NASA’s Messenger crashes into Mercury: Scientists mourn

It’s official: NASA’s Messenger spacecraft has ended its mission to Mercury with a smashing grand finale.

The spacecraft wrapped up its four years in orbit by crashing into the tiny planet’s surface around 12:26 p.m. Pacific time Thursday, officials confirmed. That time and the impact’s location are a best guess because Messenger crashed on the far side of Mercury, with no way to phone home.

Had it not crashed, Messenger would have come back into contact around 12:40 p.m. Pacific, and the Deep Space Network station in Goldstone, Calif., would have picked up a signal. But no signal came.

“On behalf of MESSENGER, thank you all for your support,” officials tweeted from the mission’s Twitter account. “We will continue to update you on our great discoveries. We will miss it.”

Even though the spacecraft met its end alone, scientists in the mission control room at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland said they mourned the passing of the spacecraft, whose observations have significantly altered our understanding of the sun-scorched little planet.

“I think everybody has mixed feelings,” Messenger’s lead scientist, Sean Solomon, who is director of Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, said in an interview shortly before the crash. “Everybody is proud of the many accomplishments of the Messenger mission ... at the same time, there’s this impending sense of loss.”

In some ways, it was like losing a family member, said Solomon, who called the spacecraft an “almost animate object that has become very known and dear to us.”

Messenger, launched in August 2004, was the first spacecraft to ever orbit Mercury, the smallest planet in the solar system and the closest to the sun. Maintaining orbit around a planet so close to its home star was an engineering feat -- the spacecraft needed to withstand damaging solar radiation as well as resist the sun’s powerful gravitational tug. At launch, more than half of the spacecraft’s mass was fuel.

But with its fuel reserves finally exhausted, Messenger had no other options but to crash, scientists said.

The spacecraft has done exemplary work, Solomon said. Among its many discoveries: that even though Mercury sits searingly close to the sun, it holds reserves of water ice and organic matter in permanently shadowed regions at its poles; that a surprising amount of light, volatile elements still remain on the planet; and that the planet has dropped a dress size or two, shrinking nearly 9 miles in diameter over the last 4 billion years or so.

“That speaks to the processes by which the building blocks of the inner planets came together to form the planets we see today,” Solomon said. “Each of the planets had an important chapter to tell us in the history [of the solar system], and the challenge is to make sense of it.”

Before Messenger’s literal deadline, the scientists worked to pull all the data that they could from the spacecraft, prioritizing certain bits over others. Messenger was able to transmit only so much data before disappearing behind Mercury, and so a portion of lower-priority information inevitably went down with the spacecraft.

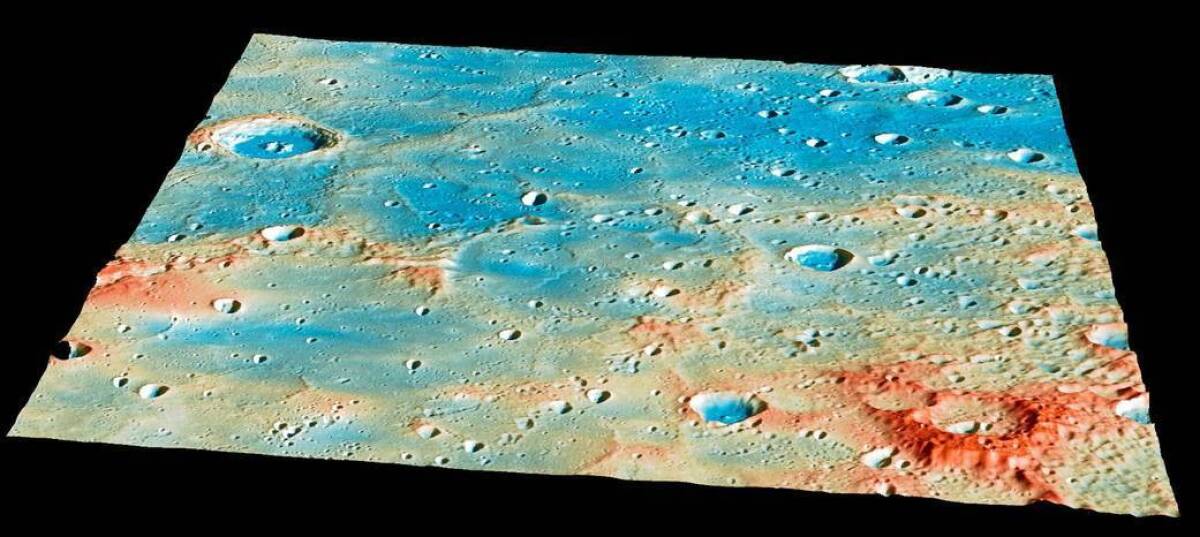

Meanwhile, mission officials have identified the patch of land that probably holds the spacecraft’s final resting place. Messenger sped toward Mercury at more than 8,700 miles per hour, carving a roughly 52-foot-wide crater into its surface.

Even in death, the spacecraft will generate more scientific data: That crater’s properties, and how its appearance changes over time, can be studied by future missions, Solomon said.

“It would be nice if the end of Messenger were actually the beginning of experiments that told us something about how the surface of Mercury got darker over time,” he added.

Follow @aminawrite for more interplanetary science news.