Reading in the material world

If you’re a digital immigrant as I am, there’s something deeply satisfying about Michael S. Rosenwald’s report in the Washington Post that “millennials still strongly prefer print for pleasure and learning, a bias that surprises reading experts given the same group’s proclivity to consume most other content digitally.”

The reasons: Stillness, lack of distraction, the ability to concentrate and the understanding that memory relies on, among other things, physical cues.

Same, in other words, as it ever was.

I won’t lie: I have a dog in this fight, or at least a vested interest. I’ve never believed digital reading would supplant print. Enhance, yes, increase the audience, make books more widely available. For me, though, they remain two very different experiences, the former about culling information, the latter about immersion, flow.

When I read on-screen, it is always with an eye (or part of one) on what’s outside the text — email, Internet, social media. I take breaks, check Facebook, resist, in some essential sense, the pull of narrative.

On the page, however, I give over much more fully. I read, generally, in bed, in a room with no electronics; I do not want to be disturbed. Environment, then, is an essential factor — both the environment of the book, and the environment in which I read. I want the experience to be unbroken, to find myself by losing myself.

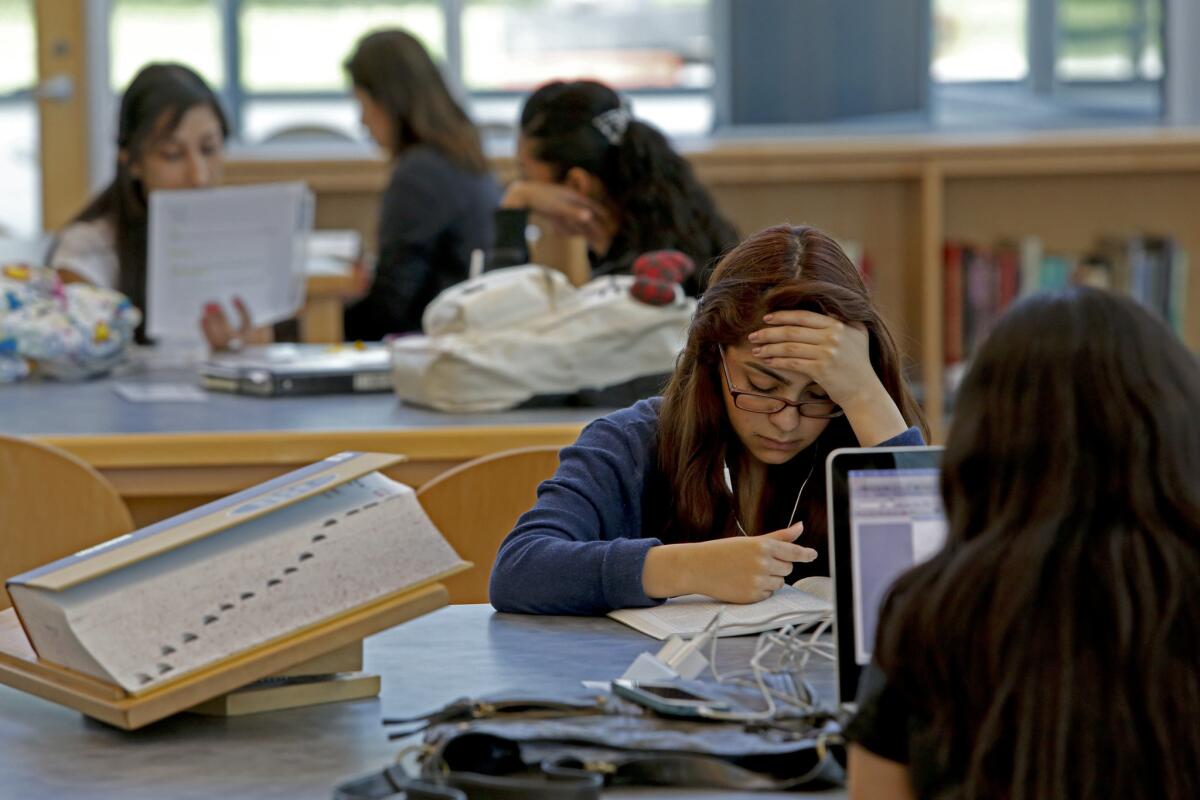

Rosenwald’s piece tracks a similar set of intentions, albeit among a population we tend not to consider in such terms. He cites a Pew study finding that “the highest print readership rates are among those ages 18 to 29, and the same age group is still using public libraries in large numbers,” and quotes a student who says approvingly of print, “It takes me longer because I read more carefully.”

What he’s getting at is slow reading, which makes sense as a counter-reaction to a culture of constant stimulation, constant response. How can we think when we are always talking, tweeting, surfing, looking around for bits and pieces of reaction rather than a more integrated point-of-view?

Reading, on the other hand, is — or can be — a slow process, a dialogue, a conversation; the engagement is the point.

Some of my most vivid moments of connection have been stirred by reading — moments that have required my attention, my focus and my heart. I think of Nick Carroway, of Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarty, of Pip and Dostoevsky’s Underground Man. I think of James Baldwin, recalling his rage at his dead father in “Notes of a Native Son,” or Lorrie Moore, in the story “Referential,” describing a mother’s longing for her troubled son.

I’m not saying that can’t happen with an e-book, just that reading reminds us of a world, a universe, beyond us, in which we inhabit the landscape of an imagination not our own.

Print encourages this because of its physicality; the book is an object we must open up and climb inside. Screens, on the other hand, feel more confirming of our expectations, our outsourced memories: How many photos do you have on your smartphone?

What I mean is that on a device such as an iPad or an iPhone, we never lose sight of ourselves — they are customized environments, extensions of our psyches — whereas the print book exists in a different realm. It requires an externalized commitment, an accommodation, in which its otherness is part of the point.

This is not to suggest that there are no charms to the digital, with its speed, its connectivity — just that this is not always what we look for when we read.

Which is why I remain encouraged by the notion that, as Don Kilburn of the educational publisher Pearson tells Rosenwald, the digital revolution “doesn’t look like a revolution right now. It looks like an evolution, and it’s lumpy at best.”

Twitter: @davidulin

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.