Donors to state tax board candidates bypass contribution limits

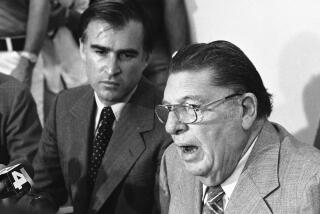

Two days after California’s elected tax board gave SpaceX exemptions worth millions of dollars last year, the Hawthorne rocket company donated $7,500, at the request of board President Jerome Horton, to a nonprofit group founded by his wife.

SpaceX made the donation as a sponsor of a public conference headlined by Horton as he was running for reelection.

Such donations are among the ways that businesses and others with matters before the state Board of Equalization have benefited its members despite a tough law passed in 1990 to prevent conflicts of interest, a Times analysis shows.

Other ways to bypass the contribution caps include giving through political action committees, donating just below the legal limit and contributing to board members’ outside projects.

The law is “subject to a lot of game-playing,” said Lenny Goldberg, executive director of the California Tax Reform Assn. “It’s not very effective.”

California’s five-member Board of Equalization is the only elected tax commission in the nation. It collects sales, property and use taxes, acts as the state’s tax court in settling disputes, and assesses public utility and railroad properties. It takes in about $60 billion for the state each year.

Four board members are elected by districts; the state controller is the fifth member. The Times reviewed campaign finance and gift reports filed by current members covering the six years since Horton took office.

With the financial stakes so high in the board’s quasi-judicial decisions, the Legislature and governor acted a quarter of a century ago to implement special rules for the panel to prevent corruption.

The law requires members to recuse themselves or return contributions before voting on matters affecting companies that have given them $250 or more in the preceding 12 months.

On May 19 last year, shortly before California’s statewide primary election, 25 executives, attorneys and other employees of the tax consulting firm Ryan LLC each gave $249 to the campaign of board Vice President George Runner, a Republican from Lancaster.

Because the donations were a dollar short of the limit, Runner was free to vote the following year in any matter involving the company or its employees.

The firm’s workers contributed similarly to Horton, a Democrat who received 45 campaign contributions of $249 each from them for last year’s election. Other board members also received some small contributions but not large batches from employees of one business.

“There are so many ways to circumvent the Quentin Kopp Act,” Horton acknowledged, referring to the conflict-of-interest law, named for the former Bay Area lawmaker who wrote it.

Representatives of Ryan, which has clients with business before the tax board periodically, declined to comment.

Board members say they have complied with the law and will continue to do so.

Horton said that in the future he would return any contribution that would prohibit him from voting on an issue.

The Ryan firm has not appeared before the board in the last year, officials said. If representatives or employees of the company were to appear within a year of multiple $249 contributions to him, Runner said, he could legally vote but would weigh the circumstances and determine whether there was an “appearance of a conflict” that might cause him to return the money.

Other big firms with business before the board typically circumvent the $250 limit by donating larger amounts to a group called the Taxpayers Political Action Committee (TaxPAC), a business group funded by utilities and other firms with business before the group , including AT&T and Southern California Edison.

Candidates can accept up to $13,600 from the committee in an election year, but there is no limit on how much the committee may spend independently on mail, ads and other methods of supporting a contender for office.

Runner’s and Horton’s campaigns have received $39,000 and $26,000, respectively, from TaxPAC since they first ran for the board, campaign filings with the government show. The committee spent $50,000 on an independent campaign in support of Runner last year.

The PAC also has contributed thousands of dollars to Republican Board member Diane Harkey of Dana Point, Democratic Board member Fiona Ma and Democratic state Controller Betty Yee, who also sits on the board.

Today Kopp, a former state senator, says board members should be banned from taking any money from groups that appear before them.

“That is a loophole that needs to be closed,” said Kopp, a retired Superior Court judge. “I think it should be zero.”

That would be fine, Runner said.

“That wouldn’t be an issue for me. I just don’t like the presumption that $249 creates a biased response,” he said.

Horton also said campaign contributions have no effect on how he votes.

“Does it influence me?” he said. “Not at all.”

Yee, previously elected to the board and a member since 2004, said she would support subjecting political action committees to the $250 contribution limit.

“It would just make everything a little bit clearer — that the rules are the same across the board,” she said.

Yee also said she would support a prohibition against board members keeping any contributions from those appearing before the panel. In addition, she voiced concern about gifts.

Last year, during his reelection campaign, Horton asked companies to contribute a combined $200,000 to a nonprofit called California Educational Solutions. The group used much of the money to stage its annual conference, Connecting Women to Power, at Cal State Dominguez Hills, attracting 2,500 attendees.

The invitations prominently listed Horton as host.

Horton’s wife, Inglewood City Clerk Yvonne Horton, was president and chief executive of California Educational Solutions until April 25, 2014. Since then, she has been a volunteer president emeritus, her husband said.

She was still president when her husband asked AT&T, Southern California Edison and other firms to contribute to the nonprofit last year, according to corporation records filed with the state.

SpaceX, headed by Elon Musk, a Los Angeles entrepreneur, gave the group $7,500 less than one month after she stepped down as president in April. Yvonne Horton continued to organize her husband’s conference, which listed Musk’s firm as a sponsor.

Horton solicited the donation, according to records filed with the state Fair Political Practices Commission. The donation was made two days after the Board of Equalization approved a policy that provides a tax exemption for property including rocket parts involved in the space flight industry. The firm, formally known as Space Exploration Technologies Corp., has developed rockets for commercial uses that include serving the International Space Station.

Jerome Horton said there was no link between his vote on the tax policy and his request that SpaceX give to the nonprofit.

SpaceX made a similar disclaimer.

“There is absolutely no link between this donation and the board’s actions,” said John Taylor, a spokesman for SpaceX, who noted the company also made donations in 2013 and 2015.

Horton said he and his wife received no income from the nonprofit and that the conference helps women get ahead financially.

“Promoting worthy community activities is always good for one’s image,” he said. But help in an election year, he said, “certainly wasn’t the objective.”

Twitter: @mcgreevy99

ALSO

Photo of dog’s taped muzzle sets off Web frenzy; police investigating

Sheriff’s Dept. investigating reports that deputy sexually abused female inmates

Suspect in deadly Planned Parenthood attack said ‘no more baby parts,’ official says

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.