to the sun at a similar angle as 2012 VP113. This could be a coincidence — or it could mean that a giant planet was lurking out there in the dark, influencing both their movements.

Brown was intrigued. An expert on the far reaches of the solar system, his 2005 discovery of the dwarf planet Eris forced planetary scientists to reconsider Pluto’s status. Known for decades as the ninth planet in the solar system, Pluto has since been reclassified as a dwarf planet.

After reading up on 2012 VP113, Brown went down the hall to see Batygin, who studies the evolution of the solar system.

“I walked in and said, ‘Look, this is real; we have to figure out what is going on,’” Brown said.

Batygin hadn’t been thinking much about invisible planets in the solar system, but the data on Sedna and 2012 VP113 were intriguing.

The two bodies “are really outliers,” Batygin said. “Their orbits do not hug the orbit of Neptune, and hugging the orbit of Neptune is kind of a unifying feature among the vast population of Kuiper belt objects.”

So how did they get there? Neptune could not have been responsible, since it was too far away, Batygin said.

Batygin and Brown considered other explanations. They studied the paths of half a dozen distant objects in the solar system, in the hopes that the shapes of their orbits would reveal the gravitational fingerprint of a hidden planet.

They began to see a strange pattern: Compared with the orbital plane of Earth and the other planets, all of these objects’ orbits were tilted downward, and at about the same angle. Also, their orbits — including their perihelia, the points at which each object came closest to the sun — were clustered fairly close together, rather than being randomly distributed.

Brown was baffled by these orbits, which often crossed one another. There’s no way these overlapping paths should remain stable, he thought — unless there was something else out there that was massive enough to shepherd these objects along their mysterious tracks.

Using sophisticated computer simulations, the scientists calculated that there’s only a 0.007% possibility that these tightly clustered orbits arose by chance.

“We would have to get monstrously lucky to have the solar system that we have,” Batygin said.

The more he and Brown crunched the numbers, the more convinced they became that a massive planet was not just possible but likely.

The scientists calculated that the planet would have a long, elliptical orbit whose closest approach to the sun was on the opposite side of the objects it was shepherding. But even at its nearest, it was still 200 astronomical units, or Earth-sun distances, away. At its farthest, it might be 600 or 1,200 astronomical units from the sun. (Neptune, by contrast, is about 30 astronomical units from the sun, and the outer edge of the Kuiper belt is 50 astronomical units away.)

The computer simulation neatly explained the orbits of Sedna and 2012 VP113. But the true power of their prediction was that it described the behavior of other objects that the scientists did not set out to explain.

The model showed that there must be a weird class of objects that move perpendicular to the planetary plane. At first, this seemed patently ridiculous to the researchers — until they looked it up and found that there were, in fact, several known objects moving in a manner that matched their calculations.

“That’s when my jaw hit the floor,” Brown said.

Though 10 times more massive than Earth, Planet Nine would be tiny compared with the solar system’s gas giants, Brown and Batygin said.

In fact, this may be why it’s been banished to the interplanetary boonies, said Scott Sheppard, an astronomer at the Carnegie Institute for Science in Washington, who was not involved in the new study. Planet Nine may have formed closer to the sun but was hurled out of the area thanks to the gravitational influence of Jupiter or Saturn.

“It was probably the runt of the family,” said Sheppard, who co-wrote the paper that originally piqued Brown’s interest.

Planet Nine, if discovered where it’s predicted to be, would follow recent astronomical tradition. The last and most distant planet discovered in our solar system, Neptune, was found thanks to the mathematical predictions of Frenchman Urbain Le Verrier in 1846; German astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle spotted it within a day of receiving Le Verrier’s calculations.

Finding this new distant world, however, probably will be much harder than finding Neptune. At its closest point to Earth, it would be roughly 18.6 billion miles away, where little sunlight can reach. It will take powerful telescopes such as the Keck Observatory and Japan’s Subaru Telescope, both on Mauna Kea in Hawaii, to find Planet Nine, if it’s really out there.

In some ways, the scientists noted, it might be easier to see planets around other, far more distant stars, simply because you know where to look — directly at the star as a planet transits in front of it. In the case of Planet Nine, the researchers don’t know exactly where it lies in its potentially 20,000-year-long orbit — which means there’s a lot of celestial ground to cover.

Sheppard said his certainty that Planet Nine exists has now risen from about 50% to 60%. Now he’s searching for more small objects whose orbits may bear the mark of Planet Nine in the hopes that it will help others figure out where the mysterious world might be.

If they determine that Planet Nine exists, it could shed light on the solar system’s tumultuous early years and help explain why the solar system looks the way it does today, scientists said.

For instance, it could help account for the unusual demographics of our solar system, which looks quite different from the systems around other stars observed by NASA’s Kepler space telescope.

Kepler has found that planets of a few to several Earth masses — super-Earths and mini-Neptunes — are common around other stars. Yet our solar system seems to be missing these usual characters.

If Planet Nine is real, Brown said, then our home in the galaxy doesn’t look quite so different after all.

Confirmation might also rehabilitate Brown’s image as the “Pluto killer.”

“I hope so,” he said. “My daughter is the one who told me I need to do this. Even before we started this, she said, ‘Daddy, what you need to do is go find a new planet so that people will no longer be sad about Pluto.’”

Twitter: @aminawrite

Follow @aminawrite on Twitter for more science news and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE SCIENCE NEWS:

2015 was the hottest year on record, according to new data

Toxins from algal blooms may cause Alzheimer’s-like brain changes

Say cheese for science: Camera traps show how habitat protection aids biodiversity