Rondal Partridge dies at 97; photographer known for irreverence

Rondal Partridge apprenticed himself to Ansel Adams as a teenager, lugging the master photographer’s heavy equipment up and down Yosemite’s majestic peaks.

He also was fired on several occasions, including the time he tied Adams’ shoelaces together and made him fall on his face.

Such irreverence became a hallmark of Partridge’s work.

Like Adams, Partridge photographed many of the West’s natural wonders. But unlike his mentor, he worked to show humanity’s encroachments — power lines marring a vista, tire tracks crisscrossing a pristine beach and parked cars clogging the foot of Yosemite’s grand Half Dome.

Adams “always jumped over the fence … walked past the garbage. He always wanted to get an immaculate view,” his student once said, “and I spent my life stepping back to include the garbage in my photographic view.”

Partridge, one of the last links to a defining era in Western photography who learned not only from Adams but also from Dorothea Lange and his mother, Imogen Cunningham, died of natural causes June 19 in Berkeley. He was 97.

“We used to call him the last man standing,” said his daughter Elizabeth Partridge, who confirmed his death. “He was the last of the people who got all this great tutoring from these incredible photographers, then spent his life doing it.”

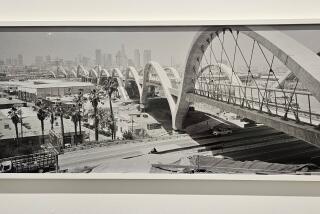

During a career that spanned more than six decades, Partridge ranged widely for his subjects. Much of his work chronicles the development of freeways and suburbs. During the 1950s and ‘60s, he was a photographer for prominent Modernist architects, including Thomas Church and John Carl Warnecke.

But he also was drawn to portraiture, producing intimate studies of friends, family, rodeo cowboys, migrant workers and Navy officers. He made still lifes of plants, often chronicling their decay.

“He was formed by that classic generation of California photographers who prized and celebrated nature,” said Sally Stein, a retired historian of photography at UC Irvine, who collaborated with Elizabeth Partridge on “Quizzical Eye: Photography of Rondal Partridge” (2003). “At the same time, he was commenting on it and … saying if you’re going to talk about nature you’ve got to see nature in all its phases.”

His best-known photograph, taken in 1965, was the view of Half Dome, the Yosemite landmark, spoiled by row upon row of parked cars. He called it “Pave It and Paint It Green.”

Adams “idealized everything.… He photographed purity,” Partridge said in the San Francisco Chronicle in 2003, when the Oakland Museum of California and the California Historical Society in San Francisco each mounted shows of Partridge’s photography. “I made fun of the virginal purity that he insisted on.”

Partridge was born in San Francisco on Sept. 4, 1917, and grew up in a bohemian world. His father, Roi Partridge, was an accomplished etcher who taught at Mills College. His mother, Cunningham, was a photographer and free spirit known for her portraits of artists, botanical studies and nudes. She also was a founding member of Group f/64, the influential collective that included Adams, Lange and Edward Weston and pushed for greater realism in photography.

Rondal was 5 when he began helping Cunningham in the darkroom and was attending high school in Oakland when he began joining her on photo shoots.

“My mother taught me to be alert and aware — to photograph anything,” he told the Fresno Bee in 2006.

When Rondal was 17, his parents divorced and he began his apprenticeships.

Lange paid him $1 a week to be her darkroom assistant and driver across miles of Central California’s back roads, where she documented lives worn thin by the Depression. He considered her a more influential teacher than Adams and took one of his most memorable portraits at a migrant camp like those he visited with her. Shot in Kern County in 1940, it shows a young woman in a sunbonnet and work clothes, striking a saucy pose. Partridge called her “Potato Field Madonna.”

Partridge took that photo when he was working for the National Youth Administration, a New Deal jobs program for young Americans. He later worked as a photojournalist for the Black Star agency in New York and served as a photographer in Navy intelligence during World War II.

His wife of 68 years, the former Elizabeth Woolpert, died in 2009. He is survived by their five children, Joan, Josh, Elizabeth, Margaret and Aaron; three grandchildren and a great-grandchild.

He never grew rich off his photographs and cared little about recognition. “He was almost allergic to the whole art world scene,” Elizabeth Partridge said, “sometimes to his own detriment.”

In his last years, he devoted himself to mastering hand-coated platinum printing, a challenging process used by his mother that produces archival quality prints. He focused on images of plants, antique tools and dead animals.

“I don’t want the money. I don’t need the fame. I don’t need the admiration. I’d like all of those things, but I don’t need them,” he once said. “Because what I get from photographing is learning. I have spent my life learning by looking through a lens.”

Twitter: @ewooLATimes

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.